For Rene Char, the French poet, “To live is to persist in finishing a memory”; and for Iram Zia Raja, the artist based in Lahore, to live is to persist in mapping a memory. Not only our private recollections, but the cultural past which has manifested in multiple forms, formats, materials, images, techniques, and textures. Her current one-person exhibition “Texture of Time” (being held from 11th to 24th June 2024, at Canvas Gallery, Karachi), brings forth the artist’s position towards appropriating historic imagery, and popular pictorial practices by an inhabitant of global village living in the twenty-first century.

Even our individual, intimate and deeply buried memories, whenever recalled, assume different versions. Similar is the case for the shared visual expressions of a milieu. Transmitted n/through objects not made by one person, nor for the consumption or pleasure of a single human being. Exquisite examples of textile, jewellery, footwear, toys, pottery, religious iconography, furniture, and numerous other utilitarian pieces require a collaboration in executing them, (hence no space/concept for personalized signature!), and are used by families, friends, colleagues, generations, (thus no idea of individual ownership. For instance, an embroidered kurta could be worn by multiple women, perhaps spread to disconnected regions).

In her earlier works one senses an aspect of documentation, perseverance, and persistence when it comes to historic material; but her later works, actually the most recent ones, turn more abstract in their sensibility

Iram Zia Raja, a professor of design with a PhD in Art History, researches, investigates, and analyses diverse traditional products, which have continued till our times. Occasionally with a shift in their initial function, substance, structure, and aesthetic features. For instance, Amir Khusrau’s original qawwalis (originated in late-thirteenth to early fourteenth century) are still performed, with numerous changes in their composition, audience, and purpose. A qawwali being sung and admired today is a passage of memory, involving the artist and the community.

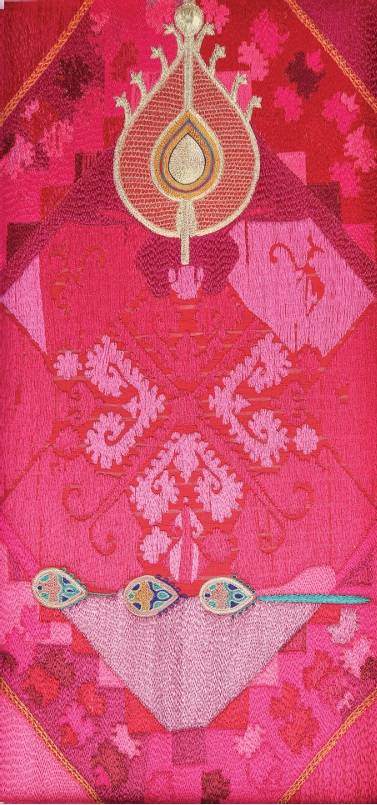

Similarly the art of Iram Zia, is an attempt in drawing, reminding, and reaffirming the pictorial legacy of a culture. Her textile-based pieces signify an artist’s distinct way of looking at the past, and transforming it into a new entity, which may transcend the separation of time.

One usually links memories, or history with the past, but if a text on prehistoric art, Greek philosophy, pre-Islamic poetry is published in, say, 2020 – it primarily belongs to the twenty-first century. Like whatever we remember is part of (our) current now.

Viewed from this perspective, the art of Iram Zia Raja, holds another significance. Bridging the gulf between art and craft, and challenging the divide between genders linked to traditional practices (embroidery, quilt making, patchwork, felting, stitching) being associated with women (hence exiled from the discourse of art).

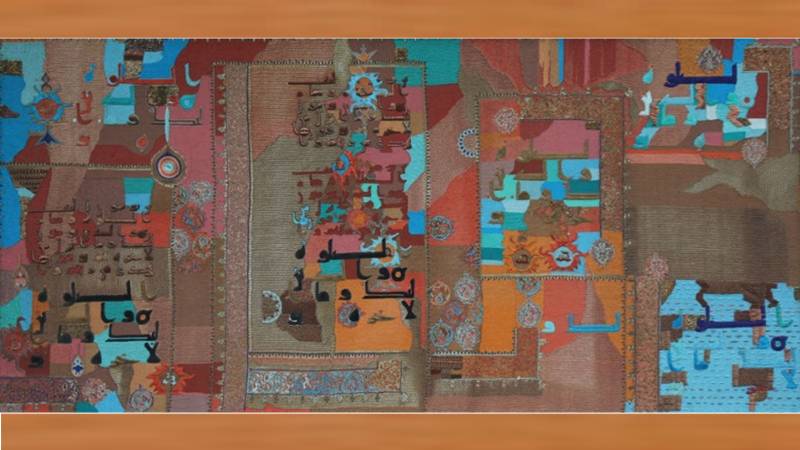

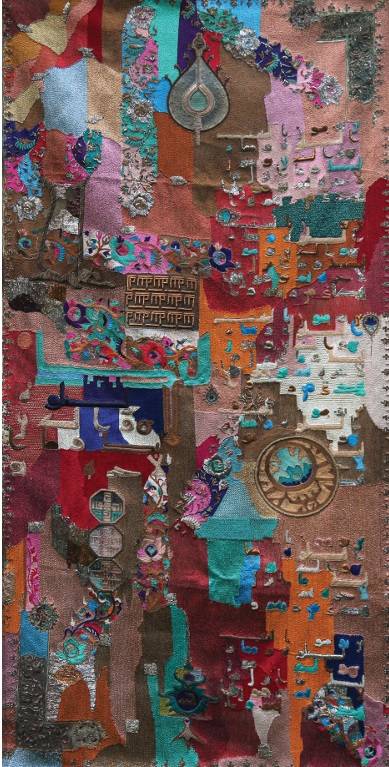

Zia’s works from her solo exhibition can be read, enjoyed and admired for their complexity: of meaning, material, method. She has incorporated motifs from the Islamic manuscripts, Muslim monuments, sections of Kufic script, decorative patterns found in traditional textile, and ornaments of South Asia to produce unique artworks.

Dating from 2011 to 2023, Raja’s 20 works on display in the gallery indicate a personal history of the artist. In her earlier works one senses an aspect of documentation, perseverance, and persistence when it comes to historic material; but her later works, actually the most recent ones, turn more abstract in their sensibility even though a few traditional elements can yet be tracked. The practice of pattern making is abstract in any case, because the image of a flower is converted into an idea of flower by making it a floral design. The new works of Iram Zia Raja with their unusual compositions, uncanny chromatic order, and the unconventional application of skill represent the art of the present; of a person who approaches memory in a creative manner, and brings out a new, exciting, and unforgettable “past” which, in the words of Mia Couto, “has not yet passed.”