The year 2019 presented opposition forces in Pakistan a unique opportunity for making good on their claim that they would offer some sort of vigorous resistance to a regime that dominates the political landscape. The opposition said much to call into question the legitimacy of the current ruling dispensation. And yet, the year proved to be a period of constant capitulation.

Conditions seemed ripe for a narrative of resistance.

First, the aforementioned issue of legitimacy. The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) came to power through an election which was “heavily rigged,” claimed opposition parties, as they came together under an alliance convened by Maulana Fazal-ur-Rehman of the JUI-F. A weak coalition held the centre and opposition parties are well represented in the halls of power.

Second, there was the question of competence. The newly installed government led by the PTI appears to have made it a point to flounder on all core areas of governance and policy – inspiring little confidence in the public and in international markets. A year-and-a-half of PTI’s rule was enough for the public to realize that Naya Pakistan was more of the old, except perhaps even more dysfunctional.

Third, there was the distinctly vicious nature of the ruling regime: space for human rights defenders continued to shrink, political opponents were shown no mercy in the name of accountability, critical voices in the media were silenced and the government appeared deaf to the plight of common citizens as the economy nosedived.

Despite glaring differences in their strategies – such as on the question of joining the Parliament or taking to the streets – the Opposition Alliance came together on a common minimum alliance of resistance to a government which they deemed unfit to govern. The alliance had two fresh faces leading the cause on behalf of Pakistan People’s Party and Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) and it appeared poised to push back for the space lost in the years leading to the general election in 2018.

Maryam Nawaz and Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, with their respective parties beleaguered under the baggage of their fathers’ politics, evoked the hope of a fresh attempt to resist the creeping authoritarianism capturing state and society. Maryam Nawaz caught public imagination by presenting herself as the head of the largest party in the Punjab fighting for civilian supremacy. She began drawing large crowds to her rallies, even as she was in and out of prison. Bilawal, despite being under constant attack for the PPP’s disastrous tenure between 2008 and 2013, also gained popularity as a young leader in the National Assembly. His provocative speeches in the Parliament and at his rallies sustained the nostalgia among PPP loyalists for resistance to an undemocratic regime as espoused by his mother, Benazir Bhutto.

Yet, despite their best intentions, harsh words and big demonstrations, the Opposition Alliance was unable to make any significant gains in the struggle for democracy and civilian supremacy. First, it failed to remove the Senate chairman in a vote of no confidence. Then in November, after a year-long mobilization, Maulana Fazal-ur-Rehman staged a sit in Islamabad with thousands of his supporters to press for Imran Khan’s resignation. He was backed halfheartedly by his allies in Opposition and after spending a few days negotiating with the government, called off his protest. The Maulana said his party would shift to Plan B of its strategy, but this, too, disappeared from the discourse. It was said that there was an attempt from within the unelected institutions of state to dismantle the pillars of Imran Khan’s regime – this is why Chief Justice Khosa’s intervention on the question of the army chief’s extension surprised many people and the issue was the subject of great debate and discussion across the country. The government secured time to legislate on this issue and this piece of legislation is looking to be the main source of drama in high politics over the next few months.

Meanwhile, the Opposition Alliance seems to have run out of ideas.

Now that it is settled in power, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf is a party of the status quo. It is no longer the dark horse in the running. People have now experienced what it is like to be governed by Imran Khan. Those disappointed by his dismal performance will inevitably seek an alternative, a new force to fill the vacuum created by the absence of a pro-people opposition.

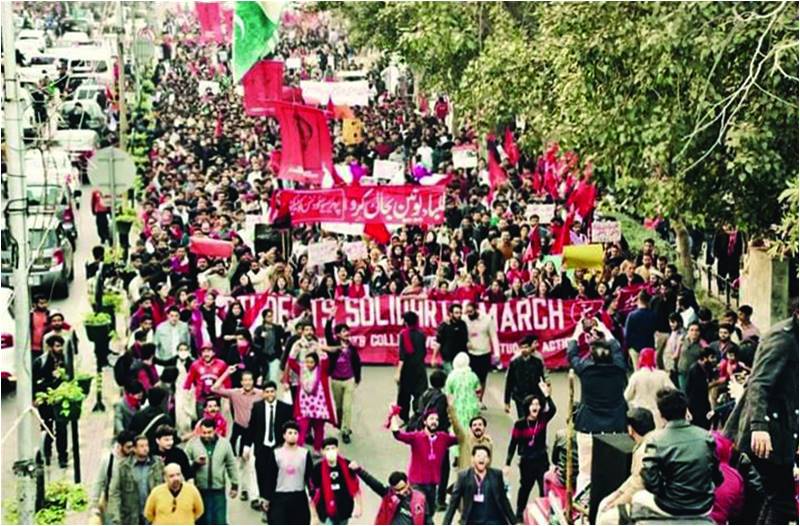

This desire for something new can already be witnessed in the swelling crowds of marches for constitutional rights held across the country over the past year. Currently, these marches are being organized by movements and collectives, in fragments, but with increasing cohesion. These movements and collectives have also faced repression in the form of murders, arrests, and abductions of activists over the last one year. Yet despite the crackdowns and periods of retreat, these movements gained strength in discourse and on the streets. It is clear that a new force is simmering under the surface and waiting to take form.

And this, perhaps, is the saving grace from 2019; that the new decade heralds an opening for new forms of popular politics to take shape. Can we not dare to hope that if the forms of authoritarianism are changing, so can the politics of resistance?

The writer is TFT News Editor and can be contacted on Twitter @aimamk

Conditions seemed ripe for a narrative of resistance.

First, the aforementioned issue of legitimacy. The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) came to power through an election which was “heavily rigged,” claimed opposition parties, as they came together under an alliance convened by Maulana Fazal-ur-Rehman of the JUI-F. A weak coalition held the centre and opposition parties are well represented in the halls of power.

Second, there was the question of competence. The newly installed government led by the PTI appears to have made it a point to flounder on all core areas of governance and policy – inspiring little confidence in the public and in international markets. A year-and-a-half of PTI’s rule was enough for the public to realize that Naya Pakistan was more of the old, except perhaps even more dysfunctional.

Third, there was the distinctly vicious nature of the ruling regime: space for human rights defenders continued to shrink, political opponents were shown no mercy in the name of accountability, critical voices in the media were silenced and the government appeared deaf to the plight of common citizens as the economy nosedived.

Despite glaring differences in their strategies – such as on the question of joining the Parliament or taking to the streets – the Opposition Alliance came together on a common minimum alliance of resistance to a government which they deemed unfit to govern. The alliance had two fresh faces leading the cause on behalf of Pakistan People’s Party and Pakistan Muslim League (Nawaz) and it appeared poised to push back for the space lost in the years leading to the general election in 2018.

Maryam Nawaz and Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, with their respective parties beleaguered under the baggage of their fathers’ politics, evoked the hope of a fresh attempt to resist the creeping authoritarianism capturing state and society. Maryam Nawaz caught public imagination by presenting herself as the head of the largest party in the Punjab fighting for civilian supremacy. She began drawing large crowds to her rallies, even as she was in and out of prison. Bilawal, despite being under constant attack for the PPP’s disastrous tenure between 2008 and 2013, also gained popularity as a young leader in the National Assembly. His provocative speeches in the Parliament and at his rallies sustained the nostalgia among PPP loyalists for resistance to an undemocratic regime as espoused by his mother, Benazir Bhutto.

Yet, despite their best intentions, harsh words and big demonstrations, the Opposition Alliance was unable to make any significant gains in the struggle for democracy and civilian supremacy. First, it failed to remove the Senate chairman in a vote of no confidence. Then in November, after a year-long mobilization, Maulana Fazal-ur-Rehman staged a sit in Islamabad with thousands of his supporters to press for Imran Khan’s resignation. He was backed halfheartedly by his allies in Opposition and after spending a few days negotiating with the government, called off his protest. The Maulana said his party would shift to Plan B of its strategy, but this, too, disappeared from the discourse. It was said that there was an attempt from within the unelected institutions of state to dismantle the pillars of Imran Khan’s regime – this is why Chief Justice Khosa’s intervention on the question of the army chief’s extension surprised many people and the issue was the subject of great debate and discussion across the country. The government secured time to legislate on this issue and this piece of legislation is looking to be the main source of drama in high politics over the next few months.

Meanwhile, the Opposition Alliance seems to have run out of ideas.

Now that it is settled in power, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf is a party of the status quo. It is no longer the dark horse in the running. People have now experienced what it is like to be governed by Imran Khan. Those disappointed by his dismal performance will inevitably seek an alternative, a new force to fill the vacuum created by the absence of a pro-people opposition.

This desire for something new can already be witnessed in the swelling crowds of marches for constitutional rights held across the country over the past year. Currently, these marches are being organized by movements and collectives, in fragments, but with increasing cohesion. These movements and collectives have also faced repression in the form of murders, arrests, and abductions of activists over the last one year. Yet despite the crackdowns and periods of retreat, these movements gained strength in discourse and on the streets. It is clear that a new force is simmering under the surface and waiting to take form.

And this, perhaps, is the saving grace from 2019; that the new decade heralds an opening for new forms of popular politics to take shape. Can we not dare to hope that if the forms of authoritarianism are changing, so can the politics of resistance?

The writer is TFT News Editor and can be contacted on Twitter @aimamk