History isn’t kind, especially in Pakistan where you have elements based on rational thought applied in a nation with a very culturally steeped thought process. This immediately colours any interpretation of history through the lens of the experience that is shaped by the mentality rooted in any particular party of the country.

Iskander Mirza belonged to the Najafi dynasty. His ancestor Sayyid Husain Najafi migrated to India at the invitation of Emperor Aurangzeb Alamgir where he settled in Delhi in 1676.

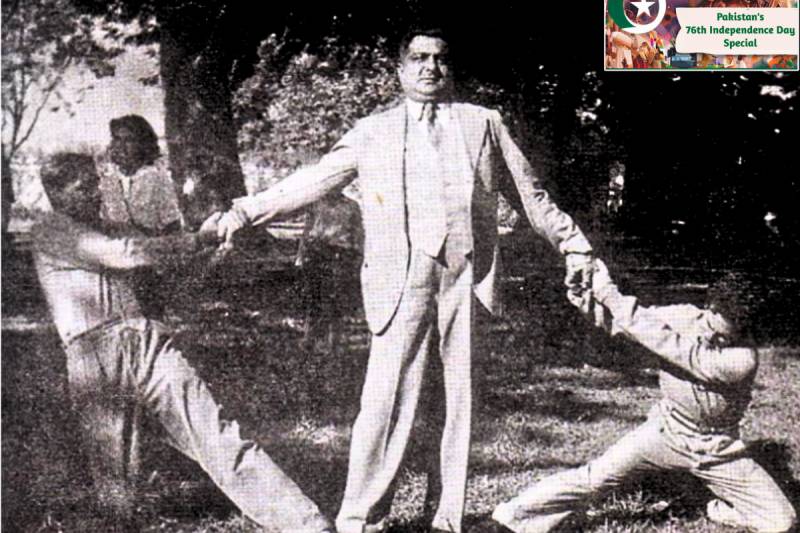

In 1926 having joined the Indian Civil Service Mirza went on to serve in what was then referred to North West Frontier (modern day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in Pakistan). He later on became Governor of East Pakistan and succeeded Ghulam Muhammad as Governor-General. From March 23, 1956 – October 26, 1958 he served as President of Pakistan.

In his memoirs compiled by Syed Khawar Mehdi, Mirza documents his life and career in a clear cut manner. There is no self glorification nor is there any element of playing the victim card but he does explain his decisions. This was a man who conducted himself to the best of not just abilities but with the dignity of carrying a rich family legacy and with the clarity of purpose.

Most interesting are his interactions with the Quaid-e-Azam, Muhammad Ali Jinnah as it shows the thought process of two men who seeked to serve the newly established Pakistan. To see the varying experiences of a lawyer and a military man as they navigate the world of politics is a lesson on how far low we as a nation have fallen given the calibre of decision makers today.

This is also precisely why Iskander Mirza remained undefended all these years till now. Fearing attacks from a system headed by those who prefer the truth remains untold, all of Mirza’s diaries, personal papers and belongings vanished as per General Ayub Khan’s orders. And that was the end of Mirza’s voice, the last remaining presence he had in Pakistan as himself.

Coming across his memoirs, Syed Khawar Mehdi realised the gross injustice and embarked on a five year journey in which he pieced together a research that backed Mirza’s own story that risked being buried completely in the sands of times. Mirza had started working on his memoirs post retirement in London after the publication of Friends Not Masters by Field Marshal Ayub Khan. By 1969 an incomplete account had been put together but due to poor health he was unable to complete it.

The amount of effort gone into backing up the memoirs show in two sections. The first is the interview conducted by legislator and diplomat Mirza Abul Hassan Ispahani and the second is the section documenting the Gwadar papers which detail Mirza’s role in the acquisition of Gwadar.

In the interview, Mirza offers a window into his thought process especially on decisions which may be seen as ways of keeping the show together when elements around him floundered and flustered while holding positions of powers.

When asked about his role in the one-unit formation or why he kept changing prime ministers, Mirza’s clarity is astonishing. It is evident the man was not thinking of himself but in fact was astute enough to realise the implications of decisions that were not to be made but without the foundation of rationality, a clean cut away from the murky decision-making Pakistan experiences now.

The Gwadar papers importance cannot be stated enough. Gwadar was officially purchased by Pakistan on September 8 1958 and after 174 years of Oman’s rule, it became part of Pakistan.

“Iskander Mirza’s strong-armed diplomacy along with the able guidance of Prime Minister Sir Firoz Khan Noon’s government throughout the acquisition process was instrumental in achieving the desired results. It was the only time since the initial accession of the princely states in 1947-8 that Pakistan’s territory had increased,” writes Mehdi (pg. 215).

“Unfortunately, history as scribed by the State and its retainers made sure to understate President Mirza’s contributions through callous censorship, and his role in the Gwadar acquisition became one of the many casualties.” (pg. 216).

This lack of acknowledgement and appreciation of Mirza’s efforts are painstakingly traced by Mehdi as he documents the US-China rivalry. Despite apprehension on the part of the US, Mirza reassured the US Pakistan would honour all treaties signed and travelled to China. But as Mehdi notes, “in a declassified confidential cable dated 17 May 1956 from the Chinese Embassy in Pakistan… it is obvious that President Iskander Mirza’s strategic overture to China was not looked kindly upon by the much disappointed American media.” (pg.218)

While many in today’s Pakistan will jump to conclusions depending on where they stand on the political spectrum, what remains to be understood is that Mirza was not acting in a personal capacity. The fact he understood the need to appease the US and yet the necessity of engaging with China indicates he realised the need to act in the country’s interests and uphold Pakistan’s sovereignty that as Mehdi notes, “ruled supreme in his policies and obvious in his statements.”

Were the seeds of discontent with Mirza? It is most likely so.

In the letter to The Times on Ayub Khan’s book, Mirza writes: “If I had harboured any self-interest, would I have initiated the Revolution?... My cardinal error was that I trusted persons whom I know and helped, for twenty years; I regarded them as reliable and trustworthy friends.”

Pakistanis need no external enemies. We have plenty of our in our own country. At least one friend who was wronged can now finally rest in peace knowing he did have the final say.