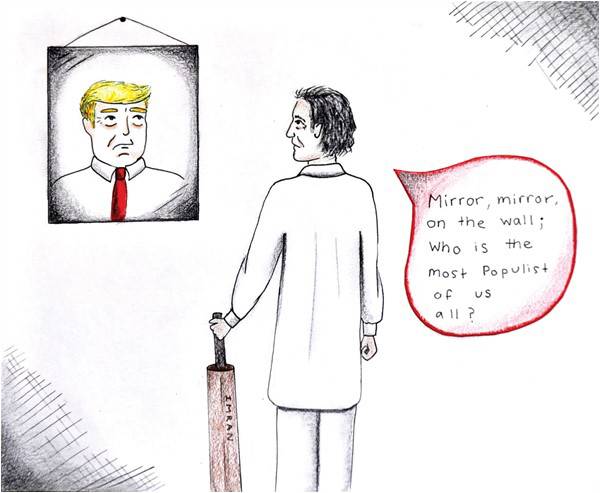

Populism is a “thin” ideology political scientists would tell us. It has only one fixed tenet: the centrality of “the people.” But populist politicians don’t mean all people, just those morally good people that share certain values and mindset, most often the same values and mindset that the populist politician professes, though not always—there are demagogues among them. Populist politicians almost always contrast “the people” with “the elite,” who they claim are corrupt and ignore the will of the people. As these politicians can’t really be taken seriously with this one thin ideology, they add other ideologies that fit their personality and their mindset. There are left-wing populists, who espouse socialism or other radical ideologies of the left, but most populists are right-wing. Ideologies such as nationalism or fascism predominate in the populist world. Imran Khan joins a rapidly expanding group of populist leaders, most of whom face serious problems that their basic populism doesn’t really address. Often, facing such problems they have to learn new ideologies on the job. I wonder sometimes, given their grab bag of ideologies, if these leaders don’t need to keep checking their mirrors to be sure of their identity. Given the frightful problems facing him, I suspect Khan checks his mirror frequently.

Last week, while still in California, an old friend who keeps up with world events, mentioned over lunch rather casually that Imran Khan was, like Donald Trump, a populist. That seems the general perception here, and derives I am sure (as with my friend) from the fact that he, like Trump, had campaigned on a platform which focused on corruption. This is, of course, a general fact among populist politicians; they all promise to root out the corruption that more traditional political leaders are thought to tolerate and even share. But aside from their focus on corruption, what can we expect from populist leaders. I suppose the answer to that is it depends on what other ideologies they have adopted, how well they have learned them, and how much they believe in them.

So perhaps we can start with the assumption that Imran Khan’s instincts will be to look through the populist prism as he stares at these complicated short-term and profound long-term problems and receives advice on how to handle them from his ministers and from the Economic Advisory Council he has just appointed. This assumption is not just based on the fact he campaigned mainly against corruption; it is buttressed by at least one action he has taken, and a number of statements he has made since his election. For example, he said “[W]e are standing with Article 295-C and will defend it” when a Dutch right-wing politician threatened to insult the Prophet (Peace Be Upon Him), and I think he even considered leading a multilateral reaction against the Netherlands which became moot when the Dutch politician backed off his threat. This was calculated to enhance his populist credentials with his supporters in a way I will cover below. A second example is his dismissal from the Economic Advisory Council of a well-known and highly-respected economist when it came to be known that this person was a member of a sect considered heretical by the religious right in Pakistan. As this dismissal led to the resignations of two other respected economists, it could mean a serious wound to that Council.

I am indebted in this paragraph to Dr. Ali Usman Qasmi who, drawing from work done by other scholars as well as his own analysis in these pages last week, has led me to understand why the statement and action described in the previous paragraph would reflect Khan’s populist instincts as well as his religious conservatism. Mr. Qasmi describes the rise of a new and generally younger segment of the population into the middle class of Pakistan, and in fact, this new middle class has become a separate but politically influential part of voting public. It comes mainly from the salaried workers of the growing service sector, instead of the doctors, lawyers and salaried government and industry sector workers that made up a smaller middle class in previous decades and sees modernisation differently than the more traditional old middle class. According to Mr. Qasmi, unlike the traditional middle class, the new middle-class views modernization through the lens of religion and especially the now-widely held principle of the affirmation of faith. Another characteristic or this new middle class is its aspiration to consume; it has driven the consumption boom of the past few years. But this aspiration has a dark side because of the income disparities in the new middle class, and this creates frustration among many and fuels its anti-status quo feelings as well as a hatred of corruption. It is this new middle class that is the core or Khan’s support, drawn by his anti-corruption, anti-elite populist message, and gave him the votes to become Prime Minister. And this is why I interpret his statement about Article 295c and his dismissal of the economist as acts inspired by his populist beliefs, which would be clearly supported by his core supporters. In this sense he is like Trump, who also pushes forward on policies which please his core supporters despite being rejected by the majority of Americans.

As I see it, Imran Khan is a leader between a rock and a hard place, and with no exit. He is a political leader with populist instincts and a core of support from a newly emerged middle class, probably, in figurative terms, feeling its oats after being told it elected him, which digs his populist philosophy as consistent with its general philosophy of religiosity and consumerism. He is also a political leader who is prime minister because the army put him there and has already shown it has his back—as long as he behaves and doesn’t tread on its toes. Moreover, he has a superior partner in the army which has long been the most conspicuous consumer in the country, consuming up to 3.5 percent of its national product and 10-15 percent of its national budget. And he now is the political leader of a nation which has been consuming more than it produces for several decades and has required several bailouts which, although designed to rectify the long-term structural deficiencies in revenue collection and economic efficiency, have failed to do so, and now faces what may well be a catastrophic balance of payments crisis.

Who takes the hit if, as I suspect will happen, Pakistan ends up going to the IMF to help it out of the balance of payments crunch? Populist leaders generally don’t want to deal with the IMF on such occasions as it is usually their constituents that bear the brunt. That would appear to be the case if Pakistan ends up with a Fund program. With a sizeable depreciation/devaluation of the rupee raising import prices considerably and spurring inflation, severe fiscal stringency probably slowing the economy more that increased exports would stimulate it, incomes would fall, and the segments of the middle class, including the new middle class of Khan supporters would suffer. It seems unlikely that army would reduce its usual share of the pie by much. Some populist leaders might threaten the ultimate bombshell—default. But I doubt he could get away with that as either the coalition would dissolve over it or the Army would veto it

The alternatives are not good. I think Khan is sort of wedged in. His plight reminds me of the first movie I ever saw, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, taken from Grimms Fairy Tales, in which the forlorn queen kept checking her mirror to ask if she was still the fairest in the land. That is why I asked my talented niece, Naomi Stults, to do the drawing that comes with this article.

The author is a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC, and a former US diplomat who was ambassador to Pakistan and Bangladesh

Last week, while still in California, an old friend who keeps up with world events, mentioned over lunch rather casually that Imran Khan was, like Donald Trump, a populist. That seems the general perception here, and derives I am sure (as with my friend) from the fact that he, like Trump, had campaigned on a platform which focused on corruption. This is, of course, a general fact among populist politicians; they all promise to root out the corruption that more traditional political leaders are thought to tolerate and even share. But aside from their focus on corruption, what can we expect from populist leaders. I suppose the answer to that is it depends on what other ideologies they have adopted, how well they have learned them, and how much they believe in them.

Imran Khan is a leader between a rock and a hard place, and with no exit

So perhaps we can start with the assumption that Imran Khan’s instincts will be to look through the populist prism as he stares at these complicated short-term and profound long-term problems and receives advice on how to handle them from his ministers and from the Economic Advisory Council he has just appointed. This assumption is not just based on the fact he campaigned mainly against corruption; it is buttressed by at least one action he has taken, and a number of statements he has made since his election. For example, he said “[W]e are standing with Article 295-C and will defend it” when a Dutch right-wing politician threatened to insult the Prophet (Peace Be Upon Him), and I think he even considered leading a multilateral reaction against the Netherlands which became moot when the Dutch politician backed off his threat. This was calculated to enhance his populist credentials with his supporters in a way I will cover below. A second example is his dismissal from the Economic Advisory Council of a well-known and highly-respected economist when it came to be known that this person was a member of a sect considered heretical by the religious right in Pakistan. As this dismissal led to the resignations of two other respected economists, it could mean a serious wound to that Council.

I am indebted in this paragraph to Dr. Ali Usman Qasmi who, drawing from work done by other scholars as well as his own analysis in these pages last week, has led me to understand why the statement and action described in the previous paragraph would reflect Khan’s populist instincts as well as his religious conservatism. Mr. Qasmi describes the rise of a new and generally younger segment of the population into the middle class of Pakistan, and in fact, this new middle class has become a separate but politically influential part of voting public. It comes mainly from the salaried workers of the growing service sector, instead of the doctors, lawyers and salaried government and industry sector workers that made up a smaller middle class in previous decades and sees modernisation differently than the more traditional old middle class. According to Mr. Qasmi, unlike the traditional middle class, the new middle-class views modernization through the lens of religion and especially the now-widely held principle of the affirmation of faith. Another characteristic or this new middle class is its aspiration to consume; it has driven the consumption boom of the past few years. But this aspiration has a dark side because of the income disparities in the new middle class, and this creates frustration among many and fuels its anti-status quo feelings as well as a hatred of corruption. It is this new middle class that is the core or Khan’s support, drawn by his anti-corruption, anti-elite populist message, and gave him the votes to become Prime Minister. And this is why I interpret his statement about Article 295c and his dismissal of the economist as acts inspired by his populist beliefs, which would be clearly supported by his core supporters. In this sense he is like Trump, who also pushes forward on policies which please his core supporters despite being rejected by the majority of Americans.

As I see it, Imran Khan is a leader between a rock and a hard place, and with no exit. He is a political leader with populist instincts and a core of support from a newly emerged middle class, probably, in figurative terms, feeling its oats after being told it elected him, which digs his populist philosophy as consistent with its general philosophy of religiosity and consumerism. He is also a political leader who is prime minister because the army put him there and has already shown it has his back—as long as he behaves and doesn’t tread on its toes. Moreover, he has a superior partner in the army which has long been the most conspicuous consumer in the country, consuming up to 3.5 percent of its national product and 10-15 percent of its national budget. And he now is the political leader of a nation which has been consuming more than it produces for several decades and has required several bailouts which, although designed to rectify the long-term structural deficiencies in revenue collection and economic efficiency, have failed to do so, and now faces what may well be a catastrophic balance of payments crisis.

Who takes the hit if, as I suspect will happen, Pakistan ends up going to the IMF to help it out of the balance of payments crunch? Populist leaders generally don’t want to deal with the IMF on such occasions as it is usually their constituents that bear the brunt. That would appear to be the case if Pakistan ends up with a Fund program. With a sizeable depreciation/devaluation of the rupee raising import prices considerably and spurring inflation, severe fiscal stringency probably slowing the economy more that increased exports would stimulate it, incomes would fall, and the segments of the middle class, including the new middle class of Khan supporters would suffer. It seems unlikely that army would reduce its usual share of the pie by much. Some populist leaders might threaten the ultimate bombshell—default. But I doubt he could get away with that as either the coalition would dissolve over it or the Army would veto it

The alternatives are not good. I think Khan is sort of wedged in. His plight reminds me of the first movie I ever saw, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, taken from Grimms Fairy Tales, in which the forlorn queen kept checking her mirror to ask if she was still the fairest in the land. That is why I asked my talented niece, Naomi Stults, to do the drawing that comes with this article.

The author is a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC, and a former US diplomat who was ambassador to Pakistan and Bangladesh