Are you a prose person or a poetry person? I would say there is no such thing as a prose person: prose is incidental to the genre in which it is employed. Indeed, much that is categorised or intended and conceived as poetry remains prosaic. So what makes us say ‘that’s poetry’? There is a quality of distillation: intensity of emotion; shorn of wordiness, self-indulgence and posturing; disciplined with felicity of language into aesthetic economy – not a word to be taken away, not a word to be inserted. The poetic statement denies question. And if this sounds excessive, just think of any line of poetry that you love – that stays with you – and then give thanks for genius that allows whole poems to form and become yours and where there is a literary tradition, part of the canon.

Poets are the glory of Urdu literature and even in the agonized, distorted propagandist construct that in Pakistan was made the matrix of cultural expression, the poetic tradition in Urdu thrives and delights. It speaks. It has not shown signs (fingers crossed) of succumbing to global pop. But there is that segment of our population that we once called ‘Anglicized’ and now yearningly term ‘English-medium’ sans rejectionist connotations of ‘maghrebzeda’: Are they destined to remain peripheral, weakly derivative? Yes – until a master or two gives voice. In doing just that, Adrian Husain’s collection of sonnets Italian Window demands an overture of welcome. And because literature can only be universal irrespective of the language, the collection will afford delight to any poetry lover as well as nurture thelocal tradition that has so far not sustained itself despite signs of promise.

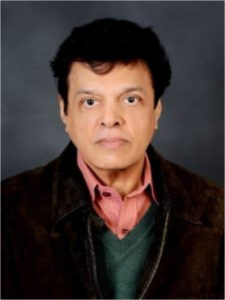

The poet Adrian Husain – Akkoo to friends here, Adrian to friends there, Dr Syed Akbar (or Adrian) Husain in his academic contexts – is, as the many cognomens would suggest, multi-faceted. In his earlier work he appears to wander despondently, seeking poetically to connect the parallel worlds he inhabits: which sometimes would keep him from connecting both within himself and locally with others. The poetic skill; the elegance, the nuances were characteristically ahead of direct apprehension by a poetry-loving audience that has not been ‘educated’ into ‘cultivated’ appreciation. Akkoo is himself far too intelligent to be an intellectual snob, but Adrian Husain’s appeal was for those who shared his sophisticated cultural context and struggling aspirants thereto who dared not frown or blink. Locally, his versification would, more often than not, leave the untutored untouched as well as unmoved – cognoscenti only.

Italian Window breaks that barrier.

Akkoo himself felt it was time to move beyond occasional poems towards a more complete ‘cohesive’ poetic statement. It emerged as a collection of sonnets: “I love the form. Its discipline structures what could otherwise be just a verbal explosion – implosion – ”he smiles and shrugs “the sonnets poured forth in a way that almost frightened me. I was doing one every day – sometimes two. The speed of it exhausted me but I couldn’t stop.” His personal catharsis materialises as poetry that any poetry lover can realise mysteriously, wanting to grasp a tantalising range of allusion rather than wish it away. In the Preface, Adrian declares his sonnets are autobiographical with ‘a vague confessional tone’. That could be why they reach the hidden self in all of us.

Both separately and in a unity of recollection, he recalls and re-experiences a child’s imprinted images and feelings with the adult’s subsequent reinterpretation of the initiation into the stuff of life: Love – sought, unfound – betrayed or unperceived – carnal, illusory. He views it all through his Italian Window in the country where much of it was experienced and his persona culturally engendered. From that deliberately taken perspective Adrian articulates a poignant alone-ness that journeys from abandon and accusation to detached understanding and the serenity of acceptance.

rompe-l’oeil, the sonnet that follows Prologue, ‘explains’ this:

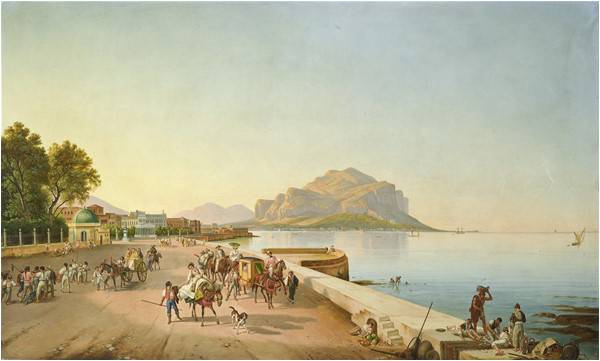

‘Mediterranean,’ he said, ‘heart of the world’

and there it was, suddenly, before me

the Italian coastline, sheer against the sky,

slope and sea unfurled

not by memory but the trick of a child

driven wonderstruck,

That child’s still there in a time inimical

reliving the past

How that word ‘inimical’ resonates! It relates equally to the nature of that time and the way ‘proving it home’ makes the present inimical. Adrian’s gift with words has concepts and images reinforce each other, making a richness of connections and recurring motifs within the sonnets. You see this faculty at work while the landscape unfurls along with his father’s ambassadorial flag fluttering memory,

playing a game

of mirrors, of signals flashed across time,

of blind sight . . . .

Happily for the vitality of the sonnets, Adrian’s use of classical reference effortlessly gives what could be the unfamiliar, substance in an emotional landscape. Though I must admit that Marcus Aurelius and good emperors in reverse in Absolution sends me looking for someone to please explain! Should I google or goggle? Adrian was lazy about not providing us with the convenience of an appendix.

Both separately and in a unity of recollection, he recalls and re-experiences a child's imprinted images and feelings with the adult's subsequent reinterpretation

The family tensions that grip the poet have a classic quality. Juggler encapsulates the poet’s image of his father. It is fair to say Adrian’s sonnets have their locus in the impact of his father’s personality and behaviour on the family

Austere

but sensuous, you stand six feet tall not far

from your diminutive wife with bleak stars

in her eyes . . .

(Shades)

although his mother is where he finds his Muse. The gentle wronged figure, devoid of anger, permeates the work:

like you Mother, outsmarted though never at a loss

losing all, though without counting the cost.

(Swimming-pool)

There is anger at the hurt inflicted on the young expectant woman; unvalued and cheated of love. But the infirmity of old age he witnesses in the mother he cherishes is chronicled with tenderness and empathy. Ultima Ora articulates a singularly contemporary experience of dying

She had become

mere machine, tied to her suffering, the sum

of no store of memories but a death-

less now.

The deliberate breaking of ‘deathless’ is another example of Adrian’s control and mastery of his craft: the punctuation becomes poetry.

Thematically the collection explores the non-dimensionality of time as well as a varying individual perception of it, within the chronological narrative that binds the sonnets. The poet says he would prefer them read sequentially. This critic finds no reason to do so or not do so. Let fancy rule and its fiats waver:

The moment lives in the mind, as does the toy

cart I never got in Palermo where the bay

was just an inlet for the sea

(Intermezzo)

In Capri:

It was a time that called back another

It was a crossing to hell

I can still see the drop/below.

The pain of a child, the groans/

within live – are ash-black roses – are thorns.

In Tabula Rasa:

So birdlike, memory lifts and ventures/across untried terrain – sea, swamp and snowdrift — /in search of food . . . .winning back the joyless faces and the mocking/ grin – redeemed, erased, by memory,/ a writing unwritten, a setting free.

The connotative content of ‘redeemed, erased’ and the dexterous ambiguity of ‘writing unwritten,’ keep coming back to tease and delight and set one a-thinking!

In Verso he tells us:

In the end, it is time reveals

theme and sense.

Unsure the auspices,

infirm all knowing – except backwards, like this.

In Bound:

I imagine a time neither present nor past

Words unsaid

are mulled over, not abandoned. Memory clings

like a shroud. We are made to belong.

(The startling ambivalence in the use of ‘made’ had me immediately reread the sonnet with an expanded meaning.)

Photographs have a special relevance capturing and mirroring moments, anachronistically significant: Reverie; Ephemera; gain in contrast as well as apposition to Sire – ‘father’s head in bronze’. Interiors and artefacts in the sonnets do not all pertain to Rome. In the sonnets relating to his mother, Portrait of a Lady, a few saris, old handbags and shoes remain. But a sense of the person lingers: known by her colours, pastels turning like rain.

Adrian declares his sonnets are autobiographical with 'a vague confessional tone'

The context and ambience are familiar almost homely. This is as appropriate and spontaneous in the context of these particular sonnets as the Renaissance prism is to others in the collection; and movement from one to the other is impelled quite naturally by the content of the poetic statement.

The last three lines of Verso crystallise Adrian’s apprehension of time. But if I were to choose one sonnet that embodies the mood and diction of the collection – its ‘poetic value’ – I would fix (right now, tomorrow I could choose another frame) on Ash Plume. It would be an injustice to the sonnet to sift phrases from the whole. Suffice it to say that the symbolism of the plume rising from Etna Pliny likened to an umbrella pine fuses into a poetic gem with the symbol of ‘you’ as – ‘your heart still beating – you turned to ash.’

In Italian Window Adrian Husain’s poetry turns to kundan.