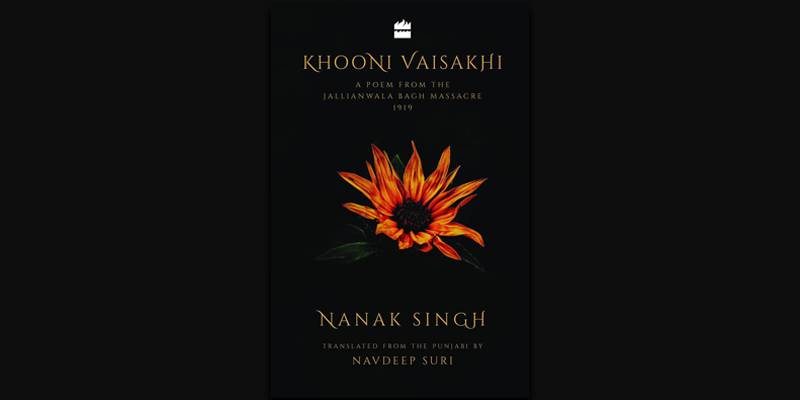

The bloody massacre at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar, a hundred years old this year, is both the end and beginning for Khooni Vaisakhi, Nanak Singh’s moving ode to the victims of that tragic episode, recently translated into English by Navdeep Suri, a career diplomat and Nanak Singh’s grandson. The backstory behind the poem should itself be the subject of another book, in how the poem was banned by the British upon its publication in 1920 just a year after the Amritsar tragedy; its existing copies burnt; and its rediscovery after sixty years before being rendered into English. That history alone makes this translation a literary event worth celebrating.

Nanak Singh passed away in December 1971, just a couple of weeks after the emergence of Bangladesh as an independent nation, having led an eventful life which was turned around by the Jallianwala Bagh tragedy in Amritsar; then as an ardent Sikh activist and freedom-fighter against British colonialism; and as a witness to the partition of India in 1947. Unfortunately, he is not very well-known in the land of his birth, a village near Pind Daadan Khan in Jhelum in modern-day Pakistan. I was acutely reminded of this injustice just recently when the installation of a statue of Punjab’s last indigenous ruler Maharaja Ranjit Singh at the Lahore Fort on the occasion of his 180th birthday attracted widespread attention, not least from fervent Punjabi nationalists. The reception given to a statue of the Maharaja was curious, even if deserved. For while his legacy is still a contested one, that of Nanak Singh is secure for posterity.

The doyenne of Punjabi fiction, Singh won the prestigious Sahitya Akademi and Punjab’s highest literary awards. I certainly hadn’t heard of him before this year, when I received a copy of Rakhshanda Jalil’s meticulously curated collection of literary writings on the Amritsar Massacre (to which I have myself contributed a humble translation of Krishan Chander) and which first exposed me to his work. My interest deepened after I read a story of his in translation and then actively sought out his evocative, largely autobiographical novel Adh Khidya Phul, translated as “A Life Incomplete”, also by his grandson Suri.

Singh wrote an astonishing 59 books, 38 novels and countless other plays, short-stories and even translations among them - concentrating on Punjabi. Importantly while in jail, he focused on the Hindi-Urdu novels of Munshi Premchand, as explained by the translator in his detailed essay on the poem. Suri’s translation of Khooni Vaisakhi is particularly pleasing. In his preface, he also explains his craft of translation, where “the translation must attempt to be faithful to the original – not just in terms of the content but also in its rhyme and cadence.” Following this admission, I became even more curious about the Punjabi original. Alas I cannot read the Gurmukhi Punjabi script.

While reading Khooni Vaisakhi, one feels that perhaps while the literature on the Jallianwala Bagh massacre is rich, it has not been adequately acknowledged as much on the Pakistani side of the border as on the Indian side. The Pakistanis are still heavily invested in, and saturated with, memories of the 1947Partition. The recent television treatments of Amrita Pritam’s partition novel Pinjar (as “Ghughi”) and Khadija Mastur’s novel Aangan on the same theme being cases in point. Partition also played a significant part in Singh’s own life, and he wrote novels like Agg di Khed, Khoon de Sohile and Manjdhaar on this theme (but those novels have yet to reach a wider audience outside Punjabi). The same can also be said about earlier and subsequent episodes of our collective historic memory – be it the War of Independence of 1857, the Salt March of 1930, the heroes of the Ghadar Movement including revolutionaries like Kartar Singh Sarabha and Bhagat Singh or the Royal Indian Naval Mutiny of 1946. There is a virtual silence over the events of 1971. Perhaps it is for us that Singh writes in the poem:

No plaque, no bust, no monument

To mark the place we died, O friends?

Khooni Vaisakhi begins with an invocation to Guru Gobind Singh and moves onto the 1919 Rowlatt Act Controversy, before describing in searing detail the main events leading up to that fateful evening of the 13th of April, 1919. For the high-school or even advanced graduate student in Pakistan, these verses might seem too detailed, even programmatic or propaganda, especially in a country where any part of history which had no direct connection with the formation of Pakistan is either omitted or reduced to a footnote. But one must imagine the context in which this poem was written: Nanak Singh as a shocked survivor of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, a mere 22-year old at the time, in a harshly repressive environment attempting to convey the anguish and accuracy of all that he had witnessed and survived with an economy of words, as swiftly as possible. For the uninitiated, however (and there will be many), the poem provides a welcome history lesson; and readers who would like more context and academic rigour are advised to read the accompanying essays by the translator on the link connecting the tragedy, the poem and the writer; as well as a moving personal recollection by Justin Rowlatt, a BBC correspondent and great-grandson of Justice Rowlatt, who authored the infamous Rowlatt Act which triggered the tragic series of events leading to the massacre in 1919; and the learned essay by Professor H.S. Bhatia putting Khooni Vaisakhi squarely within the protest poetry emanating from colonial Punjab in the 1920s.

What works for me is not only how faithfully Singh recounts the tragic and murderous events leading to the ill-advised measure by General Dyer, but also how the poem is an ode to the unity of Indians across caste, faith and nationality, especially in the section on “Ram Navami Celebrations Amid Hindu-Muslim Unity.”

Such harmony never seen before

Since God made this world, O my friends.

The seed of friendship between these faiths

Descended from heaven itself, my friends.

Discord and difference seemed to vanish

Each saw the other as brother, my friends.

In poetry, Singh reaches the same effect albeit more lyrically, which the celebrated writer Krishan Chander achieved in his singing prose in his short-story on the same incident titled “Amritsar, Azadi Se Pehle” in his 1948 collection Hum Vahshi Hen. Singh also lovingly invokes the spirits of the Sufi masters Mansur al-Hallaj and Shams-i-Tabrizi, likening their passion for martyrdom and truth to the martyrs of Jallianwala Bagh. Like Krishan Chander in the above-mentioned story, Singh does not forget the women who partook of their share in the tragedy, including sections on “Wives Mourn Their Husbands” and “The Lament of Sisters.”

It is clear after reading Khooni Vaisakhi as to why Singh has been described as the father of the Punjabi novel. The poem itself – like Krishan Chander’s aforementioned short story – is a popular and social history of Amritsar and the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, its immense value as a rare eyewitness account trumping any academic, more detached professional histories of the event.

The month of July played a crucial role in the lives of at least three central characters of the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre: Nanak Singh who was born on July 4, 1897, and survived the massacre to write Khooni Vaisakhi and countless other Punjabi classics; General Dyer, the Butcher of Amritsar, who died of arteriosclerosis, a lonely and secluded death on July 23, 1927; and Sardar Udham Singh, who assassinated Michael O’Dwyer, the Governor of Punjab at the time of the massacre. Udham Singh was hanged at Pentonville Prison in London on the 31st of July, 1940. He is said to have been a witness to the massacre in Amritsar like Nanak Singh. The two may or may not have met.

The pride of place in Khooni Vaisakhi, however, goes to Dyer, in the section titled “The Martyrs’ Certificate to Dyer”, which deserves to be quoted in full:

Shame on you, you merciless Dyer

What brought you to Punjab, O Dyer?

Not a sign of mercy unleashing such horror

How badly were you drunk, O Dyer?

You came here thirsting for our blood

Will a lake of it fill your greed, O Dyer?

So many innocents mowed down by you

The Almighty will demand answers, O Dyer.

You scoundrel! Who gave you the right

To make mincemeat of our patriots, O Dyer?

Wreaking terror upon us innocent folk

Did you fancy the taste of power, O Dyer?

Just as you riddled our bodies with bullets

You too will pay the price, O Dyer.

You’ll die and head straight to Hell!

Ah! Such torment awaits you there, O Dyer.

Coming face to face on that Judgement Day

What answers do you plan to give, O Dyer?

You Tyrant! Until the end of time you’ll be called

The Murderer that you are, O Dyer.

Our Lord will punish you for your crimes

Watch how you get destroyed, O Dyer.

Says Nanak Singh, Which holy book allows

For innocents to be butchered like this, O Dyer?

In his autobiography Meri Duniya, Singh wrote:

“My society and I – my humanity and my self – are so much in consonance that I can never ever think anything apart from them. If anything hurts my society or my humanity it hurts me.”

It is these values which illuminate his Khooni Vaisakhi and resonate with warning for the Dyers in our own time.

The writer is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and an award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore. He is the recipient of the prestigious 2013-2014 Charles Wallace Trust Fellowship in the UK for his translation and interpretive work on Saadat Hasan Manto’s essays. His most recent work is a contribution to the edited volume ‘Jallianwala Bagh: Literary Responses in Prose & Poetry’ (Niyogi Books, 2019). He is currently the President of the Progressive Writers Association in Lahore. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com

Nanak Singh passed away in December 1971, just a couple of weeks after the emergence of Bangladesh as an independent nation, having led an eventful life which was turned around by the Jallianwala Bagh tragedy in Amritsar; then as an ardent Sikh activist and freedom-fighter against British colonialism; and as a witness to the partition of India in 1947. Unfortunately, he is not very well-known in the land of his birth, a village near Pind Daadan Khan in Jhelum in modern-day Pakistan. I was acutely reminded of this injustice just recently when the installation of a statue of Punjab’s last indigenous ruler Maharaja Ranjit Singh at the Lahore Fort on the occasion of his 180th birthday attracted widespread attention, not least from fervent Punjabi nationalists. The reception given to a statue of the Maharaja was curious, even if deserved. For while his legacy is still a contested one, that of Nanak Singh is secure for posterity.

The doyenne of Punjabi fiction, Singh won the prestigious Sahitya Akademi and Punjab’s highest literary awards. I certainly hadn’t heard of him before this year, when I received a copy of Rakhshanda Jalil’s meticulously curated collection of literary writings on the Amritsar Massacre (to which I have myself contributed a humble translation of Krishan Chander) and which first exposed me to his work. My interest deepened after I read a story of his in translation and then actively sought out his evocative, largely autobiographical novel Adh Khidya Phul, translated as “A Life Incomplete”, also by his grandson Suri.

Singh wrote an astonishing 59 books, 38 novels and countless other plays, short-stories and even translations among them - concentrating on Punjabi. Importantly while in jail, he focused on the Hindi-Urdu novels of Munshi Premchand, as explained by the translator in his detailed essay on the poem. Suri’s translation of Khooni Vaisakhi is particularly pleasing. In his preface, he also explains his craft of translation, where “the translation must attempt to be faithful to the original – not just in terms of the content but also in its rhyme and cadence.” Following this admission, I became even more curious about the Punjabi original. Alas I cannot read the Gurmukhi Punjabi script.

While reading Khooni Vaisakhi, one feels that perhaps while the literature on the Jallianwala Bagh massacre is rich, it has not been adequately acknowledged as much on the Pakistani side of the border as on the Indian side. The Pakistanis are still heavily invested in, and saturated with, memories of the 1947Partition. The recent television treatments of Amrita Pritam’s partition novel Pinjar (as “Ghughi”) and Khadija Mastur’s novel Aangan on the same theme being cases in point. Partition also played a significant part in Singh’s own life, and he wrote novels like Agg di Khed, Khoon de Sohile and Manjdhaar on this theme (but those novels have yet to reach a wider audience outside Punjabi). The same can also be said about earlier and subsequent episodes of our collective historic memory – be it the War of Independence of 1857, the Salt March of 1930, the heroes of the Ghadar Movement including revolutionaries like Kartar Singh Sarabha and Bhagat Singh or the Royal Indian Naval Mutiny of 1946. There is a virtual silence over the events of 1971. Perhaps it is for us that Singh writes in the poem:

No plaque, no bust, no monument

To mark the place we died, O friends?

Khooni Vaisakhi begins with an invocation to Guru Gobind Singh and moves onto the 1919 Rowlatt Act Controversy, before describing in searing detail the main events leading up to that fateful evening of the 13th of April, 1919. For the high-school or even advanced graduate student in Pakistan, these verses might seem too detailed, even programmatic or propaganda, especially in a country where any part of history which had no direct connection with the formation of Pakistan is either omitted or reduced to a footnote. But one must imagine the context in which this poem was written: Nanak Singh as a shocked survivor of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, a mere 22-year old at the time, in a harshly repressive environment attempting to convey the anguish and accuracy of all that he had witnessed and survived with an economy of words, as swiftly as possible. For the uninitiated, however (and there will be many), the poem provides a welcome history lesson; and readers who would like more context and academic rigour are advised to read the accompanying essays by the translator on the link connecting the tragedy, the poem and the writer; as well as a moving personal recollection by Justin Rowlatt, a BBC correspondent and great-grandson of Justice Rowlatt, who authored the infamous Rowlatt Act which triggered the tragic series of events leading to the massacre in 1919; and the learned essay by Professor H.S. Bhatia putting Khooni Vaisakhi squarely within the protest poetry emanating from colonial Punjab in the 1920s.

What works for me is not only how faithfully Singh recounts the tragic and murderous events leading to the ill-advised measure by General Dyer, but also how the poem is an ode to the unity of Indians across caste, faith and nationality, especially in the section on “Ram Navami Celebrations Amid Hindu-Muslim Unity.”

Such harmony never seen before

Since God made this world, O my friends.

The seed of friendship between these faiths

Descended from heaven itself, my friends.

Discord and difference seemed to vanish

Each saw the other as brother, my friends.

In poetry, Singh reaches the same effect albeit more lyrically, which the celebrated writer Krishan Chander achieved in his singing prose in his short-story on the same incident titled “Amritsar, Azadi Se Pehle” in his 1948 collection Hum Vahshi Hen. Singh also lovingly invokes the spirits of the Sufi masters Mansur al-Hallaj and Shams-i-Tabrizi, likening their passion for martyrdom and truth to the martyrs of Jallianwala Bagh. Like Krishan Chander in the above-mentioned story, Singh does not forget the women who partook of their share in the tragedy, including sections on “Wives Mourn Their Husbands” and “The Lament of Sisters.”

It is clear after reading Khooni Vaisakhi as to why Singh has been described as the father of the Punjabi novel. The poem itself – like Krishan Chander’s aforementioned short story – is a popular and social history of Amritsar and the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, its immense value as a rare eyewitness account trumping any academic, more detached professional histories of the event.

The month of July played a crucial role in the lives of at least three central characters of the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre: Nanak Singh who was born on July 4, 1897, and survived the massacre to write Khooni Vaisakhi and countless other Punjabi classics; General Dyer, the Butcher of Amritsar, who died of arteriosclerosis, a lonely and secluded death on July 23, 1927; and Sardar Udham Singh, who assassinated Michael O’Dwyer, the Governor of Punjab at the time of the massacre. Udham Singh was hanged at Pentonville Prison in London on the 31st of July, 1940. He is said to have been a witness to the massacre in Amritsar like Nanak Singh. The two may or may not have met.

The pride of place in Khooni Vaisakhi, however, goes to Dyer, in the section titled “The Martyrs’ Certificate to Dyer”, which deserves to be quoted in full:

Shame on you, you merciless Dyer

What brought you to Punjab, O Dyer?

Not a sign of mercy unleashing such horror

How badly were you drunk, O Dyer?

You came here thirsting for our blood

Will a lake of it fill your greed, O Dyer?

So many innocents mowed down by you

The Almighty will demand answers, O Dyer.

You scoundrel! Who gave you the right

To make mincemeat of our patriots, O Dyer?

Wreaking terror upon us innocent folk

Did you fancy the taste of power, O Dyer?

Just as you riddled our bodies with bullets

You too will pay the price, O Dyer.

You’ll die and head straight to Hell!

Ah! Such torment awaits you there, O Dyer.

Coming face to face on that Judgement Day

What answers do you plan to give, O Dyer?

You Tyrant! Until the end of time you’ll be called

The Murderer that you are, O Dyer.

Our Lord will punish you for your crimes

Watch how you get destroyed, O Dyer.

Says Nanak Singh, Which holy book allows

For innocents to be butchered like this, O Dyer?

In his autobiography Meri Duniya, Singh wrote:

“My society and I – my humanity and my self – are so much in consonance that I can never ever think anything apart from them. If anything hurts my society or my humanity it hurts me.”

It is these values which illuminate his Khooni Vaisakhi and resonate with warning for the Dyers in our own time.

The writer is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and an award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore. He is the recipient of the prestigious 2013-2014 Charles Wallace Trust Fellowship in the UK for his translation and interpretive work on Saadat Hasan Manto’s essays. His most recent work is a contribution to the edited volume ‘Jallianwala Bagh: Literary Responses in Prose & Poetry’ (Niyogi Books, 2019). He is currently the President of the Progressive Writers Association in Lahore. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com