It is 2023, and the conditions of the flood affected population in Balochistan continue to remain critical. I have been involved in fundraising since July 2022, and the need for relief and aid hasn’t let up.

I imagined, hoped, and expected that the government would step in at some point, but it’s been 7 months, and they have not done so sufficiently.

Don’t tell me it’s about a lack of resources. Where they think it’s a priority, money is poured in - we can all see that.

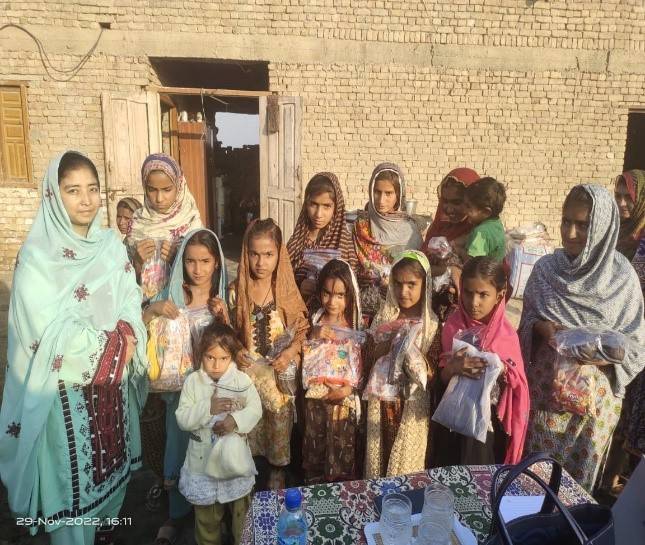

Source: Author

In one of the most affected villages in Jaffrabad district, Wazir Abad Abro, UC Cattle Farm, we went to speak to Shumaila. Shumaila is a gorgeous 10 year-old girl. She was in the second grade before the rains came crashing down and turned her little world upside down.

Shumaila lives with her parents, Mohammad Athar and Rehana, and twelve siblings. Her generation will be the first to be literate and educated if they have the opportunity. From anecdotal observation, it seemed that no one above the age of 30 was literate in this village. Although poor and vulnerable by any standards, Shumaila was happy in her former life. Her mud home housed all of them - now that seems like a distant dream.

Wazir Abad Abro is about 30 kilometers from Jaffrabad town. UC Cattle farm is in fact owned by the government. Everyone who lives here is dependent on agriculture and livestock. Everyone is a tenant of the government.

The Government is the custodian of all the land, while the residents have been here for generations. Folks earn a living by either managing government owned livestock, along with some of their own animals, or are tenant farmers, which means they grow and cultivate wheat and rice for the government. There is no concept of rent, or long-term contractual tenancy agreements; rather a traditional pattern of barter payments, where the tenant is responsible for all input costs for sowing the land or livestock management, while the outputs or dividends are divided half and half between the government and the tenant, at the end of the year or growing season. All risks associated with this work are borne by the tenant. The land management patterns in these parts, like the rest of Pakistan, are stacked up against the unskilled, non-literate, vulnerable tenant, or bonded laborer.

Shumaila’s family like the rest of the villagers, are extremely poor and continue to remain food insecure, shelter less, and vulnerable in all basic needs, after the rains and floods of 2022.

Source: Author

Too many stories of this humanitarian crisis have been from the perspective of adults; I was keen to listen to the ordeal from a child’s perspective. Let’s not forget a massive percentage of Pakistanis are underaged minors. In Balochistan, the average family has 8 children.

The state has not seen fit to provide education, housing, health facilities and basic human settlement needs for its citizens even when they live on public lands.

Shumaila narrated the harrowing experience of uninterrupted rain which destroyed her mud home. Her seven brothers and five sisters were cramped in a couple of rooms, along with her parents. The family decided to escape the deluge by leaving their village and moving to higher ground nearer to the town center. The lake nearby had overflown and there was water everywhere. Unlike some adults, Shumaila had never experienced the impact of floods or rains in her life. The traumatic experience is etched in her mind.

It’s been a couple of months since Shumaila and her family returned to their village. Although they live on government land, there remains no security of tenancy. Therefore, the stress of returning to their village was paramount on her parent’s minds. Her family has lived here for 80 years and yet, in a second they could be displaced.

When we asked Shumaila what she missed the most, without hesitation she wished to return to school and play with her friends. She dreams of becoming a teacher.

My heart ached watching her face, not because it reflected a commendable desire, but because the look in her eyes indicated that it could very well end up being a far-fetched dream. Her love for books was obvious. The floods destroyed all her crayons, books, pencils, and beloved school bag. Her father promised her to get all these things when they returned home.

Now that they have, he told her, as a laborer, and so many expenses to bare, there is little money to buy books and school supplies. The expectation is that some NGO or charitable organization will provide school needs.

The state has not seen fit to provide education, housing, health facilities and basic human settlement needs for its citizens even when they live on public lands. How many legal constitutional violations is that, I wonder?

Aside from the morality of this tragedy, I wonder if this is acceptable legally. We conveniently shove morality and piety down everyone’s throats, but when it comes to providing basic human rights and dignity for our citizens, every person is on their own.

I wonder to myself - the government owns this land but does not see the need to ensure that Article 26 is enforced on public lands. Frankly, what does government owned land even mean? What purpose does the government own land for? Why haven’t they distributed it to these generational tenants and invested in the area with good schools and health facilities.

I also wonder if the government will build disaster risk management and resilience systems here. Where are the low-income housing schemes where they are needed most?

The area is the breadbasket of the province; there is water aplenty, fertile land aplenty and yet, the residents are malnourished and deprived of the very basics. Who is responsible?

With trepidation, I asked Shumaila about her experience of the rains of 2022; I could see her shudder as she recounted what happened in the fateful months from July to October. She was so scared; the sound of the heavy rain was endless for over 30 days. All the homes in her village were adobe houses. One by one, they collapsed into a pile of mud.

Their home, hearth and security – all crumbled in front of her eyes. The family remained by the roadside for 20 days with many of their neighbors. Fear was what Shumaila remembers. She was constantly scared.

For 20 days, they ate when charity was provided by random passersby. She remembers that they had black tea and naan twice a day unless some random charity was provided. When I asked about her regular diet, she said, we don’t eat meat, only on Eid. She loved the taste of meat, but they couldn’t afford it. Naan, or rice and tea, with some vegetables is their staple diet. If they can have this twice a day, they are grateful.

Listening to her, I thought to myself that the area is the breadbasket of the province; there is water aplenty, fertile land aplenty and yet, the residents are malnourished and deprived of the very basics. Who is responsible?

Listening to Shumaila and all her friends, it was apparent that they were malnourished, and now I understood why.

She remembers being sick during their ordeal by the roadside. Many in her village had similar stories. Everyone in the village had malaria and several other gastro and skin infections.

Sitting in the makeshift house, Shumaila was looking forward to going back to school, when it begins, and keen to have at least a roof over her head. Her happy go lucky demeanor was incredible, despite her harrowing experience.

We asked her what she would wish for if she had three wishes. “I wish for new books and a school bag. My second wish is to have a home which does not fall down again. Finally, I hope I can study and become a teacher one day.”

I asked her what her favorite thing was? “My favorite thing is to be able to have a meaty meal cooked by mom. I also love the dress and shoes you have just given me.”

Areas most heavily affected by the floods are primarily on lands owned by large landowners. They are called feudal landlords because of the traditional patterns of land management; where the landlord determines all the rules of engagement, with very little in return for the tenant other than ‘protection’ and permission to ‘live on their lands’. Typical tenants are residents on the land, in exchange for labour, to sow crops, and to manage livestock - for a pittance, or in kind. It is rare that tenants are paid for their services. There is no health care or education provided, or pensions or social security. Moreover, the risk of livestock dying of disease, lack of fodder, starvation, heat, flooding, or any other calamity is borne by the tenant; the same applies to the crops.

It does not make any sense for landowners to continue to own the land and reap the benefits, without assuming any responsibly for the vulnerable souls who live and toil on it.

In my relief work in Balochistan, I have aided flood affectees irrespective of land ownership patterns. In the rebuilding phase of relief interventions, I intend to aid only those who either own their land or have secured tenancy. I realized from my work in these areas that this is going to be a challenge.

I strongly believe that those who own the land – feudal landlords, or the government - should be made responsible for the costs of rebuilding and providing dignified community infrastructure for these citizens of Pakistan. If they are unable, then the ownership patterns also need to change. It does not make any sense for landowners to continue to own the land and reap the benefits, without assuming any responsibly for the vulnerable souls who live and toil on it.

Take another example, in Ali Faqir village in Union Council Judhair, in District Jaffrabad, approximately 50 kilometers from Jaffarabad. Everyone here is a tenant of a single landlord. Tenants are allowed to live on the land if they look after the large landlord’s livestock and cultivate his crops. There is nothing wrong with this. But do they earn enough to feed themselves, their children and other basic needs?

The answer is no. Who is responsible for the welfare and wellbeing of these people?

The traditional pattern of ‘contract’ between the landlord and the tenants is the same as the above; the tenant spends on inputs and bares the risk for the cultivation while the landlord receives 50% of the crop.

There is no security as such, of tenancy or insurance for livestock or crops. Although they have lived on these lands for generations, they can be forcibly evicted at the will of the landlord. There are no legal systems in place to assist these Pakistanis.

We spoke to Zahoor, aged 12. Zahoor is physically disabled; he has no arms, while his weak legs are not strong enough to hold his weight. I inquired about what happened to him. No one had any answers. Perhaps a combination of nutritional deficits, polio, or genetics. Nevertheless, he is unable to walk to school, which is several kilometers away from the village. Zahoor has three sisters and a brother. I think the disability could be genetic since two of his siblings are also challenged. We have noted this as a common ailment in many of the affected population in the Naseerabad division. Perhaps it is nutrition related, or due to children remaining unvaccinated or because of the tradition of marriages within the family.

Little Zahoor is illiterate but craves to learn. He watches some of the village children go to school and wishes that he could too. My heart just broke at the utter lack of opportunity for him, and so many others like him here.

We spoke to Zahoor’s parents, Jagan and Zeenat. Jagan is unwell too, and was in his bed lying down while we spoke to him. He seemed to be depressed and perhaps also physically disabled. Zeenat manages the home single handedly.

Source: Author

Little Zahoor is illiterate but craves to learn. He watches some of the village children go to school and wishes that he could too. My heart just broke at the utter lack of opportunity for him, and so many others like him here.

How is this even allowed in Pakistan? How does the state and its managers allow this to continue? The cruelty and human cost are harrowing.

The only source of support for Zahoor’s family is charity from his grandfather, which is waning as times goes by. His support literally only covers food expenses.

No one in this family that we saw – across three generations - can read or write.

Throughout my relief work, my interaction has primarily been with adults. I saw so many children in the medical camps, and therefore, I was very keen to speak and hear from the children who have suffered through this disaster.

I spoke to Zahoor about the recent rains in July 2022. Like so many children I spoke to, fear was what they felt the most. “I was so scared because the water seemed to come down forever.” Zahoor was even more scared than most because “when the village decided to relocate, I was even more worried because everyone in my family is disabled, bar my mother and one sibling. My mother and my grandfather helped us to move. I can’t tell you how scared I was.”

Listening to him brought tears to my eyes. There are no rescue services here. No civil defense here. No ambulances.

What do we spend on? What should we spend on in Pakistan?

"If I could have a strong house where I can feel safe, that would be nice.”

The constant feeling of insecurity from living in a makeshift camp for two months made Zahoor feel helpless. At least, everything and everyone was familiar in the village. When the family came back to Ali Faqir, he was relieved. What Zahoor remembers most is the fear of dying never leaving his side. His disability became even more acute, “I could not run from the water, which was everywhere, and all around me. I knew that I would die without help.”

Zahoor also contracted malaria along with the rest of his family while they were in the makeshift camps. All he remembers is the unending pain and crying; his grandfather carried him to a doctor who prescribed a few medicines, which helped a little.

I was so heartbroken listening to him; I changed the topic quickly.

“What is your favorite thing?” I ask him. “I like to eat yummy food like meat, and anything sweat like candies; we can’t afford them but sometimes I get some.”

All he craves for is his home, where he can feel he has some control over his own welfare. We asked him what he would like most, if he had three wishes? Zahoor looked down and said “I wish my legs were able. I want to play with my friends and be able to go to school. If I could have a strong house where I can feel safe, that would be nice.”