What better way to remember the horrific Jallianwala Bagh massacre on its centenary than to edit a book that collects, translates and reflects on some of the literature published on the topic?

That’s exactly what author Rakshanda Jalil did.

Jalil is a renowned literary historian based in Delhi, who has previously written about the literature produced about the Indian Partition and the First World War.

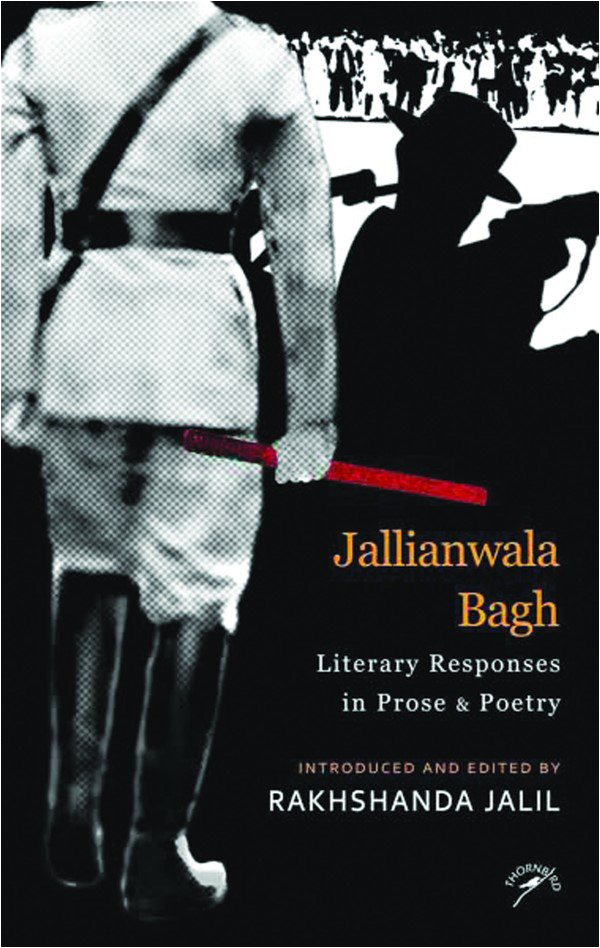

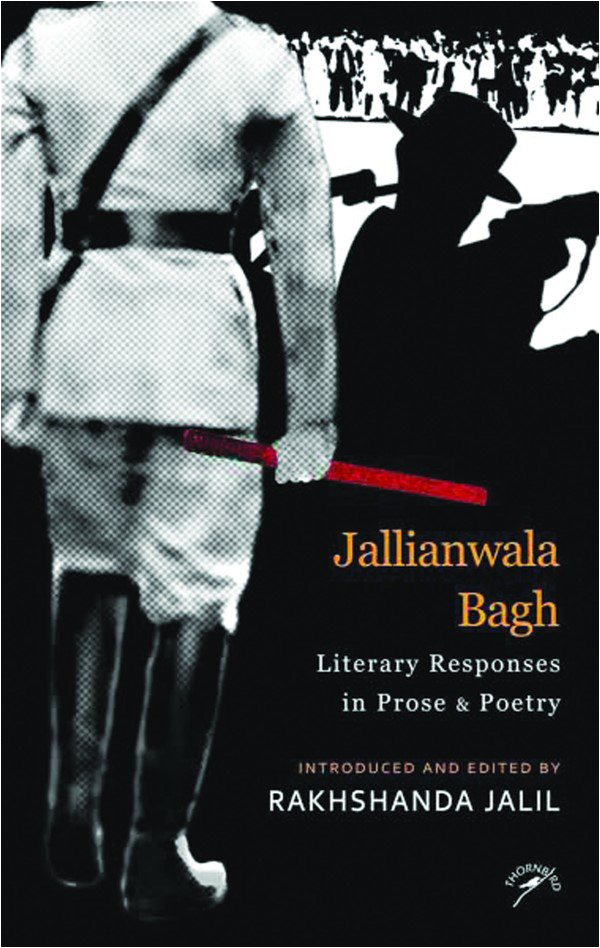

Her latest effort is titled Jallianwala Bagh: Literary Responses in Prose & Poetry. It has been released by Niyogi publishers recently and is available on Kindle now.

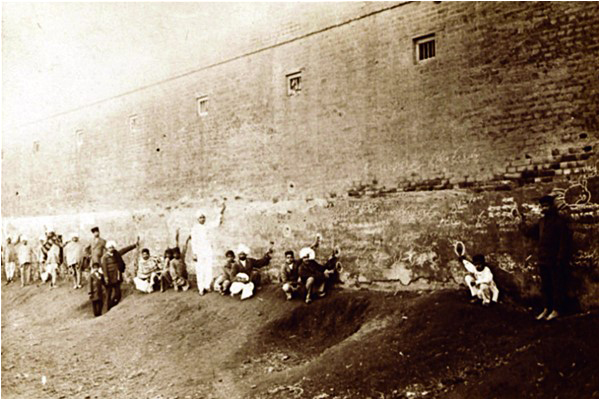

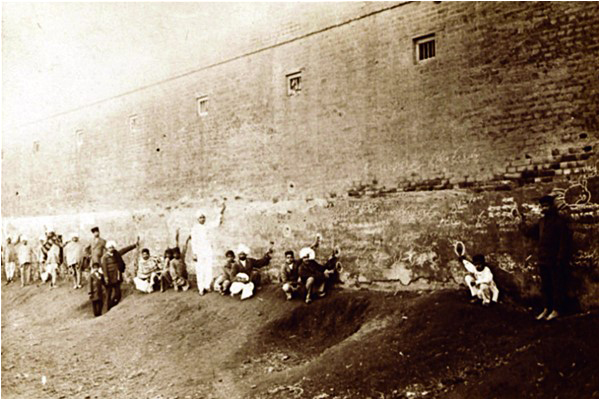

The Jalliawala Bagh massacre took place on the 13th of April in 1919 when the British Indian Army fired on unarmed civilians peacefully protesting against the arrest of Satya Pal and Saifuddin Kitchlew, who had been protesting against the implementation of the the Rowlatt Act in Punjab.

Jalil says she first became interested in the Jallianwala Bagh when she was writing her book on the literary response to the First World War in the Indian Subcontinent. She describes it as a natural progression from one topic to another.

“1.3 million people went to fight in the First World War and 74,000 of them died,” she says. “A great majority of them were Punjabis. The people of Punjab begin to think that they had given such great sacrifices and now they wanted just a few reforms. But instead they got the draconian Rowlatt Act and protests were met with a barbaric reply. The people there developed this sense of victimization while there was, in any case, a lot of dissent in Punjab before 1919.”

She adds that the British misread this protest as active resistance and expected it to turn into an 1857-like rebellion.

The Rowlatt Act was passed on the 10th of March 1919 by the Imperial Legislative Council in Delhi.

The Act extended the emergency measures of preventive detention indefinitely, making incarceration without trial and judicial review possible for up to two years. It was enacted as a result of the perceived threat from revolutionary nationalists. Stricter control of the press and public gatherings was possible now along with a juryless “in camera trials”. Several restrictions were applied on political prisoners accused or convicted under the Act, including a ban on any religious or political activity from that point on. This act was widely criticized by Indian leaders including Gandhi.

“The response from Punjab was immediate - like it was hit on the knee,” says Jalil. “There is a sense of betrayal. The people feel that they gave so much to the British so why was their loyalty questioned? The time before Jallianwala Bagh was the epitome of Hindu-Muslim unity in Punjab and different authors have commented on this in various ways. The streets had chants of “Hindu-Musalman ki Jai!” There is a pluralism in the air. The people who die in the massacre include all the major communities who were there to see the Vaisakhi Mela. They were from the villages, common farmers and workers, who were not there for a political gathering but rather a cultural event.”

The works of authors like Saadat Hasan Manto, Abdullah Hussain, Krishan Chander, Ghulam Abbas, Chaman Lal, Mulk Raj Anand, Navtej Singh; and poets like Zafar Ali Khan, Sohan Singh Misha, Josh Malihabadi and Nanak Singh among others have been included in the anthology.

What surprised her the most while researching these works?

“I think I discovered a sharp political sense coming out in poetry and in literature,” she says. “Poets like Hasrat Mohani who indulged in romantic poetry gained a political consciousness with this event. Urdu poets, who we believe always talk of love, they are now moving beyond love to the political landscape of their country. I discovered a political consciousness, particularly in Urdu poetry.”

But she also discovered humor which authors like Ghulam Abbas used in stories like “Those Who Crawled” – a hilarious anecdote of two young men who defy the curfew by crawling on their bellies and telling an agitated officer that they are in a race to reach the line first.

“The politically aware author uses satire to oppose this dictatorship,” she says.

The book has 11 works of fiction, including a play. The poetry section is separate.

The non-fiction response to the massacre has not been included because the editor wanted to focus on the creative writer’s imaginative reaction. Many of the works have been translated from Urdu, Punjabi, and even Marathi.

Navtej Singh calls the Jallianwala Bagh massacre a “metaphor of injustice” and says it is thriving in him as a political moment even today. Whenever he sees any cruelty in the world, it reminds him that Jallianwala Bagh is alive. This great tragedy is, therefore, talking to us across time.

“The number of people who died, 1,500 or so, the different estimates are not the only about this tragedy,” says Jalil. “What were the consequences of this tragedy? Far-reaching.”

Jalil adds that a Maharashtrian author, Venu Chitale, pens her story in Pune, which is very far from Amritsar. “In a time where there were no telephones and even telegrams were rare, the newspapers were the main source of news. How did the news of this tragedy reach every nook and corner of India? What impact did it have on people and how did creative writers interpret it? How did a woman writer in Pune weave it into her own narrative?

Some of these authors wrote about Jallianwala Bagh before the 1947 Partition and some long after the blood had dried. Sarojini Naidu and Rabindranath Tagore responded within days of the disaster.

Jalil mentions Ratan Devi, who has a plaque in Jallianwala Bagh and Bhishan Sahni mentions her in his play. She is repeatedly mentioned though. She was a widow who defied the curfew and protected the body of her deceased husband from the scavengers with a stick. The locals were prohibited from burying or approaching the bodies. Eventually, she refused compensation from the Indian government and became a defiant heroine. “The point of art and literature is that it fleshes out a bland character and gives us a backstory. Now Ratan Devi is a living woman who has been given a new life through literature. We can now see her celebrating Vaisakhi and performing kikli with her friends.”

The book is a literary gem that is full of pleasant surprises and breathes some fresh air into the otherwise deeply traumatic event that brought unprecedented anguish to the Subcontinent.

“Every tragedy has lessons and that is why we call it a tragedy.” she points out.

The writer is based in Lahore. She tweets as @ammarawrites and her works are available on www.ammaraahmad.com

That’s exactly what author Rakshanda Jalil did.

Jalil is a renowned literary historian based in Delhi, who has previously written about the literature produced about the Indian Partition and the First World War.

Her latest effort is titled Jallianwala Bagh: Literary Responses in Prose & Poetry. It has been released by Niyogi publishers recently and is available on Kindle now.

The non-fiction response to the massacre has not been included because the editor wanted to focus on the creative writer’s imaginative reaction

The Jalliawala Bagh massacre took place on the 13th of April in 1919 when the British Indian Army fired on unarmed civilians peacefully protesting against the arrest of Satya Pal and Saifuddin Kitchlew, who had been protesting against the implementation of the the Rowlatt Act in Punjab.

Jalil says she first became interested in the Jallianwala Bagh when she was writing her book on the literary response to the First World War in the Indian Subcontinent. She describes it as a natural progression from one topic to another.

“1.3 million people went to fight in the First World War and 74,000 of them died,” she says. “A great majority of them were Punjabis. The people of Punjab begin to think that they had given such great sacrifices and now they wanted just a few reforms. But instead they got the draconian Rowlatt Act and protests were met with a barbaric reply. The people there developed this sense of victimization while there was, in any case, a lot of dissent in Punjab before 1919.”

She adds that the British misread this protest as active resistance and expected it to turn into an 1857-like rebellion.

The Rowlatt Act was passed on the 10th of March 1919 by the Imperial Legislative Council in Delhi.

The Act extended the emergency measures of preventive detention indefinitely, making incarceration without trial and judicial review possible for up to two years. It was enacted as a result of the perceived threat from revolutionary nationalists. Stricter control of the press and public gatherings was possible now along with a juryless “in camera trials”. Several restrictions were applied on political prisoners accused or convicted under the Act, including a ban on any religious or political activity from that point on. This act was widely criticized by Indian leaders including Gandhi.

“The response from Punjab was immediate - like it was hit on the knee,” says Jalil. “There is a sense of betrayal. The people feel that they gave so much to the British so why was their loyalty questioned? The time before Jallianwala Bagh was the epitome of Hindu-Muslim unity in Punjab and different authors have commented on this in various ways. The streets had chants of “Hindu-Musalman ki Jai!” There is a pluralism in the air. The people who die in the massacre include all the major communities who were there to see the Vaisakhi Mela. They were from the villages, common farmers and workers, who were not there for a political gathering but rather a cultural event.”

The works of authors like Saadat Hasan Manto, Abdullah Hussain, Krishan Chander, Ghulam Abbas, Chaman Lal, Mulk Raj Anand, Navtej Singh; and poets like Zafar Ali Khan, Sohan Singh Misha, Josh Malihabadi and Nanak Singh among others have been included in the anthology.

What surprised her the most while researching these works?

“I think I discovered a sharp political sense coming out in poetry and in literature,” she says. “Poets like Hasrat Mohani who indulged in romantic poetry gained a political consciousness with this event. Urdu poets, who we believe always talk of love, they are now moving beyond love to the political landscape of their country. I discovered a political consciousness, particularly in Urdu poetry.”

But she also discovered humor which authors like Ghulam Abbas used in stories like “Those Who Crawled” – a hilarious anecdote of two young men who defy the curfew by crawling on their bellies and telling an agitated officer that they are in a race to reach the line first.

“The politically aware author uses satire to oppose this dictatorship,” she says.

The book has 11 works of fiction, including a play. The poetry section is separate.

The non-fiction response to the massacre has not been included because the editor wanted to focus on the creative writer’s imaginative reaction. Many of the works have been translated from Urdu, Punjabi, and even Marathi.

Navtej Singh calls the Jallianwala Bagh massacre a “metaphor of injustice” and says it is thriving in him as a political moment even today. Whenever he sees any cruelty in the world, it reminds him that Jallianwala Bagh is alive. This great tragedy is, therefore, talking to us across time.

“The number of people who died, 1,500 or so, the different estimates are not the only about this tragedy,” says Jalil. “What were the consequences of this tragedy? Far-reaching.”

Jalil adds that a Maharashtrian author, Venu Chitale, pens her story in Pune, which is very far from Amritsar. “In a time where there were no telephones and even telegrams were rare, the newspapers were the main source of news. How did the news of this tragedy reach every nook and corner of India? What impact did it have on people and how did creative writers interpret it? How did a woman writer in Pune weave it into her own narrative?

Some of these authors wrote about Jallianwala Bagh before the 1947 Partition and some long after the blood had dried. Sarojini Naidu and Rabindranath Tagore responded within days of the disaster.

Jalil mentions Ratan Devi, who has a plaque in Jallianwala Bagh and Bhishan Sahni mentions her in his play. She is repeatedly mentioned though. She was a widow who defied the curfew and protected the body of her deceased husband from the scavengers with a stick. The locals were prohibited from burying or approaching the bodies. Eventually, she refused compensation from the Indian government and became a defiant heroine. “The point of art and literature is that it fleshes out a bland character and gives us a backstory. Now Ratan Devi is a living woman who has been given a new life through literature. We can now see her celebrating Vaisakhi and performing kikli with her friends.”

The book is a literary gem that is full of pleasant surprises and breathes some fresh air into the otherwise deeply traumatic event that brought unprecedented anguish to the Subcontinent.

“Every tragedy has lessons and that is why we call it a tragedy.” she points out.

The writer is based in Lahore. She tweets as @ammarawrites and her works are available on www.ammaraahmad.com