The Pakistani male is a paradox, an omnipotent and fragile creature, complex yet one-dimensional, a wise fool, rigidly geometrical but frequently impressionable, longingly liberal yet arrested by the throes of tradition, occasionally scintillating but often repetitive and unimaginative. This puzzling contradiction will at times have you deeply drawn and at others, equally extracted, driving you to place one foot on the accelerator and the other perpetually on the brakes. Eventually, you’ll pause and wonder: non-binaries are usually good, but what goes into the making of such incongruity?

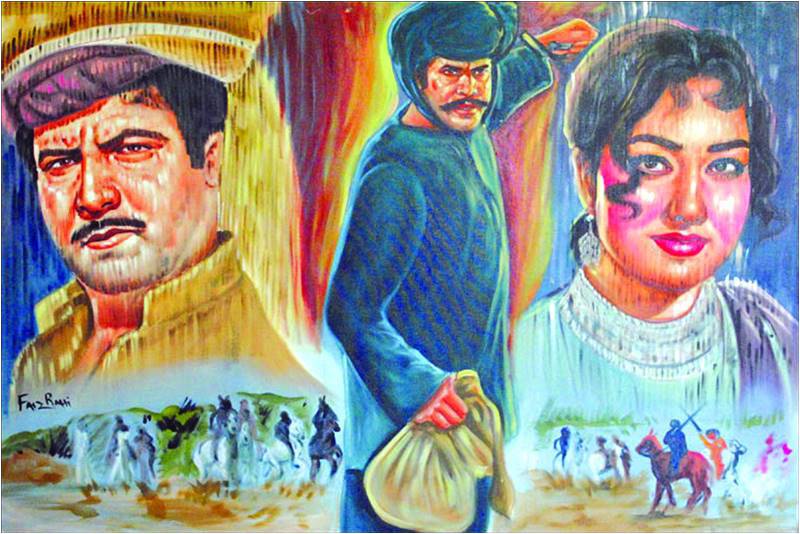

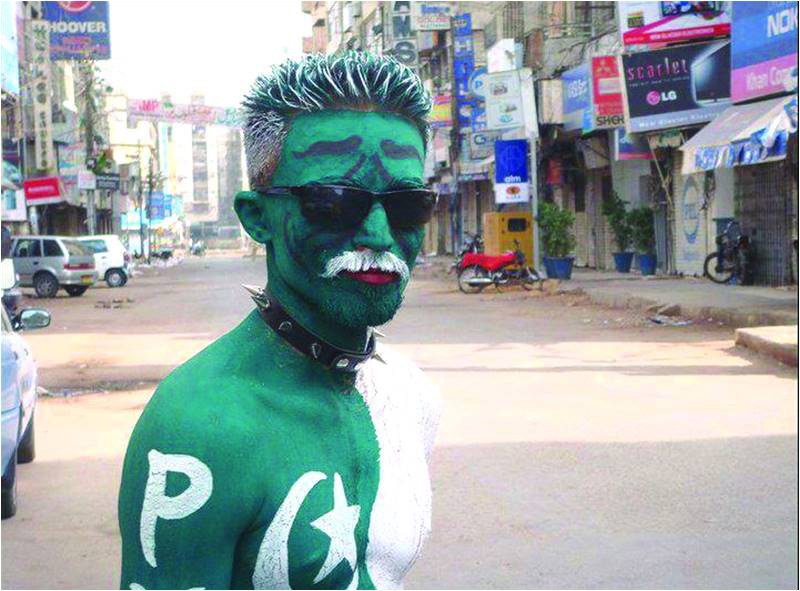

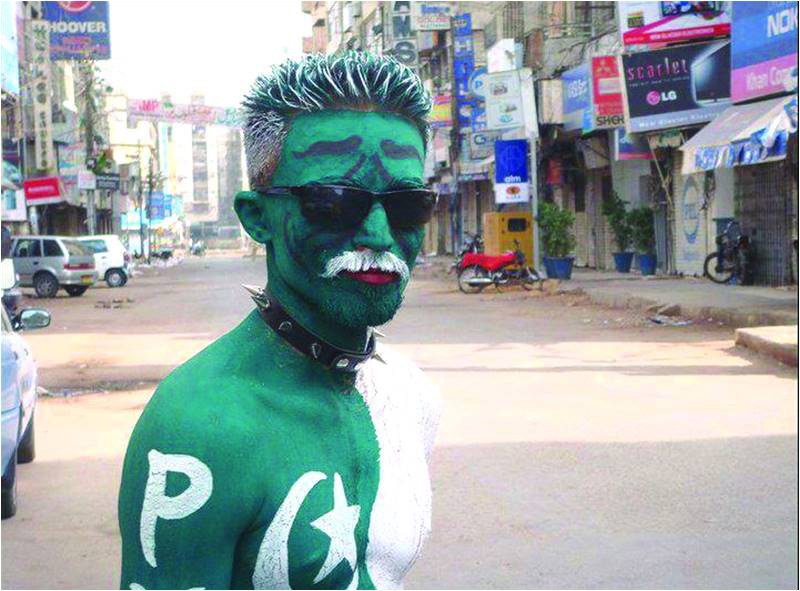

For a second, imagine hundreds of miniature cobwebs hanging from their rafters, sculptures of silky strands, encased in layers of dust, as the engineers of these masterpieces cling fiercely to the perimeters of their web. Pakistani men are vaguely resonant of these engineers, and their layered, entangled cobwebs represent a central tension in their lives: the relentless push and pull between demands of their traditional, patriarchal, impassive upbringing – which may or may not bear religious undertones – and the pressures and magnetic tug of modernity, a yearning to appear liberal and “cool”, of having kept up with the times. Amidst such a maze-like, ambiguous backdrop, an ensuing identity crisis is hardly startling.

Admittedly, the grouping is broad, rendering it unfair to paint every Pakistani man with the same wide-stroked brush. Variations, individual nuances, even outliers must be accounted for to depict a fair picture. However, there are enough commonalities threading through the classification of “elite” Pakistani men, which allow a predictable pattern to emerge and be woven.

Most will declare poker-faced, “I’m not a WhatsApp person”. Beyond the apparent insouciance of the proclamation, this beckons at a more profound hitch in male psyche and nurturing, signaling the twists and turns of how things have come to this. The Pakistani man is raised with an instrumental view to life, and his sense of self is intimately bound to functional titles, promotions and paychecks. This relationship for him is fundamental. Life is an adjunct to office meetings, conference calls, more recently Zoom sessions, and eventually Netflix to wind down the day. Being pulled in a million directions at work, occupational busy-ness is a badge of honor, amplifying his marketplace salability, and possibly making him even more of a “man” - which is the ultimate goal.

Now this isn’t always by choice, for there are obligations that must be met and bills that must be paid; nor is it all bad news, for being output driven and professionally committed suggests he will unlikely shirk responsibility and lapse into freeloader mode. In fact, the probability that he will come through at moments that matter is suspiciously high, for the Pakistani man knows when to pull out the benevolent, protective card. But the question becomes: as pivotal as it is to be there when a crisis erupts, should it be enough to get a clean chit for everything else that’s flouted?

Whatever of introspection, erecting companionship, bolstering friendships that don’t offer conventional returns on investment, but may be an end in themselves, without which most humans feel adrift?

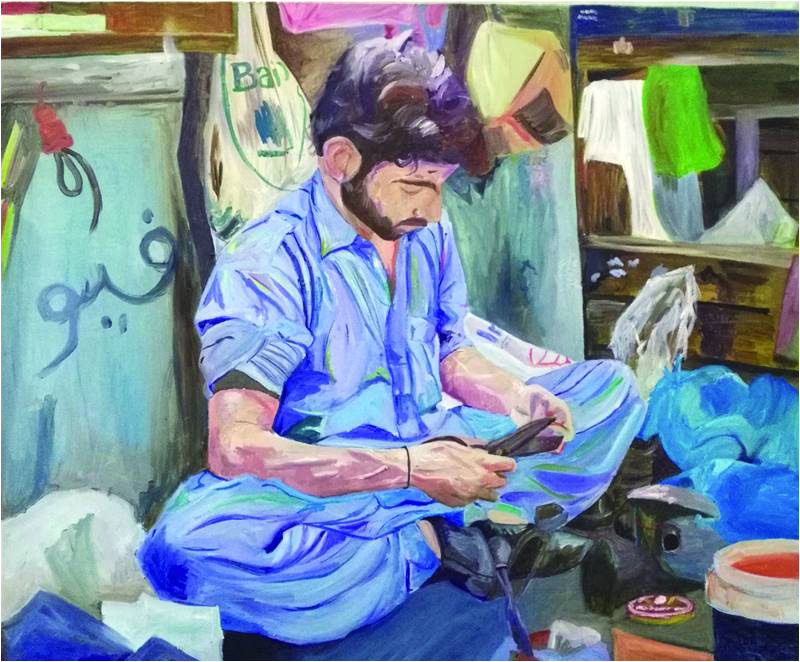

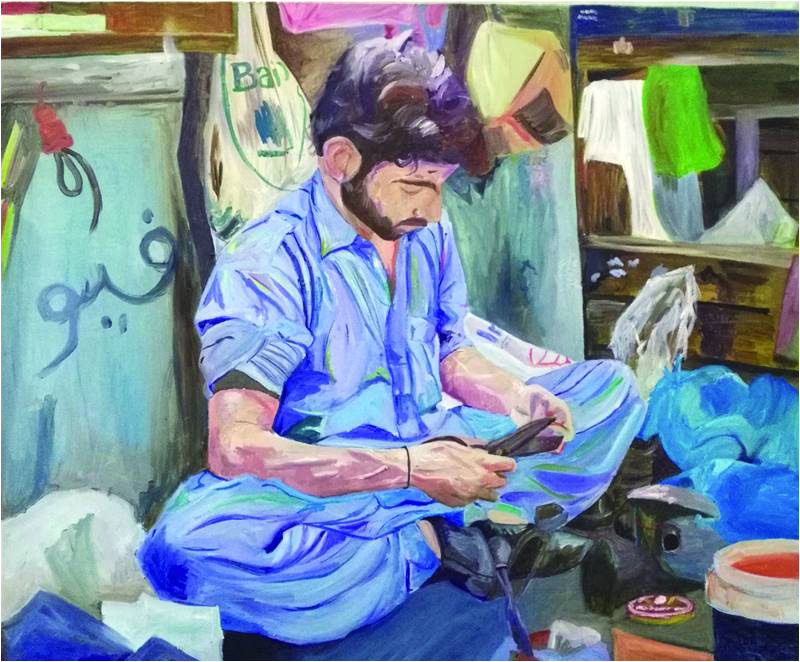

The Pakistani man is in fact unique: rarely raised to explore, question, reconnoiter, even challenge the notion of friendship – particularly with the opposite sex – as a pursuit of mere platonic happiness that won’t tick any material or strategic boxes, such as marriage. They are mostly absorbed in taking themselves too seriously, meticulously planning ahead, other times absorbed in a mindless passing of time, as long as it doesn’t demand reflective energy and thought, oblivious to the possibilities of drawing meaningful human connection.

Although social and political awareness for most Pakistani men is limited to news and social media, occasionally, you’ll stumble upon one who will surprise you with his creative fibre and rustic humour; initially, you’ll find it appealing. He’ll relish your access to the unguarded world, tap into your flaws and anxieties, examine books and ideas, culture and travelogues with you — even welcome your proclivity to speak your twisted mind, stir emotions and polemics – turning on its head the common myth that Pakistani men prefer girls who are seen and not heard; visually attractive but muted women. For a while you’ll believe he is willing to invest in the exchanges and connection, live life in all its dimensions, and go along.

Unfortunately, though, years of socialization and chains that he has forged around himself won’t let the magic hold, and disappointment will quickly set in. A manic daily routine, fragile egos, latent insecurities, even boredom may set in. The Pakistani man wants to witness tangible scores and outcomes to this giant friendship experiment he has hurled himself into. As a woman, therefore, you are constantly under fear of friendship attrition, strained by the pressures of inventing spanking new ways of keeping your Pakistani friend hooked and at the center. It can become grueling, mirroring some kind of work mandate with clearly stated benchmarks and targets that must be met to ward off the threat of lay-off. That was never the point, was it? Isn’t that what differentiated friendships from tactical transactions in the first place? Eventually, when it starts eroding, the loss to you will feel literal – a collapsing alliance that was carefully yet naturally curating – but also abstract: the loss of your belief in rapport, and solidarity, of a coalition that felt possible between good friends.

The few attachments that Pakistani men unconditionally forge and ungrudgingly perform are blood ties; parents, siblings, their own children, maybe even a partner (although that isn’t necessarily a blood relation). Holding on to your family’s apron strings, whilst occasionally frustrating, is honorable and something to preserve over generations. It produces a rich tapestry of culture and tradition, differentiating us from the West. But why the emotional quotient and desire to devote must saturate as soon as Pakistani men leave familial parameters appears less intuitive.

Of course, there is the back story of the obsession with masculinity, of having to appear in control at all times, with no room to express vulnerability or dependency, especially not neediness toward a female friend. There’s also a mindset spurred by hardheaded rationality, general reluctance to invest time, and an inability to appreciate the more elusive aspects of “what’s in it for them”; in other words, unless the benefits of a friendship are hitting hard in the face or brought as proof in a hand basket, it’ll be a tough sell to a Pakistani man.

This might be a good moment to clarify that I’m not a firebrand feminist whose mantra rests on male bashing. On the contrary, I depart from many assorted brands of women’s lib in Pakistan, masquerading as feminism, and find them thorny, cloned from western counterparts and unsatisfying. I’m also not a gender labeler, looking to caricature all Pakistani men as one indistinguishable lot. I don’t think I’m mad at men either, because anger, whilst potentially constructive, is rarely enough on its own. Perhaps I’m bewildered and somewhat disillusioned.

The majority of my handful of close friends and confidantes are Pakistani men and there is much to be celebrated about them. What’s more corrosive and frustrating, however, is the large brand of Pakistani men that purposefully reject the quest for self-discovery, to develop the capacity to understand first themselves and then another, spend energies constructing camaraderie, express spontaneously and sensitively, and realize that occasionally surrendering to vulnerability and free emotion doesn’t detract from manliness and appeal. To try and seek out those who believe that a life exists beyond corporate corridors and reaping professional rewards, one that is filled with expectation and wonder, and conversations which may not yield immediate gratification in the form of fiscal spur but may light up a dull, self-isolating evening, yielding deferred sentimental purchase. That to become a “WhatsApp person” to sustain such a friendship may be worthwhile after all.

I think these things often, hope for them to change, but cannot help asking whether, in a society where men are yet to be negatively sanctioned for side-stepping domestic duties and childcare, where the common male ego-led logic is never to lose an argument but instead, lose a friend, where days and nights are spent figuring out one’s mark-to-market worth, my expectation is premature and misplaced. That for now, perhaps, unearthing the topsoil and repurposing Pakistani men, their life and ambitions, towards discovering curiosity, companionship and consistency, sparking the realization that time doesn’t always have to mean money, must remain a dream deferred.

Saba Karim is an Instructor at New York University’s campus in Abu Dhabi and author of the forthcoming novel, Skyfall

For a second, imagine hundreds of miniature cobwebs hanging from their rafters, sculptures of silky strands, encased in layers of dust, as the engineers of these masterpieces cling fiercely to the perimeters of their web. Pakistani men are vaguely resonant of these engineers, and their layered, entangled cobwebs represent a central tension in their lives: the relentless push and pull between demands of their traditional, patriarchal, impassive upbringing – which may or may not bear religious undertones – and the pressures and magnetic tug of modernity, a yearning to appear liberal and “cool”, of having kept up with the times. Amidst such a maze-like, ambiguous backdrop, an ensuing identity crisis is hardly startling.

Admittedly, the grouping is broad, rendering it unfair to paint every Pakistani man with the same wide-stroked brush. Variations, individual nuances, even outliers must be accounted for to depict a fair picture. However, there are enough commonalities threading through the classification of “elite” Pakistani men, which allow a predictable pattern to emerge and be woven.

Most will declare poker-faced, “I’m not a WhatsApp person”. Beyond the apparent insouciance of the proclamation, this beckons at a more profound hitch in male psyche and nurturing, signaling the twists and turns of how things have come to this. The Pakistani man is raised with an instrumental view to life, and his sense of self is intimately bound to functional titles, promotions and paychecks. This relationship for him is fundamental. Life is an adjunct to office meetings, conference calls, more recently Zoom sessions, and eventually Netflix to wind down the day. Being pulled in a million directions at work, occupational busy-ness is a badge of honor, amplifying his marketplace salability, and possibly making him even more of a “man” - which is the ultimate goal.

The few attachments that Pakistani men unconditionally forge and ungrudgingly perform are blood ties; parents, siblings, their own children, maybe even a partner (although that isn’t necessarily a blood relation)

Now this isn’t always by choice, for there are obligations that must be met and bills that must be paid; nor is it all bad news, for being output driven and professionally committed suggests he will unlikely shirk responsibility and lapse into freeloader mode. In fact, the probability that he will come through at moments that matter is suspiciously high, for the Pakistani man knows when to pull out the benevolent, protective card. But the question becomes: as pivotal as it is to be there when a crisis erupts, should it be enough to get a clean chit for everything else that’s flouted?

Whatever of introspection, erecting companionship, bolstering friendships that don’t offer conventional returns on investment, but may be an end in themselves, without which most humans feel adrift?

The Pakistani man is in fact unique: rarely raised to explore, question, reconnoiter, even challenge the notion of friendship – particularly with the opposite sex – as a pursuit of mere platonic happiness that won’t tick any material or strategic boxes, such as marriage. They are mostly absorbed in taking themselves too seriously, meticulously planning ahead, other times absorbed in a mindless passing of time, as long as it doesn’t demand reflective energy and thought, oblivious to the possibilities of drawing meaningful human connection.

The majority of my handful of close friends and confidantes are Pakistani men and there is much to be celebrated about them. What’s more corrosive and frustrating, however, is the large brand of Pakistani men that purposefully reject the quest for self-discovery

Although social and political awareness for most Pakistani men is limited to news and social media, occasionally, you’ll stumble upon one who will surprise you with his creative fibre and rustic humour; initially, you’ll find it appealing. He’ll relish your access to the unguarded world, tap into your flaws and anxieties, examine books and ideas, culture and travelogues with you — even welcome your proclivity to speak your twisted mind, stir emotions and polemics – turning on its head the common myth that Pakistani men prefer girls who are seen and not heard; visually attractive but muted women. For a while you’ll believe he is willing to invest in the exchanges and connection, live life in all its dimensions, and go along.

Unfortunately, though, years of socialization and chains that he has forged around himself won’t let the magic hold, and disappointment will quickly set in. A manic daily routine, fragile egos, latent insecurities, even boredom may set in. The Pakistani man wants to witness tangible scores and outcomes to this giant friendship experiment he has hurled himself into. As a woman, therefore, you are constantly under fear of friendship attrition, strained by the pressures of inventing spanking new ways of keeping your Pakistani friend hooked and at the center. It can become grueling, mirroring some kind of work mandate with clearly stated benchmarks and targets that must be met to ward off the threat of lay-off. That was never the point, was it? Isn’t that what differentiated friendships from tactical transactions in the first place? Eventually, when it starts eroding, the loss to you will feel literal – a collapsing alliance that was carefully yet naturally curating – but also abstract: the loss of your belief in rapport, and solidarity, of a coalition that felt possible between good friends.

The few attachments that Pakistani men unconditionally forge and ungrudgingly perform are blood ties; parents, siblings, their own children, maybe even a partner (although that isn’t necessarily a blood relation). Holding on to your family’s apron strings, whilst occasionally frustrating, is honorable and something to preserve over generations. It produces a rich tapestry of culture and tradition, differentiating us from the West. But why the emotional quotient and desire to devote must saturate as soon as Pakistani men leave familial parameters appears less intuitive.

Of course, there is the back story of the obsession with masculinity, of having to appear in control at all times, with no room to express vulnerability or dependency, especially not neediness toward a female friend. There’s also a mindset spurred by hardheaded rationality, general reluctance to invest time, and an inability to appreciate the more elusive aspects of “what’s in it for them”; in other words, unless the benefits of a friendship are hitting hard in the face or brought as proof in a hand basket, it’ll be a tough sell to a Pakistani man.

This might be a good moment to clarify that I’m not a firebrand feminist whose mantra rests on male bashing. On the contrary, I depart from many assorted brands of women’s lib in Pakistan, masquerading as feminism, and find them thorny, cloned from western counterparts and unsatisfying. I’m also not a gender labeler, looking to caricature all Pakistani men as one indistinguishable lot. I don’t think I’m mad at men either, because anger, whilst potentially constructive, is rarely enough on its own. Perhaps I’m bewildered and somewhat disillusioned.

The majority of my handful of close friends and confidantes are Pakistani men and there is much to be celebrated about them. What’s more corrosive and frustrating, however, is the large brand of Pakistani men that purposefully reject the quest for self-discovery, to develop the capacity to understand first themselves and then another, spend energies constructing camaraderie, express spontaneously and sensitively, and realize that occasionally surrendering to vulnerability and free emotion doesn’t detract from manliness and appeal. To try and seek out those who believe that a life exists beyond corporate corridors and reaping professional rewards, one that is filled with expectation and wonder, and conversations which may not yield immediate gratification in the form of fiscal spur but may light up a dull, self-isolating evening, yielding deferred sentimental purchase. That to become a “WhatsApp person” to sustain such a friendship may be worthwhile after all.

I think these things often, hope for them to change, but cannot help asking whether, in a society where men are yet to be negatively sanctioned for side-stepping domestic duties and childcare, where the common male ego-led logic is never to lose an argument but instead, lose a friend, where days and nights are spent figuring out one’s mark-to-market worth, my expectation is premature and misplaced. That for now, perhaps, unearthing the topsoil and repurposing Pakistani men, their life and ambitions, towards discovering curiosity, companionship and consistency, sparking the realization that time doesn’t always have to mean money, must remain a dream deferred.

Saba Karim is an Instructor at New York University’s campus in Abu Dhabi and author of the forthcoming novel, Skyfall