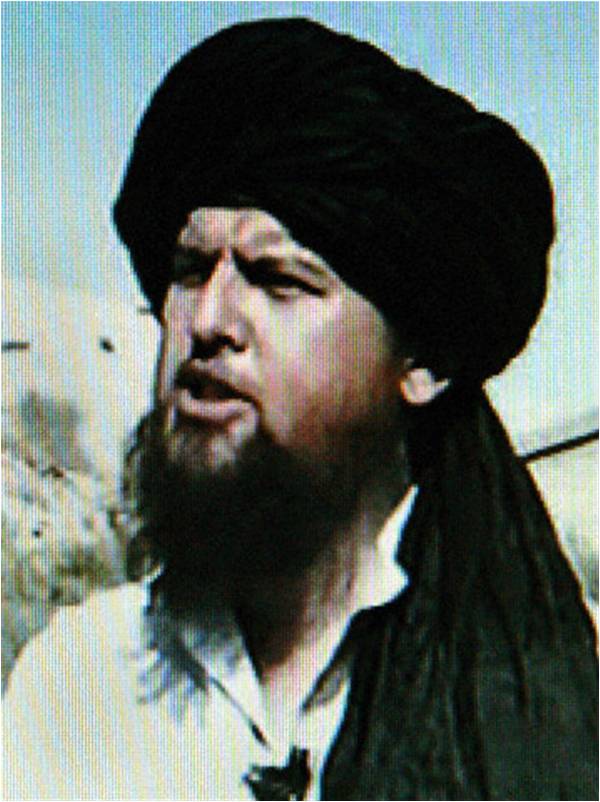

“Tahir Jan is dead.” A rumour about Tahir Yuldashev, amid a siege by the Pakistan Army and the FC, triggered a massive rebellion in the village of Kaloosha, South Waziristan in March 2004. What followed within hours was a bloody trail for the security forces between Jandola, the border that separates South Waziristan from the Tank Frontier Region, and the villages around Wana, the administrative headquarters of South Waziristan. Several dozen deaths in direct attacks and ambushes, loss of armoured vehicles and running battles with foreign militants resulted from this rumour, and though Yuldashev had escaped in the mid-night siege, this marked the beginning of Pakistan Army’s troubles at the hands of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU). Led by Yuldashev, an unknown number of IMU fighters had escaped to Waziristan following death of their founder Juma Namangani, an ethnic Uzbek from the Ferghana Valley and former Soviet paratrooper, in bombings by coalition troops in December 2001. Most of them arrived between December 2001 and January 2002 and settled down in Sheen Warsak, Azam Warsak, Kaloosha, and Wana, mostly living as paying guests.

I saw quite a few of them during my visit to Wana and these villages in April and June 2004. My hosts – the family of late Allah Noor, a journalist murdered in mysterious circumstances later that year, were also hosting some Uzbeks. He used to bemoan the fact that by dint of luck they got Uzbeks as guests. “They don’t have enough dollars, poor compared to Arabs,” he would say.

But as it turned out, the IMU grew in strength, enmeshing socio-culturally with locals and also increasingly radiating a radical world view that the Arab-African Al Qaeda stood for.

Apprehensive of the gradually shrinking space because of the army presence in the region, the IMU also began targeting security forces or their local allies, possibly deluded that they could get away with their brutal campaign. But the army’s patience ran out in March 2007 when it decided to take the bull by the horn; it embedded commandos in the private army of Mullah Nazir, then the mighty warlord representing Ahmedzai Wazir tribes. Within a few days, Nazir and the army evicted the Uzbeks and their local supporters, forcing them to find refuge with Baituallah Mehsud in areas such as Makeen, Ladha, Srarogha. When Baituallah founded the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) in December that year, it became a stronger socio-political cover for them, and they began partnering with TTP for attacks on security forces as well as funds-mobilization by supporting organized crime such as kidnappings for ransom and extortions.

[quote]Commandos were embedded in Mullah Nazir's private army to evict the Uzbeks and their local supporters[/quote]

Then came the year 2009, one of the deadliest in TTP-led violence. And the army decided to retake the Mehsud regions that the TTP had occupied since its creation.

“It is a do or die situation for [the Uzbeks] so they are scrambling for protection and would do anything for survival,” former Pakistan Army Chief of Staff, Gen Ashfaq Kayani, had told us during a briefing days before the October 17 military march on TTP strongholds. The Uzbeks have assumed a “wild card” status in a region where their safe space has gradually been shrinking, Kayani had said.

One of the major reasons for the 2007 and 2009 operations were the hundreds of tribal contacts and intelligence assets that the IMU in particular had executed for espionage, a task given to it by the TTP. The 2009 operation pushed the TTP and its Uzbek guests in to the mountainous terrain that separates North Waziristan from the South, many also sheltering with Hafiz Gul Bahadur.

In the month of May, the IMU became a target again, of a sustained aerial bombing campaign that left some 100 fighters dead, including Uzbeks and Chinese Uighurs who have been holding out in Sahwaal, Shaktoi, and adjacent areas. The reason: these foreign fighters had turned Waziristan into an Al Qaeda nest, and were using it for their terrorist operations against Pakistani and Chinese interests.

Their presence became unbearable also because it is no more compatible with the increasing Pakistan-China cooperation. The East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), for instance, openly vows to hurt Chinese interests wherever they are. And both the TTP as well as IMU supplement the ETIM agenda.

The origins of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan date back to the early 1990s, when Namangani joined forces with Tahir Yuldashev (variant Yuldosh), an unofficial mullah and head of the Adolat (Justice) Party, with the aim to implement Sharia law in the city of Namangan in Uzbekistan’s part of the Ferghana Valley. The government banned the Adolat Party in March 1992. A period of repression followed, forcing many Islamic militants to flee the Ferghana Valley. Namangani fled to Tajikistan, where he participated in the Tajik Civil War and established a base for his fighters in that country. Yuldashev travelled to Afghanistan, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, establishing links with other Islamic militants. He also made clandestine trips to Uzbekistan, maintaining contact with his supporters and setting up underground cells.

Their stated goal, as posted on the internet in August 1999, is the ‘establishment of an Islamic state with the application of the Sharia’ in Uzbekistan.

The IMU expanded its territorial focus to encompass an area stretching from the Caucasus to China’s western province of Xinjiang, under the new banners of the Islamic Party of Turkestan in April 2001 and the Islamic Movement of Turkestan in May 2001.

The IMU is on the United Nations 1267 Committee’s consolidated list, proscribed also by the UK, US, Australia and Canada and many other governments.

By the end of the 1990s, the IMU had relocated to Afghanistan, due to the lack of support for the movement in Uzbekistan and the measures taken against it by the Uzbek government. The co-founder of the IMU, Tahir Yuldashev was killed in an August 2009 US drone strike in Waziristan. The new IMU leader, Usmon Odil, is a longtime associate of Yuldashev and was named Yuldashev’s successor before his death.

Yuldashev soon became popular – a star speaker at mosques – in the Sheen Warsak region near Wana, following his retreat from Afghanistan. Once well-entrenched, he founded an organization that he dubbed Mohajireen-o-Ansar, which mean refugees and friends or supporters in Arabic, to pursue his agenda, which essentially converged with that of Al Qaeda. A Pakistani Punjabi fugitive called Qari Mudassir used to act as a spokesman for the group. Yuldashev also set up a private jail to try and punish enemies and dissidents.

Yuldashev’s revered status took a hit when his vigilantes began targeting Pakistan army and government officials beginning in late 2006, turning the Uzbeks from revered heroes to villains in the eyes of their Pakistani hosts. Mullah Nazir also disapproved of targeting the Pakistani army and civilians, and hence the March 2007 operation.

But despite the limits that the new geo-military situation put on the IMU’s area of influence, it has indeed morphed into a lethal non-Arab Al Qaeda entity. From the late 1990s, when the Uzbeks opened their first training camp near Mazar-e-Sharif in northern Afghanistan, to their escape to South Waziristan from the US-led Operation Anaconda in 2002, most of the Uzbeks are clearly under tremendous strain, struggling to make their last stand in the face of unprecedented impatience within the Pakistani military establishment and the government.

I saw quite a few of them during my visit to Wana and these villages in April and June 2004. My hosts – the family of late Allah Noor, a journalist murdered in mysterious circumstances later that year, were also hosting some Uzbeks. He used to bemoan the fact that by dint of luck they got Uzbeks as guests. “They don’t have enough dollars, poor compared to Arabs,” he would say.

But as it turned out, the IMU grew in strength, enmeshing socio-culturally with locals and also increasingly radiating a radical world view that the Arab-African Al Qaeda stood for.

Apprehensive of the gradually shrinking space because of the army presence in the region, the IMU also began targeting security forces or their local allies, possibly deluded that they could get away with their brutal campaign. But the army’s patience ran out in March 2007 when it decided to take the bull by the horn; it embedded commandos in the private army of Mullah Nazir, then the mighty warlord representing Ahmedzai Wazir tribes. Within a few days, Nazir and the army evicted the Uzbeks and their local supporters, forcing them to find refuge with Baituallah Mehsud in areas such as Makeen, Ladha, Srarogha. When Baituallah founded the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) in December that year, it became a stronger socio-political cover for them, and they began partnering with TTP for attacks on security forces as well as funds-mobilization by supporting organized crime such as kidnappings for ransom and extortions.

[quote]Commandos were embedded in Mullah Nazir's private army to evict the Uzbeks and their local supporters[/quote]

Then came the year 2009, one of the deadliest in TTP-led violence. And the army decided to retake the Mehsud regions that the TTP had occupied since its creation.

“It is a do or die situation for [the Uzbeks] so they are scrambling for protection and would do anything for survival,” former Pakistan Army Chief of Staff, Gen Ashfaq Kayani, had told us during a briefing days before the October 17 military march on TTP strongholds. The Uzbeks have assumed a “wild card” status in a region where their safe space has gradually been shrinking, Kayani had said.

One of the major reasons for the 2007 and 2009 operations were the hundreds of tribal contacts and intelligence assets that the IMU in particular had executed for espionage, a task given to it by the TTP. The 2009 operation pushed the TTP and its Uzbek guests in to the mountainous terrain that separates North Waziristan from the South, many also sheltering with Hafiz Gul Bahadur.

In the month of May, the IMU became a target again, of a sustained aerial bombing campaign that left some 100 fighters dead, including Uzbeks and Chinese Uighurs who have been holding out in Sahwaal, Shaktoi, and adjacent areas. The reason: these foreign fighters had turned Waziristan into an Al Qaeda nest, and were using it for their terrorist operations against Pakistani and Chinese interests.

Their presence became unbearable also because it is no more compatible with the increasing Pakistan-China cooperation. The East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), for instance, openly vows to hurt Chinese interests wherever they are. And both the TTP as well as IMU supplement the ETIM agenda.

The origins of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan date back to the early 1990s, when Namangani joined forces with Tahir Yuldashev (variant Yuldosh), an unofficial mullah and head of the Adolat (Justice) Party, with the aim to implement Sharia law in the city of Namangan in Uzbekistan’s part of the Ferghana Valley. The government banned the Adolat Party in March 1992. A period of repression followed, forcing many Islamic militants to flee the Ferghana Valley. Namangani fled to Tajikistan, where he participated in the Tajik Civil War and established a base for his fighters in that country. Yuldashev travelled to Afghanistan, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, establishing links with other Islamic militants. He also made clandestine trips to Uzbekistan, maintaining contact with his supporters and setting up underground cells.

Their stated goal, as posted on the internet in August 1999, is the ‘establishment of an Islamic state with the application of the Sharia’ in Uzbekistan.

The IMU expanded its territorial focus to encompass an area stretching from the Caucasus to China’s western province of Xinjiang, under the new banners of the Islamic Party of Turkestan in April 2001 and the Islamic Movement of Turkestan in May 2001.

The IMU is on the United Nations 1267 Committee’s consolidated list, proscribed also by the UK, US, Australia and Canada and many other governments.

By the end of the 1990s, the IMU had relocated to Afghanistan, due to the lack of support for the movement in Uzbekistan and the measures taken against it by the Uzbek government. The co-founder of the IMU, Tahir Yuldashev was killed in an August 2009 US drone strike in Waziristan. The new IMU leader, Usmon Odil, is a longtime associate of Yuldashev and was named Yuldashev’s successor before his death.

Yuldashev soon became popular – a star speaker at mosques – in the Sheen Warsak region near Wana, following his retreat from Afghanistan. Once well-entrenched, he founded an organization that he dubbed Mohajireen-o-Ansar, which mean refugees and friends or supporters in Arabic, to pursue his agenda, which essentially converged with that of Al Qaeda. A Pakistani Punjabi fugitive called Qari Mudassir used to act as a spokesman for the group. Yuldashev also set up a private jail to try and punish enemies and dissidents.

Yuldashev’s revered status took a hit when his vigilantes began targeting Pakistan army and government officials beginning in late 2006, turning the Uzbeks from revered heroes to villains in the eyes of their Pakistani hosts. Mullah Nazir also disapproved of targeting the Pakistani army and civilians, and hence the March 2007 operation.

But despite the limits that the new geo-military situation put on the IMU’s area of influence, it has indeed morphed into a lethal non-Arab Al Qaeda entity. From the late 1990s, when the Uzbeks opened their first training camp near Mazar-e-Sharif in northern Afghanistan, to their escape to South Waziristan from the US-led Operation Anaconda in 2002, most of the Uzbeks are clearly under tremendous strain, struggling to make their last stand in the face of unprecedented impatience within the Pakistani military establishment and the government.