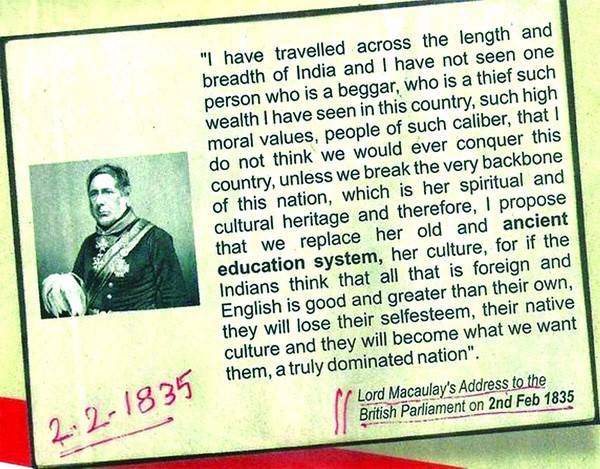

“I have travelled across the length and breadth of India and I have not seen one person who is a beggar, who is a thief. Such wealth I have seen in this country, such high moral values, people of such calibre, that I do not think we would ever conquer this country, unless we break the very backbone of this nation, which is her spiritual and cultural heritage, and, therefore, I propose that we replace her old and ancient education system, her culture, for if the Indians think that all that is foreign and English is good and greater than their own, they will lose their self-esteem, their native self-culture and they will become what we want them, a truly dominated nation.”

This was what Lord Macaulay stated in the British Parliament on February 2, 1835. The first time I heard this was from my exuberant friend who was more than interested in conspiracy theories and held that the Indian subcontinent would have been a superpower had the British not showed up. To be honest, it seemed that the Indian subcontinent had indeed been a bastion of happiness and progress until lord Macaulay came up with this devilish idea of destroying the ‘civil and cultural’ heritage in order to impose British rule upon us.

I’ve come across this reference to Macaulay’s speech many times, mostly by educated and well-intentioned individuals. Some time ago, a column in a leading Urdu newspaper caught my attention. It delved upon the same speech and also gave some unbelievable figures regarding the number of schools, remuneration of teachers, student-teacher ratio, etc. This got me to search a bit about the background and the speech itself. As it turned out, the speech attributed to Lord Macaulay is a hoax.

Lord Macaulay, as a member of the Council of India, did indeed address the Parliament on the February 2, 1835 regarding education in India, but the contents of his speech were completely different. Macaulay’s speech was primarily a reflection of his views on an Act of British Parliament (passed in 1813) which sought to set aside money for the promotion of scientific studies in India, and for a revival of ‘native literature’. Macaulay likened the revival of native literature (in Arabic and Sanskrit) to revival of ancient Egyptian knowledge based on hieroglyphs and superstitions, arguing that this particular aim does not merit the expenditure of British taxpayer money. Rather, for the intellectual development and improvement of the ‘natives’, he advocated the use of medium of English language through which science was to be taught in India. His belief in superiority of his native language over Arabic and Sanskrit was based on his conversations with experts of these languages and his own study of them. That led him to conclude that ‘a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia’. The tradition of poetry may have been well entrenched in India, but when it came to factual sciences (rather than imaginative works like poetry), the superiority of Europeans was well established in Macaulay’s mind.

For India’s development, he gave the example of Russia. According to him, the rise of Russia owed in large part to considerable contribution from a scientifically educated, westernised and liberal class. His lengthy speech had two other important points. The first concerned his idea of raising a ‘class’ of educated, westernised natives in India that would act as ‘interpreters’ between their British masters and its subjects. That class would later take the shape of Indian Civil Service (ICS), who not only became the ‘interpreters’ but also the ‘arbiters’ of the fate of hapless people of the subcontinent. In that way, Macaulay was the progenitor to the idea of the ICS. The second important point in his speech was the use of cost-benefit analysis of education expenditures by the British government. Quoting figures, he found it incredulous that the government would provide stipends to children for studying Arabic even though there was considerable interest shown by students towards studying English, and those who were already studying it were also paying for it. More the reason, he opined, for doing away with oriental languages and introducing English as a medium of study since its costs outweighed its benefits.

Now that the issue of his speech has been clarified, the question is that who spread this myth? It’s a long story, with no clear start point. But what is undeniable is that this myth started to take hold in the early days of RSS (the Hindu militant organisation), and was especially popular during many of Gandhi’s agitation movements. It gradually took hold of people’s imagination, despite facts that contradicted this propaganda. India, during the time of Macaulay’s travels, was never a unified country. Successive rebellions, wars and city-state rivalries had torn the society apart. Conditions really started to deteriorate after Aurangzeb’s death. It would suffice to say that these were not the mark of an educated society, rich in spiritual values and traditions that knit its people together.

If anything, the people of subcontinent should be thankful to Macaulay for what he did for its people. He tried to implement a system of education based upon scientific methodology rather than religion and mythology. The Indian Penal code has his indelible imprint on it, and he tried to keep his opinions free of personnel prejudices. His quotes regarding the local level of knowledge and prevalent languages may have been a bit harsh, but it should ideally be understood in the context of his ambitions. Our own ethical, moral institutions and practices afford us an opportunity to build our personnel lives and society, and Macaulay was careful enough not to disparage those. His verbal attack (if it can be labelled so) was aimed at the low (or non-existent) level of scientific knowledge and research in India of his time, and how to ameliorate it. His terse words and tone were probably demanded by the occasion of addressing the premier legislative institution of his nation.

This also brings to fore our appetite for conspiracy theories, and the never-ending quest to find a scapegoat for our problems. Myth upon myth has been fed to us through the distorted version of history that’s taught to us, through official propaganda, and fairy tales of the chattering classes. And like brainless dodo’s, we’ve enthusiastically gulped it down our throats. I am not sure when this fascination for conspiracy theories will end in Pakistan, but I can tell you that they’ve done tremendous damage to the national psyche (if there ever was one). As a proof, please get a hold of K.K Aziz’s Murder of History, which shall confound an individual’s senses once he or she realises that all we’ve been taught are lies and distortions. I will end by arguing that it’s time to banish this villainous ghost of Lord Macaulay, and to judge him according to facts rather than myths. This should be true of all individuals whose lives and works interest us.

This was what Lord Macaulay stated in the British Parliament on February 2, 1835. The first time I heard this was from my exuberant friend who was more than interested in conspiracy theories and held that the Indian subcontinent would have been a superpower had the British not showed up. To be honest, it seemed that the Indian subcontinent had indeed been a bastion of happiness and progress until lord Macaulay came up with this devilish idea of destroying the ‘civil and cultural’ heritage in order to impose British rule upon us.

India, during the time of Macaulay's travels, was never a unified country. Successive rebellions, wars and city-state rivalries had torn the society apart

I’ve come across this reference to Macaulay’s speech many times, mostly by educated and well-intentioned individuals. Some time ago, a column in a leading Urdu newspaper caught my attention. It delved upon the same speech and also gave some unbelievable figures regarding the number of schools, remuneration of teachers, student-teacher ratio, etc. This got me to search a bit about the background and the speech itself. As it turned out, the speech attributed to Lord Macaulay is a hoax.

Lord Macaulay, as a member of the Council of India, did indeed address the Parliament on the February 2, 1835 regarding education in India, but the contents of his speech were completely different. Macaulay’s speech was primarily a reflection of his views on an Act of British Parliament (passed in 1813) which sought to set aside money for the promotion of scientific studies in India, and for a revival of ‘native literature’. Macaulay likened the revival of native literature (in Arabic and Sanskrit) to revival of ancient Egyptian knowledge based on hieroglyphs and superstitions, arguing that this particular aim does not merit the expenditure of British taxpayer money. Rather, for the intellectual development and improvement of the ‘natives’, he advocated the use of medium of English language through which science was to be taught in India. His belief in superiority of his native language over Arabic and Sanskrit was based on his conversations with experts of these languages and his own study of them. That led him to conclude that ‘a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia’. The tradition of poetry may have been well entrenched in India, but when it came to factual sciences (rather than imaginative works like poetry), the superiority of Europeans was well established in Macaulay’s mind.

For India’s development, he gave the example of Russia. According to him, the rise of Russia owed in large part to considerable contribution from a scientifically educated, westernised and liberal class. His lengthy speech had two other important points. The first concerned his idea of raising a ‘class’ of educated, westernised natives in India that would act as ‘interpreters’ between their British masters and its subjects. That class would later take the shape of Indian Civil Service (ICS), who not only became the ‘interpreters’ but also the ‘arbiters’ of the fate of hapless people of the subcontinent. In that way, Macaulay was the progenitor to the idea of the ICS. The second important point in his speech was the use of cost-benefit analysis of education expenditures by the British government. Quoting figures, he found it incredulous that the government would provide stipends to children for studying Arabic even though there was considerable interest shown by students towards studying English, and those who were already studying it were also paying for it. More the reason, he opined, for doing away with oriental languages and introducing English as a medium of study since its costs outweighed its benefits.

Now that the issue of his speech has been clarified, the question is that who spread this myth? It’s a long story, with no clear start point. But what is undeniable is that this myth started to take hold in the early days of RSS (the Hindu militant organisation), and was especially popular during many of Gandhi’s agitation movements. It gradually took hold of people’s imagination, despite facts that contradicted this propaganda. India, during the time of Macaulay’s travels, was never a unified country. Successive rebellions, wars and city-state rivalries had torn the society apart. Conditions really started to deteriorate after Aurangzeb’s death. It would suffice to say that these were not the mark of an educated society, rich in spiritual values and traditions that knit its people together.

If anything, the people of subcontinent should be thankful to Macaulay for what he did for its people. He tried to implement a system of education based upon scientific methodology rather than religion and mythology. The Indian Penal code has his indelible imprint on it, and he tried to keep his opinions free of personnel prejudices. His quotes regarding the local level of knowledge and prevalent languages may have been a bit harsh, but it should ideally be understood in the context of his ambitions. Our own ethical, moral institutions and practices afford us an opportunity to build our personnel lives and society, and Macaulay was careful enough not to disparage those. His verbal attack (if it can be labelled so) was aimed at the low (or non-existent) level of scientific knowledge and research in India of his time, and how to ameliorate it. His terse words and tone were probably demanded by the occasion of addressing the premier legislative institution of his nation.

This also brings to fore our appetite for conspiracy theories, and the never-ending quest to find a scapegoat for our problems. Myth upon myth has been fed to us through the distorted version of history that’s taught to us, through official propaganda, and fairy tales of the chattering classes. And like brainless dodo’s, we’ve enthusiastically gulped it down our throats. I am not sure when this fascination for conspiracy theories will end in Pakistan, but I can tell you that they’ve done tremendous damage to the national psyche (if there ever was one). As a proof, please get a hold of K.K Aziz’s Murder of History, which shall confound an individual’s senses once he or she realises that all we’ve been taught are lies and distortions. I will end by arguing that it’s time to banish this villainous ghost of Lord Macaulay, and to judge him according to facts rather than myths. This should be true of all individuals whose lives and works interest us.