With deep sorrow, we announce the passing of Munir Attaullah, a remarkable intellectual, writer, journalist, athlete and beloved figure in Pakistan’s social and cultural landscape. With achievements across diverse fields and an inimitable ‘malang’ style, he lives on in the hearts of family, friends, and ‘fritterers’ across the globe.

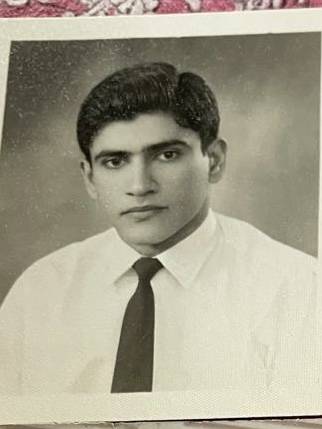

Munir showed exceptional intelligence from an early age. The family folklore has the six-year-old helping his older brother read the Holy Quran—sitting across from him and reading the Arabic script upside down. In class five, his Jesuit teacher at St Mary’s, Rawalpindi, called his parents to school and suggested advanced Math and Latin or the boy might become ‘lazy.’

In his early teens, he argued with his devout and practicing parents that he didn’t believe in God’s existence. Many adults in Pakistan’s deeply conservative society have taken such heresies to their graves out of love or fear of their parents. But Munir spoke his mind to authority at a young age.

Decades later, Munir explained how he formed this controversial opinion and the requisite courage by simply saying, “I went to the library, read up on the topic, and made up my mind by thinking about it logically.” He remained a lifelong rationalist who never bought into society’s myths and conventions, especially the much-vaunted value of hard work and conformity in general. He blossomed into something unique with his own take on life.

He articulated his philosophy decades later in the self-deprecating and humorous 500-word manifesto for his book “The Honourable Society of Fritterers.” He declared himself “the chairman for life–and after death–of the society” and explained that members were distinguished by the “belief that ‘striving’ and ‘competitiveness’ is, for the most part, an unnecessary waste of energy.” But this did not mean “low standards.” Fritterers aimed for “effortless superiority.” If this effortless effort required real effort–as it sometimes did, he acknowledged–then the work needed to be “cloaked in surreptitiousness.” The Chairman’s entire message and a copy of his book are available for free at Munir’s website: www.munirattaullah.com.

How much of Munir’s success was cloaked in surreptitiousness? By most accounts, at least his early academic success appeared genuinely effortless. In December 1955, at sixteen, he appeared for his Senior Cambridge exam and secured five distinctions, the highest score in South Asia. At Government College (GC) Lahore in 1956, he passed his FSc and stood 2nd in the Punjab. Continuing his education at GC, he studied Physics with Mathematics, two subjects he enjoyed throughout his life; one would always see a stack of books by his bedside with Quantum Physics featuring heavily (along with Evolutionary Biology, history, philosophy, and other subjects). Likely, his love for both subjects allowed him to excel during his undergraduate without sweating it. The fritterer stood second in Physics at the Punjab University and topped the University in Mathematics, despite arriving an hour late for his three-hour-long final!

Munir excelled in the hard sciences. He, however, was not your stereotypical reclusive, bespectacled nerd. Munir was the opposite. He loved socialising and sports. He was elected Secretary of the Students Union and Swim Team at GC. He was awarded the Punjab provincial colours for swimming and GC’s Sportsman-Scholar honour roll. During this time, the brashly charming teenager liberally indulged in ‘extracurriculars’ and ‘shenanigans’ to be expected of a star student-athlete in Lahore in the late 1950s.

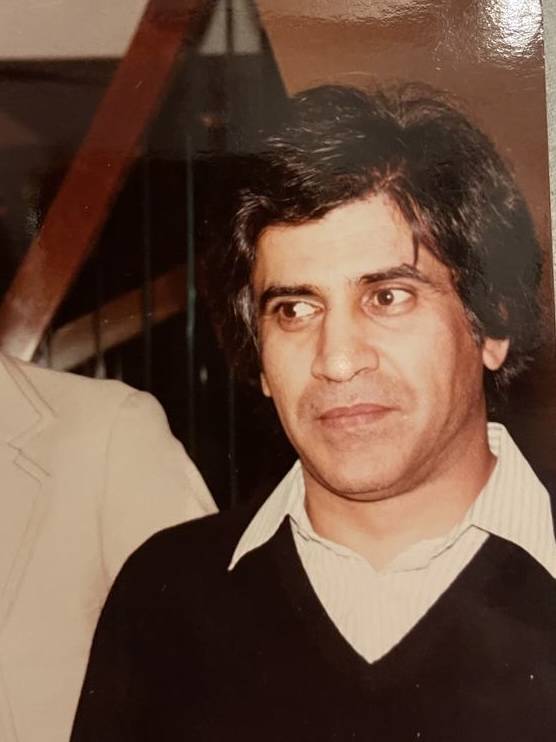

But what was he going to do professionally once he graduated? The dreaded grind--real life—lay waiting. Munir chose Law. He joined the prestigious Law College and stood second despite missing one paper because he overslept! Subsequently, he was awarded the much coveted Rhodes Scholarship and read law at Balliol College, Oxford. He had delayed the grind for just a bit longer. But not long enough. He returned to Pakistan briefly to work as a lawyer. He gave all of that up within a few months and returned to London. It set the trajectory for an unusual career and life.

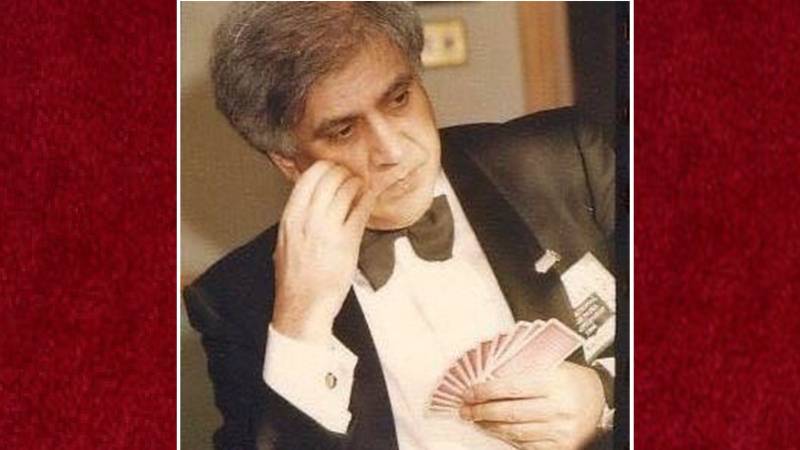

The ‘career’ barely lasted two years. IBM was the company to work for then, but the nine-to-five routine was unbearable. Working in sales, he achieved his allotted quota in “no time,” which allowed him to spend most of his time playing bridge, a new hobby. As he would do time and again, when Munir fell in love with a subject, skill, or sport, he quickly mastered it. Bridge was no different.

The Renaissance man wrote eloquently about politics, economics, science, philosophy, history, bridge, cricket, golf, poetry, arts and culture, and more. The columns were always easy reads, no matter the topic, but somehow still managed to pass on some wisdom that made one think or smile

He became a fixture in London’s glamorous 1960s bridge scene and started playing for stakes. The winnings from the bridge were sufficient to quit IBM. As he put it himself, by quitting, he had chosen to “more or less retire without a penny to his name.” Instead of choosing money, conformity, and the drudgery of doing what was expected of him, he chose to follow his passion. This passion for bridge led to an unorthodox lifestyle for a highly successful ‘fritterer.’

In time, he became a professional bridge player and represented Pakistan in international tournaments. In 1981, the Pakistan team surprised the world by reaching the final of the prestigious Bermuda Bowl. They came tantalisingly close to winning the tournament against the Americans thanks to a hand Munir played that was discussed in detail by the New York Times article the next day. Another Times article hailed him as the “Pakistani star who has been in two world championship finals. His name is Munir Ata-Ullah, but his friends call him Mooney.” His contributions to the game were honoured with a bridge convention named after him.

Making a living from bridge wasn’t easy. And the chairman of the fritterers must have had some ups and downs, financially and otherwise. But somehow, he, as he himself said, “successfully kept the wolf from the door in the relentless pursuit of having fun.”

While he continued to play bridge into his 60s, he found two new hobbies that morphed into professional successes in his 50s. Golf and journalism.

In the years he had his torrid ‘golf affair,’ he’d stand in the garden or in the courtyard at home, practicing his swing for hours, always smiling, never sweating. He was a regular at the Lahore Gymkhana Golf Club and went on to win the Lahore Seniors Golf Championship.

When an injury kept him from progressing in the sport, he decided to try his hand at journalism. In his manifesto as the chairman of the Society of Fritterers, he posed the question of what he would do next after golf as follows: “The next easiest option was to become a columnist and dispense superfluous and un-needed wisdom.”

He contributed a weekly column to the Daily Times–for over a decade. The Renaissance man wrote eloquently about politics, economics, science, philosophy, history, bridge, cricket, golf, poetry, arts and culture, and more. The columns were always easy reads, no matter the topic, but somehow still managed to pass on some wisdom that made one think or smile. He achieved this by mixing personal tales of travels and travails and encounters with people and places.

His brilliance shone through in pithy and concise declarations. For example, about human nature, he says, “The bitter pill of fact must dissolve in the sweet solvent of our beliefs if it is to be absorbed in our bloodstream of reality.” And his understanding of the world, “Democracy is a means, not an end; a mechanism, not a goal; and style, more than substance.” Above all was his sense of humour: “A stale columnist is no better than the romantic lead with halitosis.”

Accolades and prizes, including the 2nd prize in the Bastiat Prize for Journalism in 2004, rolled in. Some of his best articles were compiled into a book mentioned earlier (available for free on his website, munirattaullah.com).

Where others would have played it safe and stayed at IBM for financial security and social legitimacy, Munir chose to do his own thing. He had a surety about existence, its meaning or lack thereof, to lead a different kind of life. He loved the good life yet gave away money whenever he had lots, or even when he did not have much, to all and sundry. Mostly, he lived a simple life, a ‘malang’ who plunged to the depths of science and philosophy and all life had to offer. He took none of it too seriously. This was apparent as he moved–without fuss or tears–from bridge to golf to journalism. He didn’t cling to anything, including life, which eventually overtook him.

Life, like money, was just a means to an end: to enjoy friends and family, knowledge, hobbies, skills, all the gifts of nature. Instead of being a slave to another’s philosophy, guided on life’s journey by carrots and sticks, Munir relied on an inner compass that pointed to the north pole of his heart’s unique desires. Far from selfish, this made for a man who not only served up engaging ideas, fun conversation, and humour to all he met, he–without meaning to–served as an example of this other kind of life: about enjoyment, and more than that, about the pursuit of enjoyment. And doing that well.

He is survived by his wife, Farida, and son, Zulfi, and many friends, and admirers, who will remember his legacy as the Chairman for life–and after death–of the Society of Fritterers. May his life serve as an inspiration to all current and aspiring members.