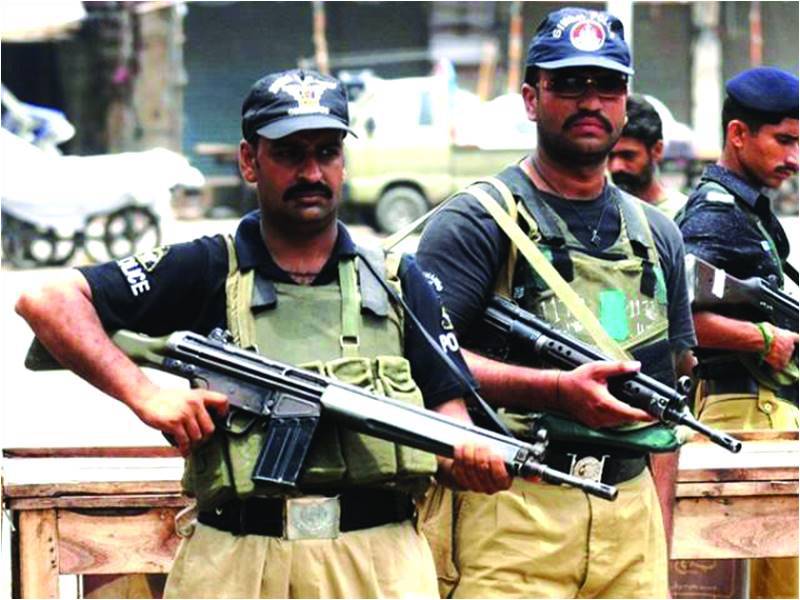

Extra-legal killings by police authorities have become a standard practice in Pakistan. The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan in its yearly flagship report published in 2020 has deplored the growing number of killings by police in alleged encounters. Such killings can be termed as cold-blooded murders, which are prohibited under both national and international law. The Constitution of Pakistan accords every person the right to life and the right to a fair trial under Article 9 and 10A respectively. Even persons accused of heinous offences like rape and murder have a constitutional guarantee to be proceeded against in accordance with law and cannot be arbitrarily deprived of their life by extrajudicial means.

The Supreme Court of Pakistan in the case of Benazir Bhutto vs. President of Pakistan PLD 1998, 388, termed extrajudicial killings as being invalid, illegal and improper as well as equated the prevalence of such killings with the law of jungle. Additionally, such killings violate provisions of key international human rights instruments, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, both of which are binding on Pakistan.

Despite the unlawfulness of such incidents of police excess, these killings are rampant in Pakistan, with hundreds of people being assassinated every year extra-legally by police authorities according to Human Rights Watch. The predominant factor contributing to this widespread illegal practice is the ostensible impunity enjoyed by police officials. Perpetrators are seldom prosecuted for their crimes and convictions are rare. A recent example in this context is the harrowing incident of Sahiwal police encounter, which shook the nation’s conscience. However, all personnel accused in this tormenting incident were acquitted by an anti-terrorism court in October last year due to lack of evidence and by extending them benefit of doubt. Another instance of such blatant impunity is the case of SSP Rao Anwar who is accused of killing at least 444 people in police encounters, including Naqeebullah Mehsud. The police official has until now managed to evade the grab of law despite the Supreme Court’s suo motu notice against him. Another cause of extrajudicial killings in Pakistan is the fact that these killings are at times part of official policy as a means of eliminating crime. Such killings are carried out with either express or implied approval of senior police officials. The justification for perpetuating such an inhumane policy is often premised on the inefficacy of the criminal justice system, which is marred by exceptional delays and a lengthy appeals process that makes it extremely difficult for police authorities to secure prompt convictions. Such killings are henceforth seen as a means of ensuring that habitual offenders do not go scot-free due to inadequacy of evidence and witnesses against them. The official policy garners further support from the societal response, which often ranges from tacit approval to outright praise for such police tactics seen as an efficient way of curtailing the high crime rate. These killings are, however, condemned by pro-right activists and civil society organizations due their inherent immoral and illegal nature.

While police authorities are at the forefront of this issue, the longstanding nuisance of extrajudicial killings can only be countered by adapting a multipronged strategy. The Police Order 2002 provides for the establishment of Public Safety Commissions at district and provincial level. These commissions will prove to be a viable step in disciplining police authorities by referring them complaints regarding extra-legal killings for independent enquiry and assessment. Furthermore, superior police officials should also be investigated and prosecuted for staged police encounters committed within their jurisdiction. According to section 155 and 156 of the Police Order 2002, police officers found guilty of misconduct including torture can face prison terms from three to five years. The implementation of existing legal safeguards and ensuring across the board accountability can deter police officials from taking law into their own hands.

Furthermore, the need for an external and independent agency, which is supported by the civil society and international community for the purpose of establishing an effective public oversight of police, was also highlighted by the report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions published in 2010. Such an agency is the need of the hour due to the inherent and inevitable bias found in police investigations probing internal departmental wrongdoings and misconduct. The government needs to promulgate legislation specifically defining and outlawing extrajudicial killings in line with the United Nations Principles on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extra-legal, Arbitrary and Summary Executions, 1989. These principles along with the Minnesota Protocol on the Investigation of Potentially Unlawful Death, 2016 provides an internationally accepted legal framework for preventing and investigating unlawful deaths. Proscribing extrajudicial killings will go a long way in removing the trust deficit between the police and the public and will reinforce the image of the police as a peoples’ friendly force.

The writer is a lawyer and can be reached on Twitter @usamamaalik1

The Supreme Court of Pakistan in the case of Benazir Bhutto vs. President of Pakistan PLD 1998, 388, termed extrajudicial killings as being invalid, illegal and improper as well as equated the prevalence of such killings with the law of jungle. Additionally, such killings violate provisions of key international human rights instruments, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, both of which are binding on Pakistan.

Despite the unlawfulness of such incidents of police excess, these killings are rampant in Pakistan, with hundreds of people being assassinated every year extra-legally by police authorities according to Human Rights Watch. The predominant factor contributing to this widespread illegal practice is the ostensible impunity enjoyed by police officials. Perpetrators are seldom prosecuted for their crimes and convictions are rare. A recent example in this context is the harrowing incident of Sahiwal police encounter, which shook the nation’s conscience. However, all personnel accused in this tormenting incident were acquitted by an anti-terrorism court in October last year due to lack of evidence and by extending them benefit of doubt. Another instance of such blatant impunity is the case of SSP Rao Anwar who is accused of killing at least 444 people in police encounters, including Naqeebullah Mehsud. The police official has until now managed to evade the grab of law despite the Supreme Court’s suo motu notice against him. Another cause of extrajudicial killings in Pakistan is the fact that these killings are at times part of official policy as a means of eliminating crime. Such killings are carried out with either express or implied approval of senior police officials. The justification for perpetuating such an inhumane policy is often premised on the inefficacy of the criminal justice system, which is marred by exceptional delays and a lengthy appeals process that makes it extremely difficult for police authorities to secure prompt convictions. Such killings are henceforth seen as a means of ensuring that habitual offenders do not go scot-free due to inadequacy of evidence and witnesses against them. The official policy garners further support from the societal response, which often ranges from tacit approval to outright praise for such police tactics seen as an efficient way of curtailing the high crime rate. These killings are, however, condemned by pro-right activists and civil society organizations due their inherent immoral and illegal nature.

Perpetrators are seldom prosecuted for their crimes and convictions are rare. A recent example in this context is the harrowing incident of Sahiwal police encounter

While police authorities are at the forefront of this issue, the longstanding nuisance of extrajudicial killings can only be countered by adapting a multipronged strategy. The Police Order 2002 provides for the establishment of Public Safety Commissions at district and provincial level. These commissions will prove to be a viable step in disciplining police authorities by referring them complaints regarding extra-legal killings for independent enquiry and assessment. Furthermore, superior police officials should also be investigated and prosecuted for staged police encounters committed within their jurisdiction. According to section 155 and 156 of the Police Order 2002, police officers found guilty of misconduct including torture can face prison terms from three to five years. The implementation of existing legal safeguards and ensuring across the board accountability can deter police officials from taking law into their own hands.

Furthermore, the need for an external and independent agency, which is supported by the civil society and international community for the purpose of establishing an effective public oversight of police, was also highlighted by the report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions published in 2010. Such an agency is the need of the hour due to the inherent and inevitable bias found in police investigations probing internal departmental wrongdoings and misconduct. The government needs to promulgate legislation specifically defining and outlawing extrajudicial killings in line with the United Nations Principles on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extra-legal, Arbitrary and Summary Executions, 1989. These principles along with the Minnesota Protocol on the Investigation of Potentially Unlawful Death, 2016 provides an internationally accepted legal framework for preventing and investigating unlawful deaths. Proscribing extrajudicial killings will go a long way in removing the trust deficit between the police and the public and will reinforce the image of the police as a peoples’ friendly force.

The writer is a lawyer and can be reached on Twitter @usamamaalik1