All of us over 40 years of age have friends or relatives we think of as Luddites—those who cannot seem to handle the omnipresent rapidly advancing communication technology, smart phones that seem to get smarter every year, tablets, laptop and desktop computers, and proliferating paraphernalia, as well as the proliferating modes of communication, that seems to go with this technological revolution. These modern Luddites are recognizable by their aversion to using these devices and channels, and by their enraged looks and expletives deleted when they try to use them. Their rage is clearly against the new technology itself, and is often generalized into rage against technological progress. These days the term Luddite is commonly used to describe someone who is, on general principles, opposed to technological change. Yet technological change is a constant in our life and our economies, and is presently perhaps the most serious of our short- and long-term problems, and not just economic ones.

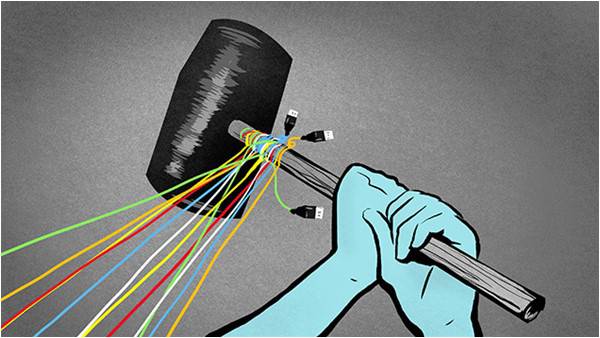

It is a common misperception that the Luddites of history, who became a problem for British textile manufacturers and governments of the day during the Napoleonic era (1811-1816), raged against technological progress, and smashed technologically improved weaving machines in order to force a return to a simpler age. However, the real truth is that Luddites were not smashing these machines because of some retrogressive ideological worship of a golden age, but because these new machines took less skill to operate and thus allowed the manufacturers to employ lesser-skilled, lower-wage workers in their place. In other words, the Luddites losing their jobs to lesser-skilled workers, were early precursors of the technological trap that has haunted us, at an accelerated pace, since the industrial revolution began in earnest around 1760. The Luddites were not the first workers displaced by technological progress—there were others before them—but they were the first to be organized in a resistance and the first to use sledgehammers to solve their problem. They were put down by force around 1816.

I am reminded of this economic history by an article I just came across by Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo of MIT, entitled, “The Race Between Machine and Man…” which was published in May of 2016 as a Working Paper of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Anything by Acemoglu commands my attention as he coauthored the best book I have ever read on the economic and political development of nations, “Why Nation Fail.” This paper takes up the increasingly urgent question of whether digital technologies, robotics, and artificial intelligence will replace skilled workers with lesser-skilled ones, and will cause wages to decline. As Acemoglu writes, “similar claims have been made, but have not always come true, about previous new technologies.” John Maynard Keynes, for example, predicted in 1930 that new technologies which he foresaw coming into use in the 20th Century would create widespread technological unemployment, even while increasing per capita incomes. There have been other well-known economists who came to the same pessimistic conclusions, none of which proved true—in the long term.

The article by Acemoglu and Restrepo puts together in an analytical framework the two effects that make up what I call the technological trap. The first effect is when a very new and efficient technology replaces human labour and leads over time to reduced employment, and/or to wage reductions (as in the Luddite case) or stagnant wages which characterize the economies of most of the industrial world at present. The second effect is that in the long run, the increased productivity that the new efficient technology has produced spurs growth and demand, which in turn leads to the creation of, in Acemoglu’s words, “more complex versions of existing tasks in which labour has a comparative advantage.” I have added “in the long run,” as that would seem key to the policy implications of these findings. Yes, the Second Industrial Revolution, which followed the Luddite period by about 40 years, demonstrates this second effect: not only did railroads replace stagecoaches and steamboats replace sail boats, and so on, but many new labour-intensive tasks were created. There was then a need for engineers, machinists, repairmen, conductors, and so forth. But I suspect the Luddites were all dead by then and their children trapped as an immiserized proletariat.

In other words, there are two contradictory forces at work in the process of technological change in the labour market of industrialized economies, and in the end a reduction in the labour share of GDP is not necessarily permanent. The first force is automation, in some form or other, of tasks heretofore performed by labour. This means that fewer, and usually lower-skilled, workers are required to do the task. The second force, or counter force, is that automation itself creates new tasks that require labour with new and different skills. A good example is the retooled auto plants still operating in the US; the old assembly line of Henry Ford, with lines of narrowly skilled workers doing one small task are long gone and the on new assembly lines these tasks are done by machines for the most part, with far fewer high-skilled workers operating the machines. This kind of process is going on at great speed, not just in the industries that are left, but throughout the US economy. In banking, for example, ATMs reduce the bevy of clerks in retail banks to a handful, but require those clerks left to be much more highly trained. For workers with the new, up-to-date skills, competition is fierce and wages are buoyant.

But where do the auto or bank workers, replaced by machines, go for work. Some might go for retraining in the hope that new auto plants or banks spring up which can use their newly acquired skills. But in the US most wind up in the lower skill, lower wage retail service sector, in which wages have stagnated for much of the last two decades. They have to take lower paying jobs in sectors in which the hope of wage buoyancy is minimal. Yet many employers in the more automated industrial plants complain that the lack of workers with the proper skills to run the complex machinery is retarding their investment/expansion plans. Something is missing in this picture.

Clearly the second force that automation is supposed to set off, that is the creation of new complex tasks, is slow in developing. Do we dare just muddle through, letting the labour market continue to bifurcate on its own into two markets, one for a minority of workers who have somehow acquired the skills to join the buoyant wage sector, and a second one, a majority of the workforce who will be stuck in jobs that are low skill, low wage, and low hope.

One idea that has come up for investigation is that governments provide a universal basic income to their citizens. A new book by two French economists promotes this idea, but the argument is undermined by the authors themselves, who admit that even the well-off industrial countries could not afford to provide an income that people could live on. Only Finland decided to try it on an experimental basis, but realizing its potential for bankrupting the country, limited it to 2,000 people.

The answer, really, is more government intervention in both the retraining of its citizens who have been automated to lower paying jobs or to no job at all, and also in trying to figure out how to speed up the coming of the second effect, i.e. the creation of those new complex tasks that Acemoglu and Restrepo tell us are likely to come from automation. But in the meantime, a government that could get its act together enough to promulgate a bill to fund the overhaul of America’s crumbling infrastructure would be a darn good placeholder.

The author is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC, and a former US diplomat who was Ambassador to Pakistan and Bangladesh

It is a common misperception that the Luddites of history, who became a problem for British textile manufacturers and governments of the day during the Napoleonic era (1811-1816), raged against technological progress, and smashed technologically improved weaving machines in order to force a return to a simpler age. However, the real truth is that Luddites were not smashing these machines because of some retrogressive ideological worship of a golden age, but because these new machines took less skill to operate and thus allowed the manufacturers to employ lesser-skilled, lower-wage workers in their place. In other words, the Luddites losing their jobs to lesser-skilled workers, were early precursors of the technological trap that has haunted us, at an accelerated pace, since the industrial revolution began in earnest around 1760. The Luddites were not the first workers displaced by technological progress—there were others before them—but they were the first to be organized in a resistance and the first to use sledgehammers to solve their problem. They were put down by force around 1816.

Automation means that fewer, and usually lower-skilled, workers are required to do the task. But automation itself creates new tasks that require labour with new and different skills

I am reminded of this economic history by an article I just came across by Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo of MIT, entitled, “The Race Between Machine and Man…” which was published in May of 2016 as a Working Paper of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Anything by Acemoglu commands my attention as he coauthored the best book I have ever read on the economic and political development of nations, “Why Nation Fail.” This paper takes up the increasingly urgent question of whether digital technologies, robotics, and artificial intelligence will replace skilled workers with lesser-skilled ones, and will cause wages to decline. As Acemoglu writes, “similar claims have been made, but have not always come true, about previous new technologies.” John Maynard Keynes, for example, predicted in 1930 that new technologies which he foresaw coming into use in the 20th Century would create widespread technological unemployment, even while increasing per capita incomes. There have been other well-known economists who came to the same pessimistic conclusions, none of which proved true—in the long term.

The article by Acemoglu and Restrepo puts together in an analytical framework the two effects that make up what I call the technological trap. The first effect is when a very new and efficient technology replaces human labour and leads over time to reduced employment, and/or to wage reductions (as in the Luddite case) or stagnant wages which characterize the economies of most of the industrial world at present. The second effect is that in the long run, the increased productivity that the new efficient technology has produced spurs growth and demand, which in turn leads to the creation of, in Acemoglu’s words, “more complex versions of existing tasks in which labour has a comparative advantage.” I have added “in the long run,” as that would seem key to the policy implications of these findings. Yes, the Second Industrial Revolution, which followed the Luddite period by about 40 years, demonstrates this second effect: not only did railroads replace stagecoaches and steamboats replace sail boats, and so on, but many new labour-intensive tasks were created. There was then a need for engineers, machinists, repairmen, conductors, and so forth. But I suspect the Luddites were all dead by then and their children trapped as an immiserized proletariat.

In other words, there are two contradictory forces at work in the process of technological change in the labour market of industrialized economies, and in the end a reduction in the labour share of GDP is not necessarily permanent. The first force is automation, in some form or other, of tasks heretofore performed by labour. This means that fewer, and usually lower-skilled, workers are required to do the task. The second force, or counter force, is that automation itself creates new tasks that require labour with new and different skills. A good example is the retooled auto plants still operating in the US; the old assembly line of Henry Ford, with lines of narrowly skilled workers doing one small task are long gone and the on new assembly lines these tasks are done by machines for the most part, with far fewer high-skilled workers operating the machines. This kind of process is going on at great speed, not just in the industries that are left, but throughout the US economy. In banking, for example, ATMs reduce the bevy of clerks in retail banks to a handful, but require those clerks left to be much more highly trained. For workers with the new, up-to-date skills, competition is fierce and wages are buoyant.

The answer, really, is more government intervention in both the retraining of its citizens who have been automated to lower paying jobs or to no job at all

But where do the auto or bank workers, replaced by machines, go for work. Some might go for retraining in the hope that new auto plants or banks spring up which can use their newly acquired skills. But in the US most wind up in the lower skill, lower wage retail service sector, in which wages have stagnated for much of the last two decades. They have to take lower paying jobs in sectors in which the hope of wage buoyancy is minimal. Yet many employers in the more automated industrial plants complain that the lack of workers with the proper skills to run the complex machinery is retarding their investment/expansion plans. Something is missing in this picture.

Clearly the second force that automation is supposed to set off, that is the creation of new complex tasks, is slow in developing. Do we dare just muddle through, letting the labour market continue to bifurcate on its own into two markets, one for a minority of workers who have somehow acquired the skills to join the buoyant wage sector, and a second one, a majority of the workforce who will be stuck in jobs that are low skill, low wage, and low hope.

One idea that has come up for investigation is that governments provide a universal basic income to their citizens. A new book by two French economists promotes this idea, but the argument is undermined by the authors themselves, who admit that even the well-off industrial countries could not afford to provide an income that people could live on. Only Finland decided to try it on an experimental basis, but realizing its potential for bankrupting the country, limited it to 2,000 people.

The answer, really, is more government intervention in both the retraining of its citizens who have been automated to lower paying jobs or to no job at all, and also in trying to figure out how to speed up the coming of the second effect, i.e. the creation of those new complex tasks that Acemoglu and Restrepo tell us are likely to come from automation. But in the meantime, a government that could get its act together enough to promulgate a bill to fund the overhaul of America’s crumbling infrastructure would be a darn good placeholder.

The author is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC, and a former US diplomat who was Ambassador to Pakistan and Bangladesh