In Akhtar’s 2011, we find, among other fascinating things, a direct reference to some eminent Progressive poets; the parodies of Faiz Ahmad Faiz and Noon Meem Rashid are there without mentioning their names. There is just a harmless parody of Faiz’s poem; while there is a light suspicion of satire in the parody of Rashid. For example, Faiz’s poem:

‘Muj se pehli si mohabbat meri mehboob na maang

Main ne samjha tha ke tu hai to darakhshaan hai hayaat’

(My love, do not ask me for that old love again

I had felt that with you around, the world would be luminous)

Mohammad Khalid Akhtar wrote:

‘Mujh se pehli si aqeedat mere Manato na maang

Main ne samjha tha ke tujh main himmat hogi

Magar yeh mera khayal ghalat tha’

(My love, do not ask me for that old affection again

I had felt that you will possess courage

But I was wrong in my imagination)

In short, this is a complete satirical work. One finds very lively and grand satire on various aspects of life: the Westernization of the Arabs, the willfulness of the rulers of great countries, the Marxist system, newspaper policies, the educational curriculum, philosophy, historians, police, the strategies and stupidities of ministers; all of these have come under the range of his scalpel-pen. He has also mentioned sex but his manner related to sex feels tired. He is found to be mentioning women generally in relation to sex rather than romanticism.

Then one also finds in the same novel a very beautiful portrait of human psychology. A person Mogilevich who destroys the whole world due to selfishness is mentioned in the following words: “Our most powerful feeling even more powerful than sexual desire, is the desire for power and fame; to rule over other humans and to order them here and there.”

At another place he writes: “Every single person is selfish and every single person is a sadist; everyone of us, too, has a Mogilevich present within us.”

At one place, while describing women, he writes:

“Women are so empty-minded and silly that to win them, high philosophy, literary taste or grand conversation and Josephic features do not work. Their preferring a male is dependent generally upon that man patting the mustaches or some similar absurd habit.”

Akhtar has maintained an air of suspense in this novel from start to finish, though to explain the situation of the world sixty years ago, on the power of imagination, is itself an astonishing thing. And then, to fill the colours of interest and intrigue into these events is definitely an artistic act.

He has created a very interesting situation in this novel through the actions and pauses of the strange characters of Mr Popo and Sergeant Buzzfir. Their firing by means of a machine; their slinking away silently after getting news of their dismissal; participation in the meeting of the open-air lovers; going into the bazsar of the ones with the coloured lips; then returning in disguise via plane and recapturing the government. There is a wave of suspense running through the warp and weft of all these events and the reader is kept in a state of constant anticipation as to what will happen next.

The language of this novel is of general conversation, in which there is a very fearless use of English words as well. Some sentences indeed feel wholly like a literal translation. This is the reason Muhammad Kazim thinks that to translate Mohammad Khalid Akhtar’s works into English is perhaps the easiest task in the world.

Englishness pervades every vein of this work. Perhaps this is because he thinks in English and writes in Urdu. There is a rebellion-like manner in the matter of the structure of his sentences, his language and descriptions. He has done all of this intentionally, because according to him, to acquit an obligation with the ‘strange atmosphere’ of his world needed an erroneous and astonishing language. He writes: “Urdu has for too long been treated as a pure virgin. I do not regard Urdu as so sensitive as to be unable to bear a bit of informality and ill-manneredness.”

So as justification for using such type of language, he gives examples of Quratulain Hyder, Sir Syed and Shibli Nomani, etc. who go very far in their efforts for the expansion and evolution of the Urdu language.

In my opinion, any language accepts only those rules of expansion and evolution which are natural, otherwise words used merely for fashion or innovation become a cause of strangeness and alienation for any writing. Had Mohammad Khalid Akhtar, too, kept the natural demands of language in mind rather than following a few exceptional examples, this first-ever fantasy in Urdu literature would have been a masterpiece in every way.

And as far as the question of its ‘strange atmosphere’ and astonishing readers is concerned, one can argue that these qualities should be there in the plot, events, characters and milieu of any work, not in the language of it.

This is a novel of fast tempo and consistent plot, in which events move forward with great speed. In it, all the force has been spent on the actions and pauses of the characters. In most of Akhtar’s works, the whole story generally revolves around characters. Eminent humourist Ibne Insha had written on the flap of Akhtar’s novel Chakiwara Main Visaal (Love in Chakiwara) that the renowned characters of Akhtar, Chacha Abdul Baqi and nephew Bakhtiar Khilji prior to this – meaning in Chakiwara Main Visal – are seen in the form of Qurban Ali Kattar and Mr Changezi. But in my opinion, both these characters even before that appear in Akhtar’s fantasy 2011 as Mr Popo and Sgt. Buzzfir. The same simple-naturedness, the same naivete, the same idiotic actions; their new projects and schemes and failures. In addition to these two main characters, the characters of F.L. Patakha, Hoot, Chhota Kabo, Bada Kabo, Vazir-e-Jhoot (Minister of Lies) and Vazir-e-Jahalat (Minister of Ignorance) are important.

Khalid Akhtar never lets purposiveness in his writings disappear from sight. Perhaps the reason for this is his guru Robert Louis Stevenson’s view: “And a well-written novel calls out and repeats its purpose and responsibility from every chapter, every page and sentence.”

Akhtar’s ideas about the Muslim nation in this novel are very enlightened and he is very optimistic about international Muslim unity. He has named the Muslim world as ‘Islamistan’.

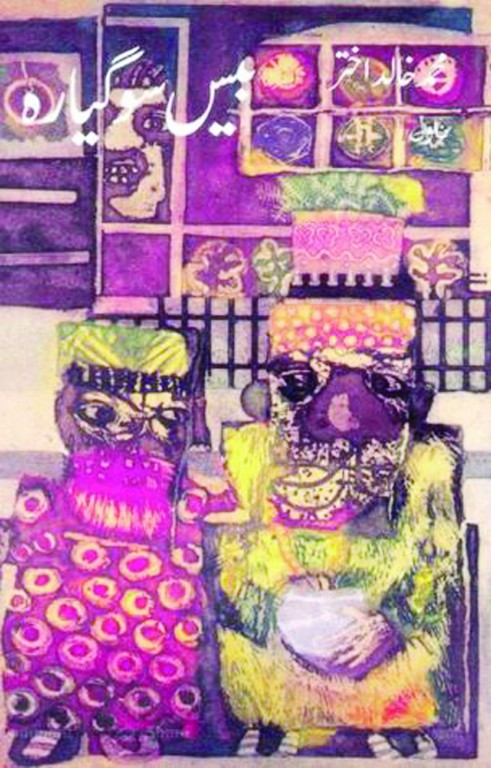

In short, 2011 for all its wonders and defects and strangeness of language is a singular and unique work of Urdu literature, which Akhtar himself was very fond of. He writes at a place, “2011, which I wrote in a narrow and dark flat of Karachi, is the most prized of my books.”

Then in one of his essays, while discussing this fantasy in detail, he writes:

“In 1950, I wrote a fantasy 2011, influenced by Orwell’s 1984. I wrote 2011 with a poison-dipped pen in rage. It is said to be a fantasy but actually a satire on the national circumstances, political scene and society of that time. Despite the defects of language and narrative, I had this feeling that my book is good. Upon my prompting, the publisher sent a copy to Kanhaiya Lal Kapoor in Jalandhar. Kapoor realized what I had written under the cover of fantasy. He wrote to my publisher in a letter that ‘2011’ is the first political and social satire in the Urdu language and would that he be its author. That is, I got a reward for my labour. I no longer felt bad that most of the readers do not get what I want to say.”

That’s Akhtarian. And it’s no longer a prophecy. And 70 years later in Naya Pakistan, that no longer feels like much of an “if.”

All translations from the Urdu are by the writer.

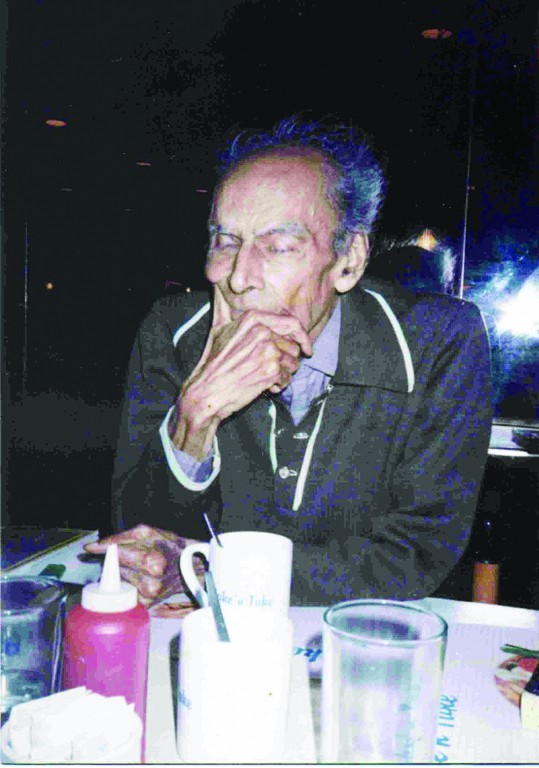

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, activist, book critic, award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where is the President of the Progressive Writers Association (Anjuman Taraqqi Pasand Musannifeen). He is currently translating Muhammad Khalid Akhtar’s ‘Bees Sau Gayara’ into English and may be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com

‘Muj se pehli si mohabbat meri mehboob na maang

Main ne samjha tha ke tu hai to darakhshaan hai hayaat’

(My love, do not ask me for that old love again

I had felt that with you around, the world would be luminous)

Mohammad Khalid Akhtar wrote:

‘Mujh se pehli si aqeedat mere Manato na maang

Main ne samjha tha ke tujh main himmat hogi

Magar yeh mera khayal ghalat tha’

(My love, do not ask me for that old affection again

I had felt that you will possess courage

But I was wrong in my imagination)

In short, this is a complete satirical work. One finds very lively and grand satire on various aspects of life: the Westernization of the Arabs, the willfulness of the rulers of great countries, the Marxist system, newspaper policies, the educational curriculum, philosophy, historians, police, the strategies and stupidities of ministers; all of these have come under the range of his scalpel-pen. He has also mentioned sex but his manner related to sex feels tired. He is found to be mentioning women generally in relation to sex rather than romanticism.

Then one also finds in the same novel a very beautiful portrait of human psychology. A person Mogilevich who destroys the whole world due to selfishness is mentioned in the following words: “Our most powerful feeling even more powerful than sexual desire, is the desire for power and fame; to rule over other humans and to order them here and there.”

At another place he writes: “Every single person is selfish and every single person is a sadist; everyone of us, too, has a Mogilevich present within us.”

At one place, while describing women, he writes:

“Women are so empty-minded and silly that to win them, high philosophy, literary taste or grand conversation and Josephic features do not work. Their preferring a male is dependent generally upon that man patting the mustaches or some similar absurd habit.”

Englishness pervades every vein of this work. Perhaps this is because he thinks in English and writes in Urdu. There is a rebellion-like manner in the matter of the structure of his sentences, his language and descriptions. He has done all of this intentionally

Akhtar has maintained an air of suspense in this novel from start to finish, though to explain the situation of the world sixty years ago, on the power of imagination, is itself an astonishing thing. And then, to fill the colours of interest and intrigue into these events is definitely an artistic act.

He has created a very interesting situation in this novel through the actions and pauses of the strange characters of Mr Popo and Sergeant Buzzfir. Their firing by means of a machine; their slinking away silently after getting news of their dismissal; participation in the meeting of the open-air lovers; going into the bazsar of the ones with the coloured lips; then returning in disguise via plane and recapturing the government. There is a wave of suspense running through the warp and weft of all these events and the reader is kept in a state of constant anticipation as to what will happen next.

The language of this novel is of general conversation, in which there is a very fearless use of English words as well. Some sentences indeed feel wholly like a literal translation. This is the reason Muhammad Kazim thinks that to translate Mohammad Khalid Akhtar’s works into English is perhaps the easiest task in the world.

Englishness pervades every vein of this work. Perhaps this is because he thinks in English and writes in Urdu. There is a rebellion-like manner in the matter of the structure of his sentences, his language and descriptions. He has done all of this intentionally, because according to him, to acquit an obligation with the ‘strange atmosphere’ of his world needed an erroneous and astonishing language. He writes: “Urdu has for too long been treated as a pure virgin. I do not regard Urdu as so sensitive as to be unable to bear a bit of informality and ill-manneredness.”

So as justification for using such type of language, he gives examples of Quratulain Hyder, Sir Syed and Shibli Nomani, etc. who go very far in their efforts for the expansion and evolution of the Urdu language.

In my opinion, any language accepts only those rules of expansion and evolution which are natural, otherwise words used merely for fashion or innovation become a cause of strangeness and alienation for any writing. Had Mohammad Khalid Akhtar, too, kept the natural demands of language in mind rather than following a few exceptional examples, this first-ever fantasy in Urdu literature would have been a masterpiece in every way.

And as far as the question of its ‘strange atmosphere’ and astonishing readers is concerned, one can argue that these qualities should be there in the plot, events, characters and milieu of any work, not in the language of it.

At another place he writes: “Every single person is selfish and every single person is a sadist; everyone of us, too, has a Mogilevich present within us”

This is a novel of fast tempo and consistent plot, in which events move forward with great speed. In it, all the force has been spent on the actions and pauses of the characters. In most of Akhtar’s works, the whole story generally revolves around characters. Eminent humourist Ibne Insha had written on the flap of Akhtar’s novel Chakiwara Main Visaal (Love in Chakiwara) that the renowned characters of Akhtar, Chacha Abdul Baqi and nephew Bakhtiar Khilji prior to this – meaning in Chakiwara Main Visal – are seen in the form of Qurban Ali Kattar and Mr Changezi. But in my opinion, both these characters even before that appear in Akhtar’s fantasy 2011 as Mr Popo and Sgt. Buzzfir. The same simple-naturedness, the same naivete, the same idiotic actions; their new projects and schemes and failures. In addition to these two main characters, the characters of F.L. Patakha, Hoot, Chhota Kabo, Bada Kabo, Vazir-e-Jhoot (Minister of Lies) and Vazir-e-Jahalat (Minister of Ignorance) are important.

Khalid Akhtar never lets purposiveness in his writings disappear from sight. Perhaps the reason for this is his guru Robert Louis Stevenson’s view: “And a well-written novel calls out and repeats its purpose and responsibility from every chapter, every page and sentence.”

Akhtar’s ideas about the Muslim nation in this novel are very enlightened and he is very optimistic about international Muslim unity. He has named the Muslim world as ‘Islamistan’.

In short, 2011 for all its wonders and defects and strangeness of language is a singular and unique work of Urdu literature, which Akhtar himself was very fond of. He writes at a place, “2011, which I wrote in a narrow and dark flat of Karachi, is the most prized of my books.”

Then in one of his essays, while discussing this fantasy in detail, he writes:

“In 1950, I wrote a fantasy 2011, influenced by Orwell’s 1984. I wrote 2011 with a poison-dipped pen in rage. It is said to be a fantasy but actually a satire on the national circumstances, political scene and society of that time. Despite the defects of language and narrative, I had this feeling that my book is good. Upon my prompting, the publisher sent a copy to Kanhaiya Lal Kapoor in Jalandhar. Kapoor realized what I had written under the cover of fantasy. He wrote to my publisher in a letter that ‘2011’ is the first political and social satire in the Urdu language and would that he be its author. That is, I got a reward for my labour. I no longer felt bad that most of the readers do not get what I want to say.”

That’s Akhtarian. And it’s no longer a prophecy. And 70 years later in Naya Pakistan, that no longer feels like much of an “if.”

All translations from the Urdu are by the writer.

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, activist, book critic, award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where is the President of the Progressive Writers Association (Anjuman Taraqqi Pasand Musannifeen). He is currently translating Muhammad Khalid Akhtar’s ‘Bees Sau Gayara’ into English and may be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com