“Today, on 10th of April, 2022, welcome back to Purana Pakistan,” said Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, Chairperson Pakistan People’s Party, on the floor of the National Assembly. This was after Imran Khan was removed from the prime minister’s office through a vote of no-confidence. It was indeed a moment of relief, after weeks-long constitutional crisis that deepen day by day.

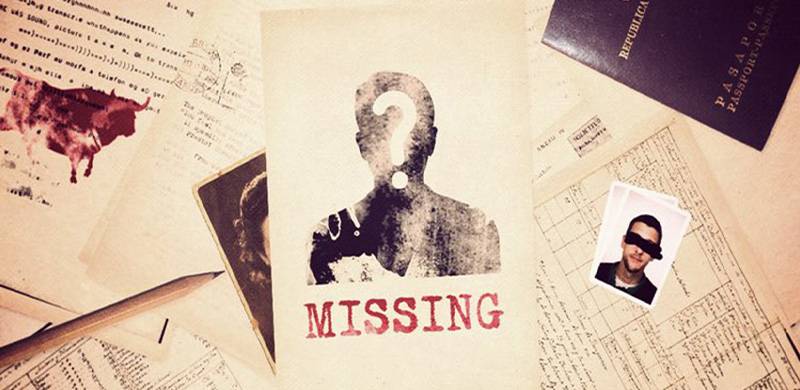

But, truth be told, the old Pakistan was no better than the new Pakistan. Take the case of missing persons. Baloch missing persons families have been relentlessly protesting on the streets for years. They have approached every possible forum for help, filed petitions in the courts, held a long march, ran online campaigns -- yet nothing has changed for them.

Pakistan, a democratic parliamentary republic, promises inalienable fundamental rights to its citizens through the 1973 constitution. It states that everyone shall enjoy the protection of law. It ensures civil liberties, Article 9, Article 10, 10-A, Article 14 and more. Further, under Article 7(i) of the Rome Statue, enforced disappearances constitute crimes against humanity -- meaning “acts when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack”.

Declaration for the Protection of All Persons Against Enforced Disappearances adopted by the UN General Assembly on 1992 states, ‘‘No circumstances whatsoever, whether a threat of war, a state of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked to justify enforced disappearances.”

Given the grave nature of the crime, it is tragic that the consecutive governments in Pakistan have failed to put an end to it. With no independent domestic legislation to criminalize enforced disappearances and torture, people detained outside the protection of law are without any safeguards as to their life and liberty. With no accountability mechanism employed to question and punish those who perpetuate this crime, the individuals involved easily evade responsibility.

However, the outgoing government did draft a bill to criminalize enforced disappearances, which was apparently passed by the relevant standing committee of the National Assembly, but was later reported to have gone “missing” after it was sent to the Senate, as was claimed by the then Human Rights Minister Dr Shireen Mazari. It is shameful that the chosen representatives of the people and the custodians of their rights seem completely helpless. Rather than taking staunch actions against state violence, they submit to the powers that be. They champion human rights as long as it is required to mobilize support, but once elected to their offices, they take no notice of human rights violations in the country. They become silent spectators when state apparatus is allegedly deployed to intimidate dissenting voices.

Therefore, it is important that a gentle reminder is given to the new government about the plight of the missing persons. Last October, Maryam Nawaz Sharif was seen standing in solidarity with the families of Baloch missing persons in Quetta. Addressing the jalsa, she not only acknowledged this serious problem facing Balochistan. She wondered how agonizing it must be for someone to not know whether their loved ones were dead or alive.

Now that her party is back in power, I am hopeful that the issue of enforced disappearances will top the PML-N agenda. The government must not only criminalize enforced disappearances and torture, but also put forth an effective mechanism to hold perpetrators accountable. The government must trace the whereabouts of missing persons, and ensure their immediate safe recovery.

It will be great to see if Maryam Nawaz continues to support voices of the missing individuals, and is able to ensure their issue is given space in the mainstream media.

Additionally, lawyers, journalists, academics, rights activists and civil society members must also raise their voice together in support of the rule of law. Otherwise, Naya or Purana Pakistan, all genuine efforts to make it a “better” country would symbolise nothing -- but an intra-class power struggle between the subculture elites.

But, truth be told, the old Pakistan was no better than the new Pakistan. Take the case of missing persons. Baloch missing persons families have been relentlessly protesting on the streets for years. They have approached every possible forum for help, filed petitions in the courts, held a long march, ran online campaigns -- yet nothing has changed for them.

Pakistan, a democratic parliamentary republic, promises inalienable fundamental rights to its citizens through the 1973 constitution. It states that everyone shall enjoy the protection of law. It ensures civil liberties, Article 9, Article 10, 10-A, Article 14 and more. Further, under Article 7(i) of the Rome Statue, enforced disappearances constitute crimes against humanity -- meaning “acts when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack”.

Declaration for the Protection of All Persons Against Enforced Disappearances adopted by the UN General Assembly on 1992 states, ‘‘No circumstances whatsoever, whether a threat of war, a state of war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked to justify enforced disappearances.”

Given the grave nature of the crime, it is tragic that the consecutive governments in Pakistan have failed to put an end to it. With no independent domestic legislation to criminalize enforced disappearances and torture, people detained outside the protection of law are without any safeguards as to their life and liberty. With no accountability mechanism employed to question and punish those who perpetuate this crime, the individuals involved easily evade responsibility.

With no accountability mechanism employed to question and punish those who perpetuate this crime, the individuals involved easily evade responsibility.

However, the outgoing government did draft a bill to criminalize enforced disappearances, which was apparently passed by the relevant standing committee of the National Assembly, but was later reported to have gone “missing” after it was sent to the Senate, as was claimed by the then Human Rights Minister Dr Shireen Mazari. It is shameful that the chosen representatives of the people and the custodians of their rights seem completely helpless. Rather than taking staunch actions against state violence, they submit to the powers that be. They champion human rights as long as it is required to mobilize support, but once elected to their offices, they take no notice of human rights violations in the country. They become silent spectators when state apparatus is allegedly deployed to intimidate dissenting voices.

Therefore, it is important that a gentle reminder is given to the new government about the plight of the missing persons. Last October, Maryam Nawaz Sharif was seen standing in solidarity with the families of Baloch missing persons in Quetta. Addressing the jalsa, she not only acknowledged this serious problem facing Balochistan. She wondered how agonizing it must be for someone to not know whether their loved ones were dead or alive.

Now that her party is back in power, I am hopeful that the issue of enforced disappearances will top the PML-N agenda. The government must not only criminalize enforced disappearances and torture, but also put forth an effective mechanism to hold perpetrators accountable. The government must trace the whereabouts of missing persons, and ensure their immediate safe recovery.

It will be great to see if Maryam Nawaz continues to support voices of the missing individuals, and is able to ensure their issue is given space in the mainstream media.

Additionally, lawyers, journalists, academics, rights activists and civil society members must also raise their voice together in support of the rule of law. Otherwise, Naya or Purana Pakistan, all genuine efforts to make it a “better” country would symbolise nothing -- but an intra-class power struggle between the subculture elites.