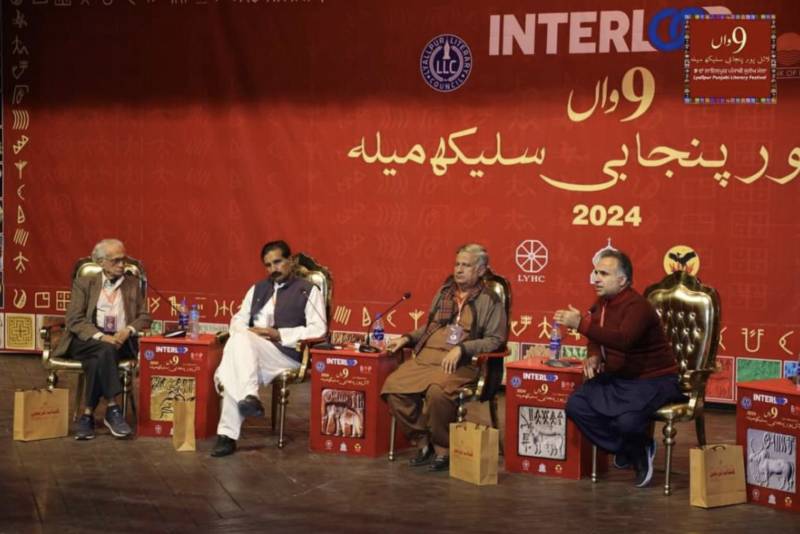

In a recent engagement at the Lyallpur Punjabi Sulekh Mela, jointly organized by the Lyallpur Young Historian Club (LYHC) and Lyallpur Literary Council (LLC), a pivotal session on the state of Punjab's dying rivers unfolded. As the moderator of this significant dialogue, I had the privilege of witnessing a diverse panel delve into the profound importance of rivers in preserving Punjab's cultural identity and fostering sustainable development.

Among the panelists, Dr. Parvez Vandal illuminated the adverse impacts of canal colonization on Punjab's multifaceted economy. Integrating agriculture, pastoral, and industrial activities, Dr. Vandal stressed how canal colonization disrupts the economic development model, restricting agricultural progress to meet colonial market demands.

Dr. Zafar Haral highlighted the cultural significance of Punjab's rivers, shedding light on how canal colonization creates a sense of alienation among the local inhabitants of riverine communities. Ignored in new land enclosure canal schemes, this neglect leads to internal feuds, altering traditional customs of protecting rivers from external pollution. Addressing historic injustices becomes imperative to revive the people's relationship with nature.

Punjabi writer Nain Sukh added another layer to the discourse, focusing on how canal colonization gives rise to new diseases due to waterlogging and salinity. Beyond polluting rivers, canal colonization schemes create social upheaval, contributing to a surge in land ownership disputes, with 80% of court cases originating from these disputes.

The highly charged resource nationalism discourse led to river division instead of water sharing, neglecting norms of global experience and environmental considerations.

While the session rightly underscored the challenges of canal colonization for river ecology, it lacked a nuanced discussion on the path toward ecological transition. The historical path dependency, spanning over 150 years from the colonial period to post-1947, needs careful examination.

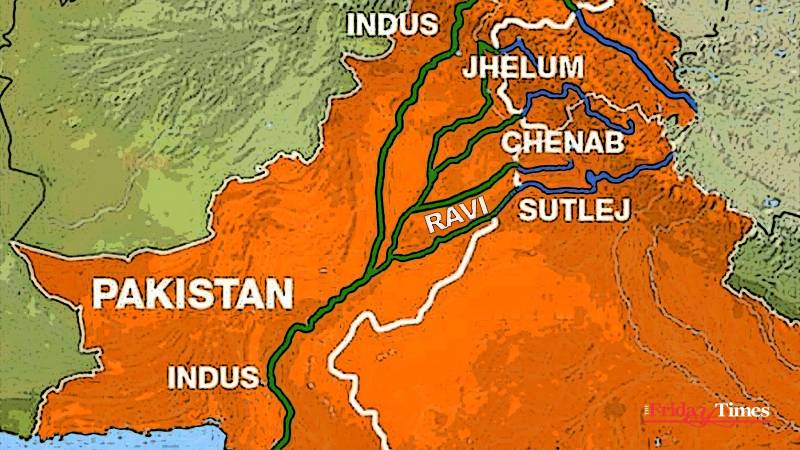

The partition of Punjab posed another challenge – sharing transboundary water resources between the newly established states, Pakistan and India. The 1960 Indus Water Treaty, hailed as a second wave of attack on Punjab's rivers, almost abandoned three eastern rivers, diverting water to water intensive crop fields and even provide water beyond the Indus basin boundaries. The highly charged resource nationalism discourse led to river division instead of water sharing, neglecting norms of global experience and environmental considerations.

In a noteworthy initiative last Sunday, local activists gathered under the banner "Ravi Bachao Tehreek" at the Ravi River's waterfront in Lahore, Pakistan, and at two distinct places on the other side of the border in East Punjab (India) at Sutlej and Beas River's waterfront. They embraced rivers' cultural values and demanded the restoration of dying rivers through appropriate amendments to the Indus Water Treaty.

According to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), until 1965, West Pakistan did not rank among the top 15 countries in global rice production. However, by the year 2022, Pakistan has risen to become the 10th largest rice-producing nation worldwide. This transformation underscores the significant shift in agricultural focus, emphasizing the contemporary dominance of rice cultivation compared to historical patterns.

Reviving Punjab's dying rivers is an "absurdly difficult but not impossible" task, given the considerable time that has passed. Fundamental understandings must guide this revival, including basin-level planning, consensus to halt new land enclosures, and cessation of water withdrawal from streams. Developing a suitable mix of crop choices, considering agroecological viability and fixing crop zoning, is crucial. Reorienting national level agricultural policies in the Indus Basin from colonial and neocolonial food and crop regimes to align with local needs and ecological considerations is imperative. In the colonial era, the British implemented an extensive canal network and land enclosures in the Indus Basin to cater to the demands of European markets. This infrastructure served the purpose of facilitating the cultivation of wheat and cotton, providing a source of cheap labor and abundant natural resources to meet the needs of the colonial power.

The path dependency of agrarian resource extractivism, continuing for 150 years, needs to be reconsidered. Fast forward to the neocolonial period, and the echoes of this historical path dependency persist, manifesting in the form of an extensive rice cultivation trend. Over the past few decades, rice cultivation has seen substantial growth, albeit at an environmental cost. This particular crop now accounts for over 50 percent of irrigation supplies in the Asian continent, illustrating its widespread adoption and impact.

An illustrative example of this shift in agricultural patterns is evident when considering Pakistan's rice production trajectory. According to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), until 1965, West Pakistan did not rank among the top 15 countries in global rice production. However, by the year 2022, Pakistan has risen to become the 10th largest rice-producing nation worldwide. This transformation underscores the significant shift in agricultural focus, emphasizing the contemporary dominance of rice cultivation compared to historical patterns.

By uniting farmers across borders in a collective struggle, the farmers' movement seeks to challenge existing paradigms and advocate for sustainable agricultural practices.

The environmental implications of this shift are noteworthy, as the increased cultivation of water-intensive crops like rice places a substantial demand on irrigation resources. This not only alters the landscape of agriculture, but also raises concerns about sustainable water usage and environmental conservation.

In essence, the historical path set during the colonial period, characterized by canal networks and land enclosures, has evolved into a modern-day agricultural landscape dominated by rice cultivation. Understanding this historical trajectory is crucial in devising sustainable solutions for the present and future, especially in the context of reviving Punjab's dying rivers and promoting ecological balance.

At the heart of the endeavor to revive Punjab's dying rivers lies the pivotal role of a critical transnational peasant movement rooted in agroecology tradition. This movement serves as the linchpin, offering a transformative force capable of reshaping the agrarian landscape of Punjab. By uniting farmers across borders in a collective struggle, the movement seeks to challenge existing paradigms and advocate for sustainable agricultural practices. Embracing the principles of agroecology, these farmers envision a future where ecological balance and cultural values are reinstated. Through their collective efforts, the critical agroecology farmers' movement strives not only to address historic injustices, but also to spearhead a new era of environmental consciousness, fostering the revival of Punjab's deteriorating rivers