The Perception

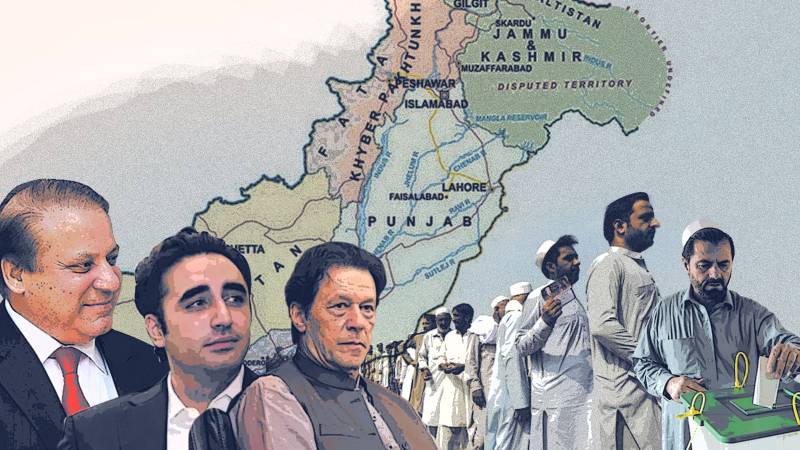

Perceptions and assumptions fill the void created by uncertainty. Thus far, in Pakistan, uncertainty is the name of the game regarding a general election that is to be held on February 8. This is not only, or really, about whether the election will be held or not, despite the fact that this question is often being asked by many.

There is enough evidence now to indicate that the elections will indeed take place unless a truly grave situation arises, such as a complete economic collapse or a spat of unprecedented terrorist attacks in major cities. The uncertainty which I am referring to has more to do with the question of whether Imran Khan's PTI will be able to conduct an effective election campaign with its core attraction, the former prime minister, in jail. He is facing the possibility of receiving long jail sentences.

The party's other prominent leaders, too, are behind bars or in hiding. PTI is now being run by competing groups of lawyers, most of whom have little or no experience in electoral politics. It can be safely assumed that due to the riotous actions of PTI supporters and party members on May 9 and 10 last year, and the apparently 'open and shut' nature of some of the cases Khan is being tried for, there is absolutely no likelihood of the party coming to power (through the coming elections).

However, a large number of PTI candidates have been 'allowed' to contest the polls. But one is not sure exactly how they will fare in a scenario in which the PML-N, after an arduous tussle with the previous military establishment (ME), now finds itself in the 'good books' of the current ME. On the other hand, the PPP is aggressively pushing to regain some of its lost electoral influence in Punjab.

Both parties were part of the coalition government that had replaced Khan's regime in April 2022 after it was ousted through a vote of no confidence in the parliament. The coalition regime was compelled to toe some harsh lines dictated by the IMF due to the dire economic circumstances left behind by Khan's government.

Till January 10 this year, there had not been any 'scientific' surveys conducted to test this perception. The only 'surveys' that did appear were in the shape of social media polls and 'walk arounds,' in which journalists go on a stroll in certain constituencies with a microphone and a video camera. These just can't be taken seriously

Consequently, the memory of the abject failures of Khan's regime began to be replaced by an equally abject reality in which the PML-N-led coalition government saw the imposition of one unpopular economic policy after another as it tried to stall the likelihood of Pakistan defaulting on its loans. This had become that government's narrative: 'Sacrificing its own popularity to save Pakistan.'

But it wasn't enough to appease middle and low-income groups impacted by unprecedented rates of inflation triggered by the 'sacrificial' policies. Nor could this narrative stop many people from forming a negative opinion about the coalition set-up, even though the unpopular policies largely mitigated the 'danger' of a possible default.

Did this regenerate Imran Khan's popularity that, by early 2022, had nosedived? This question transformed into a perception that began to gain traction among many journalists and analysts as well. 'PTI is very popular now' became the thing to say. But due to the aforementioned uncertainties, the media, really, has been all over the place, offering only superficial evidence of why it decided to adopt this perception.

PTI's astute social media teams succeeded in strengthening the said perception. Till January 10 this year, there had not been any 'scientific' surveys conducted to test this perception. The only 'surveys' that did appear were in the shape of social media polls and 'walk arounds,' in which journalists go on a stroll in certain constituencies with a microphone and a video camera. These just can't be taken seriously.

However, on January 11, a major survey finally appeared, conducted by Gallup Pakistan. The findings of this survey are rather interesting. It used a sample of around 5,000 voters in Punjab, Sindh, KP, and Balochistan. It was conducted between 'mid-December 2023 and January 5, 2024.' However, for some reason, the survey does not share any findings on Balochistan.

Punjab

Gallup's findings from Punjab challenge the mentioned perception. The survey suggests that PML-N's- approval ratings, which had drastically plunged when it was heading the coalition government, have witnessed a sharp increase. But PTI's ratings, which actually saw an increase during the coalition period, have steadily dropped. In March 2023, PML-N's approval rating in Punjab was just 25 percent. By December, however, it jumped to 32 percent. PTI's ratings in March 2023 had shot up to 45 percent, but dipped to 34 percent in December.

PML-N's ratings in Punjab are set to witness a further boost after the party kicks off its election campaign on January 15, led by its chief, Nawaz Sharif, now back from a self-imposed exile in England and cleared by the apex court to contest the election. Without Imran Khan in the field, PTI's ratings are likely to drop even further.

Many are expecting a 'different' or 'better' PML-N, which is now back under the leadership of Nawaz Sharif. The story of his return after being thrown out as PM by the previous ME in cahoots with a lopsided judiciary and a manic media, and in the process losing his wife due to illness, has found numerous sympathisers

The perception of PTI's resurgent popularity is likely to fail to convert itself into fact in Punjab. There are other variables in the province which too can work against PTI. For example, in 2018, the radical Barelvi Islamist party, the TLP, managed to usurp a chunk from PML-N and PPP vote banks. This had aided the PTI. This time, though, TLP is likely to eat into PTI's vote bank. This will certainly benefit PML-N. But it will also be interesting to see whether this, in any way, can aid the PPP in Punjab as well?

Apart from developing a dedicated vote bank of its own among sections of working-class and lower-middle-class Barelvi Punjabis (especially in central Punjab), TLP not only attracts the religious Punjabi Barelvi vote, but also voters who are angry or disappointed by the more mainstream parties.

Indeed, those angry with the economic policies of the PML-N-led coalition government may cast their votes for TLP, but many are expecting a 'different' or 'better' PML-N, which is now back under the leadership of Nawaz Sharif. The story of his return after being thrown out as PM by the previous ME in cahoots with a lopsided judiciary and a manic media, and in the process losing his wife due to illness, has found numerous sympathisers. On the other hand, the memory of the PTI government banning the TLP in 2021 is still fresh in the minds of core TLP supporters.

There is thus every likelihood that PML-N will emerge as the largest party in Punjab. Chances are that parties such as PPP, TLP, PML-Q and the newly formed IPP will all be gunning for second and third positions without seriously challenging a resurgent PML-N. Keeping in mind the Gallup survey, the perception of PTI increasing its electoral 'popularity' in Punjab is not compatible with the ground realities.

Sindh

In Sindh, the said perception is almost entirely negated in areas outside the province's capital city, Karachi. According to Gallup, the PPP enjoys 42 percent electoral support in Sindh, followed by PTI with 19 percent. The survey suggests that this percentage of PTI support in Sindh is almost exclusively rooted in Karachi.

The PPP has enjoyed a continuous streak of victories in Sindh since the 2008 elections. And there is nothing stopping the party from once again becoming the province's largest party in the coming elections. The economic and political interests of the Sindhi-speaking middle, working and peasant classes are tied to the PPP. The party works as a bridge between the Sindhis and the federation. This opens up wider economic and political opportunities for the Sindhis and aids their upward mobility. This is something that most Punjab and Islamabad-based analysts and media are only now realising. Yet, some still frame Sindh's politics in the most archaic and stereotypical manner.

PTI's electoral popularity peaked in Karachi during the 2018 election. PTI received a little over 17 percent of the total vote in Sindh in 2018, compared to PPP's 39 percent. According to Gallup, PPP's vote share is set to jump by up to 3 percent and PTI's by 2 percent. So what does this suggest?

The Mohajir vote stands scattered ever since the MQM broke into various competing factions in 2016. Electoral boycotts, in-fighting, and the removal of 'the father of Mohajir nationalism' Altaf Hussain as party head has turned MQM into a minor player in the city — despite the fact that many of the party's factions reunited recently

Whereas the PPP's vote percentage is likely to remain the same in Sindh (outside Karachi) as it was in 2018, it will possibly see an increase in Karachi. After the 2018 election, PTI's popularity in Karachi had quickly fallen by the wayside, creating a void which was further widened by MQM's continual splintering. With an aggressive campaign and support by its government in Sindh, the PPP succeeded in filling this void. This helped it win the 2023 mayoral elections in Karachi.

The 2 percent increase in PTI's popularity is certainly only rooted in Karachi. This may change, though. The JI was the other party that had benefitted in Karachi by MQM's sliding status and PTI's fading popularity. JI came second in the city's mayoral polls. It mostly received former PTI and former MQM votes in Mohajir-majority areas of the city, whereas the PPP not only regained the city's Sindhi and Baloch votes that it had lost to PTI in 2018, it also made electoral inroads in areas where the Pashtun are in majority. They had voted for PTI in 2018.

JI might struggle to sustain its resurgence in Karachi, though. It has no traction in the Sindhi and Baloch areas of Karachi which were won by the PPP during the mayoral elections. The Pashtun-majority areas may once again go for the PPP, or they might return to voting for PTI out of sympathy. But it is more likely that PTI's resurgence in the city will be shaped by Mohajir-majority areas that had voted for JI during the mayoral elections. These may return to vote for PTI. The fight in these areas of the city will largely be between PTI, JI, MQM and TLP.

The Mohajir vote stands scattered ever since the MQM broke into various competing factions in 2016. Electoral boycotts, in-fighting, and the removal of 'the father of Mohajir nationalism' Altaf Hussain as party head has turned MQM into a minor player in the city — despite the fact that many of the party's factions reunited recently. MQM will struggle to keep PTI, JI, PPP and TLP from further denting its once large vote bank. PTI and TLP had usurped the MQM vote in 2018. Now JI and PPP too would be looking to do the same. It is tough to predict which party will be able to win Karachi. The field in the city remains to be wide open.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

The perception of PTI's popularity is only substantiated by voter intention in KP where, according to the Gallup survey, PTI enjoys 45 percent of electoral support. The party had bagged 37 percent of the vote in KP in 2018. This means, PTI may see up to a 7 percent increase in its vote share here. However, the second major player in the province, the JUI-F, which bagged 11 percent of the vote in 2018, has seen a 3 percent increase in its popularity in KP.

The Pakhtun nationalist ANP, on the other hand, which had won the 2008 elections here, continues to lose ground to PTI and JUI-F. ANP won 10 percent of the vote in KP in 2018, but according to Gallup, its vote share may fall by another 3 percent in the coming elections.

Nevertheless, PTI had succeeded in creating a certain perception. But in most cases, 'popular' public sentiment is not always accurately or entirely reflected in the results of an election

Conclusion

There is still a whole month to go till the elections are held. Apart from the PPP, no other major party has really begun its election campaign. The campaigns are expected to start reaching a peak in the last few weeks leading up to the February polls. The country's political scenario has become extremely fluid. Making predictions is becoming tougher than ever. This fluidity began to set in after the fall of PTI's regime in April 2022. It became even more intense after the May 9 and 10 riots last year, which saw the ME begin to systematically dismantle the whole project that had first put PTI into power.

The Gallup survey suggests that even though PTI's wavering popularity witnessed a revival during the PML-N-led coalition government's struggle in repairing the country's vulnerable economics, the revival was more pronounced at least seven months ago when the perception of PTI's 'increasing popularity' wasn't even fully shaped by the party.

It was only during ME's crackdown against the PTI leadership (after the May 9 and 10 riots) that the party's social media wings began to earnestly shape the mentioned perception. It was also during this period that the larger media, too, began to adopt this perception. But the Gallup survey challenges various vital components of this perception. There were a handful of political commentators, though, who were questioning this perception, reminding that there were numerous variables which stops voter perception in becoming actual voter intention.

But surveys too can go horribly wrong. No matter how 'scientific', they too can produce findings based more on voter perceptions than on actual voter intentions. Here are a few examples: Just before the 1945 elections in Britain, the incumbent prime minister Winston Churchill's popularity ratings were at an all-time high. But his Conservative Party badly lost the election to the Labour Party. During the 1948 US presidential election, almost every major survey predicted that the Democratic Party candidate Harry Truman would lose to Republican Party's Thomas Dewey by a landslide. This indeed was the perception. But the opposite happened.

In 1970, surveys published by some leading newspapers in Pakistan predicted that that year's elections would produce a hung parliament. Instead, the Bengali nationalist party the Awami League (AL) swept the polls in East Pakistan, and the PPP swept West Pakistan's two largest provinces. A reporter from a major Urdu daily was quoted as saying that, after speaking to over four hundred voters during the week before the elections, he could've sworn that JI would sweep West Pakistan and also bag at least 40 percent of the seats in East Pakistan.

In 2004, all major surveys in India were predicting an easy win for the incumbent BJP. But it lost to the Congress Party. The Congress Party challenge just didn't figure in the perceptions doing the rounds before the polls. In 2016, only a handful of surveys were pointing towards Donald Trump's possible victory, yet he pulled off a major upset.

In a 2017 study by statisticians RS Kenett, D Pfeffermann,and DM. Steinberg, 'voter intent' may be influenced by perceptions created by a survey. There is evidence of a 'bandwagon effect,' in which voters shifted support to the candidate who was ahead in the survey polls.

Nevertheless, PTI had succeeded in creating a certain perception. But in most cases, 'popular' public sentiment is not always accurately or entirely reflected in the results of an election. Nor is public sentiment necessarily compatible with actual voter intent.

The 2024 elections will likely see PMLN regaining Punjab, and PPP retaining Sindh. PTI may once again win KP, but JUIF will win enough seats to form a coalition government there with the help of other parties and dent PTI's attempt to once again form a government in KP. Secondly, even if PTI wins KP, the party is likely to disintegrate with Khan in jail.