Spending is the fun part of being in government. The real challenge—the part that separates the leaders from the lightweights—is making the people pay for what one is buying them. In other words, making them pay tax. Part of the trouble is that the bold, tax-collecting leader, can hardly boast about it. Voters do not usually like hearing that the government was very successful in squeezing more taxes out of them.

But with elections imminent, the concerned, enlightened citizen should worry about such things as the sustainability of government spending, and must answer the question: which party is best at collecting taxes? Or better yet, which party is the worst?

Luckily, with provincial taxes growing in importance, we have a track record to examine for all three major contenders. The answer to which party has done worst on the tax collection front will disappoint Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf diehards. Strangely for a government based on a movement that prioritizes tax reform, and idealizes Scandinavian social welfare states, the PTI-led Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government has been largely indifferent towards expanding its tax base and collecting more revenue.

To illustrate this shortcoming, compare its performance with that of the federation and its other provinces. And, finally, to understand what is causing it, we must begin with a bit of background.

In 2010, the 18th Constitutional amendment dramatically changed the relationship between the central and provincial governments. Key responsibilities such as education and health spending, were completely handed over to provincial capitals. To pay for these responsibilities, the provinces were given a larger share of the taxes collected by Islamabad (like federal income tax and customs duties), and were also given the ability to impose and collect new taxes.

Since the amendment was passed, the provinces have been exclusively responsible for, among other areas, agricultural income tax, sales tax on services, and property taxes. These new rights opened the door for more ambitious development plans than federal resources alone could pay for.

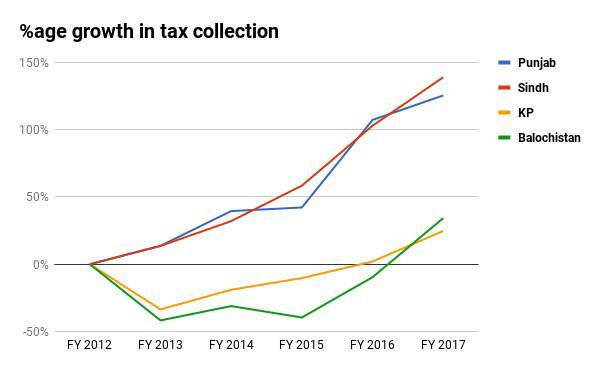

Consequently, after devolution, in most of the country (i.e. outside KP), provincial tax collection soared. Between fiscal year 2012 (the first full year of devolution), and fiscal year 2017, Punjab and Sindh’s revenue collection more than doubled, and Balochistan’s take grew 40%. Growing enforcement (increasingly, technologically assisted) of the provincial sales tax on services was the key driver of growth. Success in the provinces was accompanied by more effective enforcement of federal tax laws across the country as well—a bright spot for Mr Dar, amidst his otherwise mixed performance at the helm of financial affairs. Over the same five years, the PTI-led KP government’s provincial tax collection went up just 25% (in rupee terms which means it didn’t even keep pace with inflation).

So, Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad, and even Quetta have been tightening the screws. They have taken the share of taxation in our national income (tax as a percentage of GDP) from a pathetic 9% to a less pathetic 12.5% in the past five years. But during this time, Peshawar has been sitting on the sidelines. The PPP and PML-N, for all their faults, have demonstrably prioritized collecting tax in the areas under their charge, despite the political challenge of doing so.

It’s not as if there isn’t room for tax to grow in KP. A quick back-of-the-envelope calculation, overlaying estimates of provincial GDP shares with the latest GDP numbers, helps shed some light on this (provincial income shares are estimated by Dr Hafiz Pasha in a brilliant paper ‘Growth of the Provincial Economies – Institute for Policy Reforms’).

The share of provincial tax collection for KP, as a percent of total provincial income, works out to a little over half the percentage in Balochistan. Punjab’s is higher still, and Sindh’s tax-to-GDP ratio can be estimated at around four-fold that of KP. And none of the better-performing provinces have yet tapped into their full potential yet either. Agricultural income remains largely untouched, and property taxes are a shade of what they could be in a robust, well-documented system.

So why is KP’s performance so poor?

The State Bank, in its annual reports, without singling out KP (but while frequently noting progress and success in Sindh and Punjab), keeps lamenting the weakness of enforcement and collection institutions in the provincial governments as a key reason for low compliance with provincial tax rules. No rocket science here; the more serious a government is about enforcing its tax laws, the more likely it is to collect more tax. While the Punjab revenue authority is, by most accounts, breathing down businessmen’s necks, media reports and insider accounts describe the KP revenue authority as a skeletal organization, with practically non-existent enforcement capabilities and limited coordination with the more established excise and taxation department. To be fair to the PTI government, Sindh and Punjab did get a head-start on this front, setting up independent revenue authorities well before the last election. KP has also had a difficult law and order situation to deal with, though the same could be argued for Balochistan, which has still done better.

In any case, the relentless push towards meeting ambitious revenue targets that is seen in Sindh and Punjab, remains absent in KP. The PTI-led government in KP presents budgets that tend to announce lofty tax targets but are only followed by dramatic shortfalls.

The State Bank also repeatedly cites complacency as a factor for low provincial receipts. What this means is, with such a large percentage of provincial government expenditure being funded by distributions from the central government, there isn’t enough of an incentive for provinces to go about the difficult business of collecting tax. In the case of KP, which often struggles to spend its federal allocations in any case, there is an added source of complacency: hydel profits.

Hydel profits are royalties paid to provinces where dams are located, by electricity consumers across the country who pay this as part of their electricity bills. In KP’s case, these profits (which also include profits in arrears) have exceeded provincial tax collection in each year of the incumbent government. So, for now, perhaps there just hasn’t been enough pressure on the fiscal front for the KP government to get its act together.

As KP’s economy continues to grow though, hydel profits are unlikely to keep pace. If the PTI wins the province again, or if it wins the country, and is serious about its well-meaning health and education agenda, it will have to get serious about its taxation agenda as well. After all, Norway didn’t build a welfare state without taxing its citizens (38% tax-to-GDP ratio).

That’s all in the future now, whereas to answer the question with which we began—which party has been the worst at collecting tax—we must rely on past performance. The PTI-led KP government, campaigning on a tabdeeli slogan, had a unique chance to set an example of what a progressive, broad-based tax system might look like. So far, it appears to have been an opportunity wasted.

The writer is a Lahore-based columnist and consultant. He has previously served as a director in the global markets division of a major European investment bank. @AssadAhmad

But with elections imminent, the concerned, enlightened citizen should worry about such things as the sustainability of government spending, and must answer the question: which party is best at collecting taxes? Or better yet, which party is the worst?

Luckily, with provincial taxes growing in importance, we have a track record to examine for all three major contenders. The answer to which party has done worst on the tax collection front will disappoint Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf diehards. Strangely for a government based on a movement that prioritizes tax reform, and idealizes Scandinavian social welfare states, the PTI-led Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government has been largely indifferent towards expanding its tax base and collecting more revenue.

In KP's case, hydel profits have exceeded provincial tax collection each year of this government. So perhaps there just hasn't been enough pressure for the KP government to get its act together

To illustrate this shortcoming, compare its performance with that of the federation and its other provinces. And, finally, to understand what is causing it, we must begin with a bit of background.

In 2010, the 18th Constitutional amendment dramatically changed the relationship between the central and provincial governments. Key responsibilities such as education and health spending, were completely handed over to provincial capitals. To pay for these responsibilities, the provinces were given a larger share of the taxes collected by Islamabad (like federal income tax and customs duties), and were also given the ability to impose and collect new taxes.

Since the amendment was passed, the provinces have been exclusively responsible for, among other areas, agricultural income tax, sales tax on services, and property taxes. These new rights opened the door for more ambitious development plans than federal resources alone could pay for.

Consequently, after devolution, in most of the country (i.e. outside KP), provincial tax collection soared. Between fiscal year 2012 (the first full year of devolution), and fiscal year 2017, Punjab and Sindh’s revenue collection more than doubled, and Balochistan’s take grew 40%. Growing enforcement (increasingly, technologically assisted) of the provincial sales tax on services was the key driver of growth. Success in the provinces was accompanied by more effective enforcement of federal tax laws across the country as well—a bright spot for Mr Dar, amidst his otherwise mixed performance at the helm of financial affairs. Over the same five years, the PTI-led KP government’s provincial tax collection went up just 25% (in rupee terms which means it didn’t even keep pace with inflation).

So, Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad, and even Quetta have been tightening the screws. They have taken the share of taxation in our national income (tax as a percentage of GDP) from a pathetic 9% to a less pathetic 12.5% in the past five years. But during this time, Peshawar has been sitting on the sidelines. The PPP and PML-N, for all their faults, have demonstrably prioritized collecting tax in the areas under their charge, despite the political challenge of doing so.

It’s not as if there isn’t room for tax to grow in KP. A quick back-of-the-envelope calculation, overlaying estimates of provincial GDP shares with the latest GDP numbers, helps shed some light on this (provincial income shares are estimated by Dr Hafiz Pasha in a brilliant paper ‘Growth of the Provincial Economies – Institute for Policy Reforms’).

The share of provincial tax collection for KP, as a percent of total provincial income, works out to a little over half the percentage in Balochistan. Punjab’s is higher still, and Sindh’s tax-to-GDP ratio can be estimated at around four-fold that of KP. And none of the better-performing provinces have yet tapped into their full potential yet either. Agricultural income remains largely untouched, and property taxes are a shade of what they could be in a robust, well-documented system.

So why is KP’s performance so poor?

The State Bank, in its annual reports, without singling out KP (but while frequently noting progress and success in Sindh and Punjab), keeps lamenting the weakness of enforcement and collection institutions in the provincial governments as a key reason for low compliance with provincial tax rules. No rocket science here; the more serious a government is about enforcing its tax laws, the more likely it is to collect more tax. While the Punjab revenue authority is, by most accounts, breathing down businessmen’s necks, media reports and insider accounts describe the KP revenue authority as a skeletal organization, with practically non-existent enforcement capabilities and limited coordination with the more established excise and taxation department. To be fair to the PTI government, Sindh and Punjab did get a head-start on this front, setting up independent revenue authorities well before the last election. KP has also had a difficult law and order situation to deal with, though the same could be argued for Balochistan, which has still done better.

In any case, the relentless push towards meeting ambitious revenue targets that is seen in Sindh and Punjab, remains absent in KP. The PTI-led government in KP presents budgets that tend to announce lofty tax targets but are only followed by dramatic shortfalls.

The State Bank also repeatedly cites complacency as a factor for low provincial receipts. What this means is, with such a large percentage of provincial government expenditure being funded by distributions from the central government, there isn’t enough of an incentive for provinces to go about the difficult business of collecting tax. In the case of KP, which often struggles to spend its federal allocations in any case, there is an added source of complacency: hydel profits.

Hydel profits are royalties paid to provinces where dams are located, by electricity consumers across the country who pay this as part of their electricity bills. In KP’s case, these profits (which also include profits in arrears) have exceeded provincial tax collection in each year of the incumbent government. So, for now, perhaps there just hasn’t been enough pressure on the fiscal front for the KP government to get its act together.

As KP’s economy continues to grow though, hydel profits are unlikely to keep pace. If the PTI wins the province again, or if it wins the country, and is serious about its well-meaning health and education agenda, it will have to get serious about its taxation agenda as well. After all, Norway didn’t build a welfare state without taxing its citizens (38% tax-to-GDP ratio).

That’s all in the future now, whereas to answer the question with which we began—which party has been the worst at collecting tax—we must rely on past performance. The PTI-led KP government, campaigning on a tabdeeli slogan, had a unique chance to set an example of what a progressive, broad-based tax system might look like. So far, it appears to have been an opportunity wasted.

The writer is a Lahore-based columnist and consultant. He has previously served as a director in the global markets division of a major European investment bank. @AssadAhmad