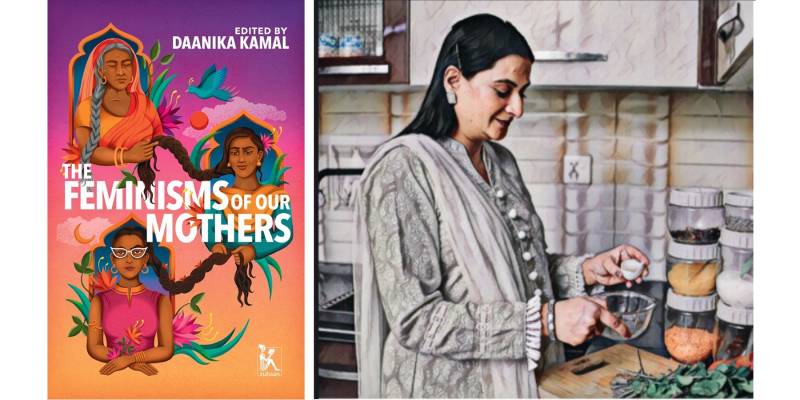

Feminisms of our mothers explores the intergenerational feminisms passed to Pakistani women through their mothers and grandmothers. Daanika Kamal is a researcher and writer from Karachi who is currently based in London, where she is completing a PhD in Law. The book starts with a preface by Daanika in which she explores how women are often compared to their mothers and spend our childhood trying to carve out identities different from our mother. As adults, we return to the very identities we tried to pull away from as children. Though some of our mothers may not refer to themselves as feminist, differing from their daughters about how the label should be interpreted perhaps, yet Daanika states that the subtleties of our mothers’ adaptabilities are centred on women’s empowerment. And situated among these subtleties are the movements of consciousness and self-determination that we as daughters navigate through as we form our own idea of what feminism is today.

The anthology starts with Maham Javaid’s essay, “What my mother taught me.” In it, she describes how happy her mother was when she was pregnant with her. Maham writes that like Ismet Chughtai’s Bi Amma, her mother always finds a way to create room where none exists. She is incapable of not wishing the best for Maham, even when Maham is her worst to her. Her love is endless, without an end in sight, deeper than darkness, wider than the world itself and undoubtedly corroded by the patriarchy that seeps into us all. Maham describes how embroidering tulips into lawn is the first thing she remembers her mother teaching her. Maham writes that when she looks around her home, her pantry is arranged as neatly as her mother’s, she drapes her shawl in the exact shabby way as her mother does and she saves the same way as her mother by buying only what she must.

Her mother taught her how to talk, sit, eat, think and love just by doing all those things. She writes that maybe sometimes that kind of love can be dangerous, but it can be radical, brave and full of hope.

The second essay is by Maria Amir, “All the women in me are on fire.” She discusses in the essay that women are perpetually trying to be regarded as the people we are, rather than a population that takes up half the planet and holds it firmly within its fragile grasp. Maria writes that the entire world is built upon a woman’s strength, which is perpetually defined in opposition to that of men. She says that the shape of male strength is muscle, bluster and power – ours must always be a response to those things. Maria says she resents the expression ‘strong woman.’ She feels that all women are strong and all women are survivors: “Some survive silently, some fight, some manoeuvre, some negotiate, but they are all strong […] We revere women who don’t fight back and take all of life’s blows, literal and metaphorical, in silence.” As women we are expected to compartmentalize our rage or else, we are met with the phenomenon of “log kiya kahenge?”

The third essay is by Zoya Rehman, titled “When they suffocate.” She describes how her mother was physically abusive towards her till finally she rebelled and asked her to stop. She feels she was a living reminder to her mother of everything that was wrong in her life: her failed dreams, her failed marriage, her failing mental health and her failure as a mother. Zoya writes that at best, her mother is a decent person who has been wronged by life, and at worst, she is her tormentor. Over the course of their relationship, Zoya’s mother seems to have forgotten how abusive she was towards her – selective amnesia being her way of dealing with Zoya’s resentment. Zoya asks pertinent questions: “What happens when daughters are badtameez; when they talk and write back while sometimes rejecting the transactional nature of their mother’s love, their disappointment mixed with revulsion?” For Zoya, her mother isn’t even her primary family when she visits her hometown: such are the complicated dynamics of mother-daughter, yet their relationship is the feminist space that she will always hold hope for.

The fourth essay is titled “(Un)mothering” by Tooba Syed. Tooba claims that the precise negotiation that our mothers and grandmothers made to survive their patriarchal homes became their first encounter with their struggle with patriarchy and this is why she needs to write about the mothers in her life. She writes that: “Mothering is continuous, fluid, non-linear and lifelong. The is never-ending and ever-beginning.” She describes Anwar Sultana, Rukkiyya Bibi and Ismet Sultana all raging at her from their graves, mothers who had led their lives struggling. She describes her Khala who was thought of as ‘mad’ even though she mothered her children as best as she could. She describes that a woman’s care labour was essential to the house and her Khala understood that when she once spoke of her hands being ugly as a teenage girl. Her Khala told her that these are what hands of workers look like, and that she should be proud of them. “Women are selfish and sacrificing, loving and alienating, mothering and unmothering – there are multitudes of ways to be a woman.” Our mothers and grandmothers survived domesticity but also avoided it – sometimes through silence and at other times through madness. No story of motherhood is homogenous.

The fifth essay “Peroun ki beriyan” is written by Amna Shafqat and Mariam Shafqat. In it, they write of how their mother’s feminism back in the day was her refusal to buy them local digest magazines which sold Cinderella stories of a girl getting married and living happily ever after. The sisters believe that they have inherited their mother’s perseverance. Their mother did not teach them to dream half-dreams and for that they are grateful to her.

Each essay in the collection tells the tale of the author’s relationship with their mothers and sometimes grandmothers and aunts. The essays deal with the intersectionality of gender and they explain that feminism comes from removing ourselves from binary structures that society is immersed in. Moreover, the essays deal with how women cope with care labour and being working women as well. One explains how working women are often looked down upon, and how women who are homemakers are thought to be safe while working women are thought to be unsafe.

Aiman Rizvi ends the anthology with her essay, “Feminist vernaculars, feminist lies” that the worst lie that feminism told her was that of community, even though there is a feminist community to which she belongs. She questions whether such a community truly exists even with the Aurat March taking place regularly. She claims that too many truths about the performative nature of their protest have been spoken and says that: “[…] when your enemy pervades the nooks and crannies of your everyday, everywhere – when your enemy evades clear identification, but just is, in everything; you seek a home and shelter in your means to fight back.”

Women are mothers, daughters-in-law, grandmothers, daughters, wives, aunts, workers, they are the cement that keeps our society together and this is what this book of essays teaches us. They bear the emotional and sometimes physical scars that society throws at them with grace. Women are what make the world go around with their labour and kindness.