Project Ghazi has re-released nationwide over 20 months after its initial release. The film that was billed as Pakistan’s first sci-fi movie was retracted after its premiere two years back - owing, apparently, to sound issues.

Humayun Saeed, one of the stars of the film had left the screening 20 minutes into the movie back in July 2017, which is all you needed to know about the initial release. Saeed told media that he did not want viewers to watch the movie in its then existing form, because it was “hard to listen to the dialogues.”

The producers decided rework the 2017 film and felt that all that needed fixing was done as it hit the theatres once again this year.

In 20 months a new film can easily be made – an elaborately-thought-out one at that – which is perhaps what the filmmakers should have gone for, instead of just fixing sound issues, which ostensibly took almost two years.

Given the final product, perhaps the fact that people had a problem hearing what was being said on the screen might not have been that bad a thing for anyone associated with the film – especially their reputations as professionals. In fact, the filmmakers should have perhaps created a few visual problems as well, which would have forced us all to be kind to the film’s “attempt” having not known what exactly to criticize, so as to safeguard the “revival of Pakistani cinema”.

Another, more immediate, benefit of tampering with the film’s visuals would have meant that no one would have had any idea what was going on – which is precisely what one experiences with the visuals, but would then have been spared the optical torture.

The only science in the film is surrounding the fact that the movie has actually consumed money and human resources in order to come into being. And the real fiction lies in Project Ghazi self-identifying as a “film” that is made by those who do this for a living.

What is even more remarkable is that the film does so with a decent enough cast that features Humayun Saeed, Syra Shehroze, Shehryar Munawar and the veteran Talat Hussain.

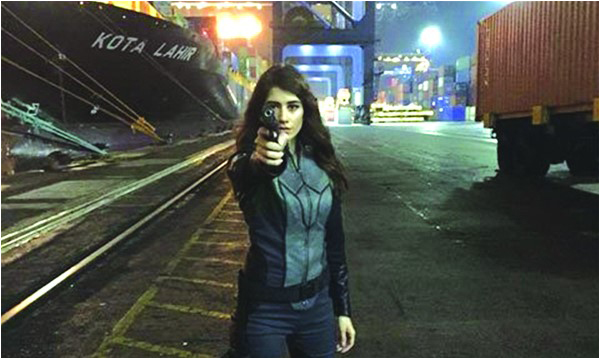

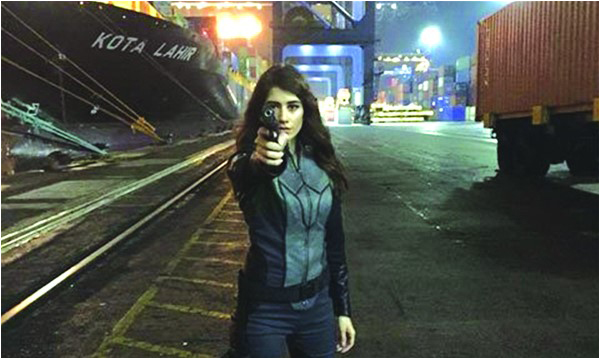

The story revolves around a group of scientists headed by Dr Zaid (Talat Hussain) who tried to develop a new breed of advanced soldiers for Pakistan many years ago. The project was hijacked by some masked man, for reasons perhaps not even known to them. Salaar (Humayun Saeed), Zain (Shehryar Munawar) and Zara (Syra Shehroze) – who are all part of the line of defence without the viewer actually knowing which one does what – try to stop the evil forces, spearheaded by Qatan (Adnan Jaffar).

Acting is a part of the unmitigated shambles that Project Ghazi is, and individually critiquing each case would be as much a waste of our time – just as being a part of the film was a waste of theirs.

If one were forced to pick the worst thing about Project Ghazi it would perhaps be the editing and the action – both are performed with the technological finesse of a roadside butcher.

That someone chose to write the film is something that might need convincing as well. For while the butchery that the editing was results in a haphazard spectacle for the viewer – who can be surprised, shocked and bewildered, depending on how much the ticket cost as a percentage of their monthly income – there clearly is no defined script.

There are often complaints about films from our neck of the woods being stuffed with songs. While Project Ghazi does not have one, the film would leave you craving for a repeat of the worst song you might have heard in the ongoing decade. Some might even put their earphones on during the screening just to get something else in their ears.

School projects for seventh graders can produce a more watchable 100 minutes than Project Ghazi. It is just the latest – one of the worst – manifestation of the jump in the “revival” pool, eying all the leeway associated with it and none of the effort.

Humayun Saeed, one of the stars of the film had left the screening 20 minutes into the movie back in July 2017, which is all you needed to know about the initial release. Saeed told media that he did not want viewers to watch the movie in its then existing form, because it was “hard to listen to the dialogues.”

The producers decided rework the 2017 film and felt that all that needed fixing was done as it hit the theatres once again this year.

If one were forced to pick the worst thing about Project Ghazi it would perhaps be the editing and the action – both are performed with the technological finesse of a roadside butcher

In 20 months a new film can easily be made – an elaborately-thought-out one at that – which is perhaps what the filmmakers should have gone for, instead of just fixing sound issues, which ostensibly took almost two years.

Given the final product, perhaps the fact that people had a problem hearing what was being said on the screen might not have been that bad a thing for anyone associated with the film – especially their reputations as professionals. In fact, the filmmakers should have perhaps created a few visual problems as well, which would have forced us all to be kind to the film’s “attempt” having not known what exactly to criticize, so as to safeguard the “revival of Pakistani cinema”.

Another, more immediate, benefit of tampering with the film’s visuals would have meant that no one would have had any idea what was going on – which is precisely what one experiences with the visuals, but would then have been spared the optical torture.

The only science in the film is surrounding the fact that the movie has actually consumed money and human resources in order to come into being. And the real fiction lies in Project Ghazi self-identifying as a “film” that is made by those who do this for a living.

What is even more remarkable is that the film does so with a decent enough cast that features Humayun Saeed, Syra Shehroze, Shehryar Munawar and the veteran Talat Hussain.

The story revolves around a group of scientists headed by Dr Zaid (Talat Hussain) who tried to develop a new breed of advanced soldiers for Pakistan many years ago. The project was hijacked by some masked man, for reasons perhaps not even known to them. Salaar (Humayun Saeed), Zain (Shehryar Munawar) and Zara (Syra Shehroze) – who are all part of the line of defence without the viewer actually knowing which one does what – try to stop the evil forces, spearheaded by Qatan (Adnan Jaffar).

Acting is a part of the unmitigated shambles that Project Ghazi is, and individually critiquing each case would be as much a waste of our time – just as being a part of the film was a waste of theirs.

If one were forced to pick the worst thing about Project Ghazi it would perhaps be the editing and the action – both are performed with the technological finesse of a roadside butcher.

That someone chose to write the film is something that might need convincing as well. For while the butchery that the editing was results in a haphazard spectacle for the viewer – who can be surprised, shocked and bewildered, depending on how much the ticket cost as a percentage of their monthly income – there clearly is no defined script.

There are often complaints about films from our neck of the woods being stuffed with songs. While Project Ghazi does not have one, the film would leave you craving for a repeat of the worst song you might have heard in the ongoing decade. Some might even put their earphones on during the screening just to get something else in their ears.

School projects for seventh graders can produce a more watchable 100 minutes than Project Ghazi. It is just the latest – one of the worst – manifestation of the jump in the “revival” pool, eying all the leeway associated with it and none of the effort.