Turning to Pak-Saudi relations let us be clear. The Saudis have always seen Pakistan as one of the pillars of their defense and have been prepared to help bolster Pakistan’s capabilities and stability. There is little doubt that they have chosen favourites among Pakistani politicians. But we should also be clear that the evils we attribute to Saudi influence in Pakistan were the doing of our leaders. It was Ziaul Haq who first sought Saudi financial assistance of $200 million for his Zakat fund in 1979. It was in our national interest to seek a reversal of the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan but it was leaders of that era who insisted on fighting that war under the slogan of “Islam in Danger” rather than “Afghan nationalism”. It was our leaders who encouraged, with Saudi and Egyptian assistance, bringing into Afghanistan via Pakistan extremists from all parts of the Muslim world.

It was our clerics on both sides of the communal divide who unhesitatingly accepted the free flow of funds from Saudi Arabia and Iraq on the one hand and from Iran on the other. They created a communal divide of which we had been mercifully free and they made us the secondary battlefield of the Iran-Iraq war.

I have not researched this to the extent I would have liked, but I think that if we look back we will find that the urge to spread the Wahabi creed beyond the boundaries of Saudi Arabia reared its head only after the Iran-Iraq war when a monarchy threatened by internal dissension became even more beholden to the Saudi clergy schooled in Wahabism. That we felt the full blast of the Saudi effort is undeniable—but let us not forget the culpability of our own leaders.

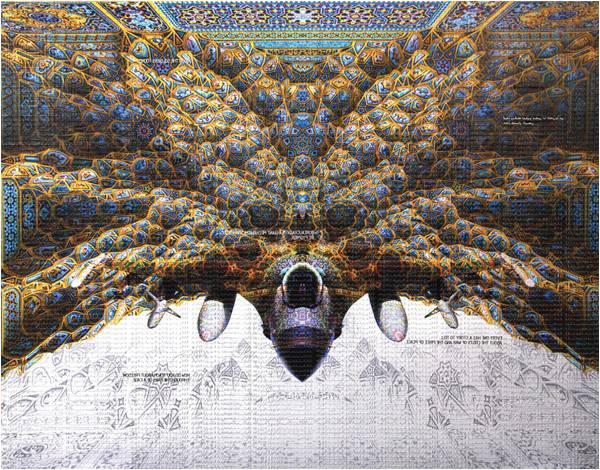

Saudi largesse was in short supply during the periods of Pakistan Peoples Party rule but it flowed plentifully in other eras be they of Nawaz Sharif or military rule. The Saudis contributed (quietly as has been their wont) $500 million for our initial purchase of F-16s in 1981-82. The Saudis matched every CIA dollar for the Afghan war and spent perhaps more than $5 billion. Apart from this, the Saudi ambassador received vast sums of money from private Saudi Zakat donors for Afghan jihad and distributed it, through our agencies, in consultation with Pakistani officials. These funds remained available for some time after the Soviet withdrawal.

Reports suggest that it was only after a Saudi promise to supply 50,000 barrels of oil daily that PM Nawaz Sharif went ahead with the nuclear tests in 1998. Another report, possibly referring to the same commitment, says that oil was provided on the basis of deferred payment for three years and some of these payments were then written off. There was again a supply of free or concessional oil after this when we went cap in hand to overcome a balance of payment problems. Most recently, and perhaps the only financial support publicly acknowledged, were the 1.5 billion dollars that the Nawaz Sharif government received after it took power in 2013. I believe that putting all this together, the Saudi contributions over the years, has amounted at today’s prices to more than $25 billion.

Politically they and the UAE joined us in being the only countries to recognise the Taliban regime and to offer them some financial support. What did they get in return? (i) High quality training facilities in our military establishments; (ii) in Zia’s time the deputation of a contingent for internal security duties after the 1979 mosque seizure by dissident Saudis; (iii) in 1991, when they feared, perhaps wrongly, a possible Iraqi invasion they asked for our troops. It was the era of Gen. Baig’s “strategic defiance”. It took us weeks (quite wrongly) to settle the financial terms for the dispatch of our contingent, which we (quite rightly) conditioned on the strict understanding that it would not be deployed on the Saudi border with Iraq; (iv) a refusal, despite all the pressure they brought to bear on Nawaz Sharif—who had been given asylum and funding in Saudi Arabia during his exile—by the Pakistani parliament to countenance participation in the Yemen war which has become an albatross for the new Saudi leadership.

In international relations, as in our own day-to-day relations, there are no free lunches. Perhaps the Saudis have the right to feel that they got the raw end of the deal by getting little return for their largesse. But is this the whole story?

While the Saudis have refused to comment on the many stories that emerged in the WikiLeaks release of an avalanche of State Department telegrams and reports, there were many that referred to the Saudi-Pak relationship. The current foreign minister is quoted as telling the State Department in 2007 when he was the Saudi ambassador in the US that, “We in Saudi Arabia are not observers in Pakistan, we are participants.” This, of course, was the Musharraf era. But even before that, the Saudi diplomats were called upon repeatedly by politicians to resolve an internal crisis starting, if memory serves correctly, with their mediatory efforts in PM Bhutto’s abortive attempt to reach an agreement with the Pakistan National Alliance. It is difficult to believe that that these efforts were entirely altruistic or that this “participation” did not serve what were perceived to be Saudi interests in Pakistan.

Even more significant in delineating the Saudi role in Pakistan were the WikiLeaks revelation of a cable from the US consul general sent in November 2008 in which he reported on his tour of Southern Punjab. It said, “a sophisticated jihadi recruitment network had been developed in the Multan, Bahawalpur, and Dera Ghazi Khan Divisions…to recruit children into the divisions’ growing Deobandi and Ahl-e-Hadith madrassa network from which they were indoctrinated into jihadi philosophy, deployed to regional training/indoctrination centres, and ultimately sent to terrorist training camps in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA)”. It went on to add, “Government and non-governmental sources claimed that financial support estimated at nearly 100 million USD annually was making its way to Deobandi and Ahl-e-Hadith clerics in the region from ‘missionary’ and ‘Islamic charitable’ organizations in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates ostensibly with the direct support of those governments.”

Is this figure unrealistic? The late King Fahd’s website, extolling his regime’s efforts to propagate the right version of Islam, says that: “Saudi scholars helped create and administer 200 Islamic colleges, 210 Islamic centres, 1,500 mosques and 2,000 schools for Muslim children in non-Muslim countries.” In a congressional testimony last year, Daniel Byman, an anti-terrorism expert, quoted US treasury officials as estimating that this effort cost upwards of $75 billion. Would it be unreasonable to assume that spending $100 million annually to influence a sensitive area in Pakistan would be compatible with what the website boasts?

The WikiLeaks release of Saudi documents in 2015 also had a story to tell about the Islamic University in Islamabad and the Saudi role in ensuring that the Pakistani head of the university be replaced by a Saudi “who is consistent with our orientation” after the Pakistanis had insisted on inviting the Iranian ambassador to the celebration of a cultural week on campus. This change of leadership was sanctioned by President Zardari.

It is perhaps not necessary to dwell on what the presence of the Imam-e-Kaaba at the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-F’s centenary celebrations last week and his meetings with our political leaders mean when it comes to gauging Saudi influence in Pakistan. But it is necessary to mention the Imam’s frequent reiteration of the anti-terror objectives of the proposed Islamic army.

And back to Iran...

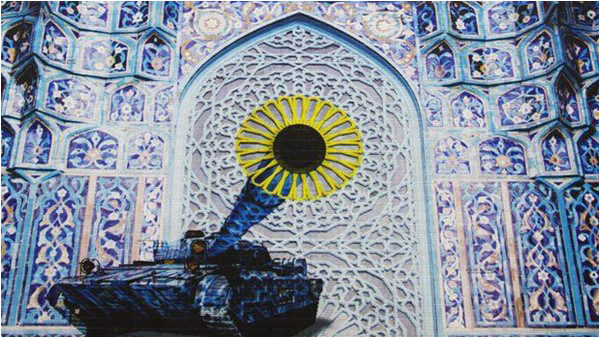

In discussing Iran-Pakistan relations, one must start by noting that Iran was the first country to recognize Pakistan, a fact often mentioned to illustrate the difference between this neighbour to the West and our other neighbour to the Northwest. The border between the two countries is demarcated and settled. Both took pride in the close cooperation (political and economic) which characterised relations with the Shah’s Iran. It included unstinting assistance during our war with India in 1965 and the provision of “strategic depth” (this is where the phrase entered the lexicon of our security establishment) by allowing our aircraft to use Shiraz and Isfahan air bases. It included common membership of the US-sponsored Baghdad Pact subsequently known as CENTO and as a sequence the Regional Cooperation for Development (RCD), visualised as an organisation that would promote trade and economic links between Turkey Iran and Pakistan. There was extensive and perhaps unwise cooperation as both countries contended with the unrest in what many Baloch people regarded as the two parts of one Balochistan.

All of this underwent a considerable change after the success of the Islamic Revolution. There was suspicion of Pakistan’s leadership at that time and of the cosy relationship Zia had sought to maintain with the Shah. In Pakistan, as in other Muslim countries, there was consternation when the new leaders issued clarion calls for the “export of the revolution” and the resonance this seemed to find in many parts of the Muslim world. Zia’s Islamisation programme, with its focus which appeared to be on the Saudi version of Islam, and some of his actions that were seen as anti-Shia, gave rise to new suspicions for a regime that regarded itself as the guardian of Shias wherever they were.

Pakistan was able to restore a measure of trust when it refused to be drawn in to taking sides in the Iran-Iraq war thrust upon the new regime by Saddam’s Iraq anxious to seek a reversal of the 1975 Algiers Accord under which Iraq had to cede areas in the Shatt-al Arab that had traditionally been Iraqi territory.

Pakistan was part of numerous mediatory efforts but carefully protected its neutrality. It did not, however, do much to prevent our religious leaders from both sects from receiving funding available from Iraq and Saudi Arabia on the one hand and from Iran on the other. This served to create a sectarian divide that we had never suffered before and to make Pakistan the secondary battlefield for the Iran-Iraq conflict.

Another consequence was differences on Afghanistan. It would take too long to explain how these differences arose within this space but suffice it to say that even today there is no meeting of minds on Afghanistan and the relations that the two countries should maintain on this issue.

We have a settled border but the Iranians have felt it necessary to build a three-foot-thick concrete wall all along its 780 kilometres. They fear human trafficking, and the use of territory in Pakistan’s Balochistan by groups such as Jundullah and Jashn-e-Adl to launch attacks on targets in Iran’s Sistan and Baluchestan province.

Everyone acknowledges that the potential for trade between the two countries is great. Both have committed to raising annual trade to $5 billion. Both say they are anxious to bring to fruition the agreement signed for bringing Iranian gas to Pakistan and then perhaps on to India. But Pakistan has not built the pipeline on its side and the Iranians too are obviously waiting for Pakistan to do so before building the 70-80km long fork from their 56-inch pipeline, built to supply Sistan and Baluchestan, to the Pakistan border. Both have talked of the potential of the ECO. (The expanded RCD now has 10 members.) The Central Asian States and Afghanistan were added in 1992 but no concrete steps have been taken, the ECO summit in Islamabad notwithstanding.

Both have downplayed the border clashes that have occurred or the landing of Iranian artillery shells on Pakistan territory as trigger-happy Iranian soldiers contend with dissident groups who they say flee into Pakistan.

While Pakistan was vocal about the Indian spy who managed to use Iran as a base for his operations over an extended period against Pakistan it has not taken up in any form, as far as one can see, the fact that some 10,000 or more Pakistanis have been recruited from Pakistan along with a similar number of Afghans to serve in Iran’s Zainabuyon brigades in Syria.

Both countries are aware that smuggling on a large scale is taking place. It is instructive that according to the media, based largely on official briefings, 0.7 million litres of petrol or 15% to 20% of total consumption in Pakistan is being smuggled from Iran. A police superintendent was charged in September 2015 with earning about one million rupees a month for providing cover to this nefarious trade. There has been no indication that since then the flow of this petrol has abated.

It is apparent, however, that both sides want at this time to accentuate the positive. A close perusal of the official Iranian news agency coverage of Pak-Iran relations recalls that President Rouhani has visited Pakistan twice during the last year and there have been numerous exchanges of visits and exhibitions in this period. The problems that exist barely secure mention.

This is mature diplomacy. Iran does not need any problems on this border.

The more urgent problem is, however, to my mind on our side. Assuming, as I have done, that Iran is not averse to Pakistan attempting to bridge the divide between Iran and Saudi Arabia, we do need to recognise that the issues that could bedevil relations between the two countries relate to poor governance and can be rectified at our end. We can then demand that Iran fix its governance structures also.

(This is the last analysis of a two-part series. The first part was published in the April 7-13 edition and was titled, ‘The Iran that came out of the Cold’.)

The writer is a former foreign secretary and has served as ambassador to the US and Iran, among other key appointments. He lectures at NDU and has written extensively on Pakistan and international relations.

It was our clerics on both sides of the communal divide who unhesitatingly accepted the free flow of funds from Saudi Arabia and Iraq on the one hand and from Iran on the other. They created a communal divide of which we had been mercifully free and they made us the secondary battlefield of the Iran-Iraq war.

We should also be clear that the evils we attribute to Saudi influence in Pakistan were the doing of our leaders. That we felt the full blast of the Saudi effort to spread the Wahabi creed beyond the kingdom's boundaries is undeniable but let us not forget the culpability of our own leaders

I have not researched this to the extent I would have liked, but I think that if we look back we will find that the urge to spread the Wahabi creed beyond the boundaries of Saudi Arabia reared its head only after the Iran-Iraq war when a monarchy threatened by internal dissension became even more beholden to the Saudi clergy schooled in Wahabism. That we felt the full blast of the Saudi effort is undeniable—but let us not forget the culpability of our own leaders.

Saudi largesse was in short supply during the periods of Pakistan Peoples Party rule but it flowed plentifully in other eras be they of Nawaz Sharif or military rule. The Saudis contributed (quietly as has been their wont) $500 million for our initial purchase of F-16s in 1981-82. The Saudis matched every CIA dollar for the Afghan war and spent perhaps more than $5 billion. Apart from this, the Saudi ambassador received vast sums of money from private Saudi Zakat donors for Afghan jihad and distributed it, through our agencies, in consultation with Pakistani officials. These funds remained available for some time after the Soviet withdrawal.

Reports suggest that it was only after a Saudi promise to supply 50,000 barrels of oil daily that PM Nawaz Sharif went ahead with the nuclear tests in 1998. Another report, possibly referring to the same commitment, says that oil was provided on the basis of deferred payment for three years and some of these payments were then written off. There was again a supply of free or concessional oil after this when we went cap in hand to overcome a balance of payment problems. Most recently, and perhaps the only financial support publicly acknowledged, were the 1.5 billion dollars that the Nawaz Sharif government received after it took power in 2013. I believe that putting all this together, the Saudi contributions over the years, has amounted at today’s prices to more than $25 billion.

I believe that putting all this together, the Saudi contributions over the years, has amounted at today's prices to more than $25 billion

Politically they and the UAE joined us in being the only countries to recognise the Taliban regime and to offer them some financial support. What did they get in return? (i) High quality training facilities in our military establishments; (ii) in Zia’s time the deputation of a contingent for internal security duties after the 1979 mosque seizure by dissident Saudis; (iii) in 1991, when they feared, perhaps wrongly, a possible Iraqi invasion they asked for our troops. It was the era of Gen. Baig’s “strategic defiance”. It took us weeks (quite wrongly) to settle the financial terms for the dispatch of our contingent, which we (quite rightly) conditioned on the strict understanding that it would not be deployed on the Saudi border with Iraq; (iv) a refusal, despite all the pressure they brought to bear on Nawaz Sharif—who had been given asylum and funding in Saudi Arabia during his exile—by the Pakistani parliament to countenance participation in the Yemen war which has become an albatross for the new Saudi leadership.

In international relations, as in our own day-to-day relations, there are no free lunches. Perhaps the Saudis have the right to feel that they got the raw end of the deal by getting little return for their largesse. But is this the whole story?

While the Saudis have refused to comment on the many stories that emerged in the WikiLeaks release of an avalanche of State Department telegrams and reports, there were many that referred to the Saudi-Pak relationship. The current foreign minister is quoted as telling the State Department in 2007 when he was the Saudi ambassador in the US that, “We in Saudi Arabia are not observers in Pakistan, we are participants.” This, of course, was the Musharraf era. But even before that, the Saudi diplomats were called upon repeatedly by politicians to resolve an internal crisis starting, if memory serves correctly, with their mediatory efforts in PM Bhutto’s abortive attempt to reach an agreement with the Pakistan National Alliance. It is difficult to believe that that these efforts were entirely altruistic or that this “participation” did not serve what were perceived to be Saudi interests in Pakistan.

Even more significant in delineating the Saudi role in Pakistan were the WikiLeaks revelation of a cable from the US consul general sent in November 2008 in which he reported on his tour of Southern Punjab. It said, “a sophisticated jihadi recruitment network had been developed in the Multan, Bahawalpur, and Dera Ghazi Khan Divisions…to recruit children into the divisions’ growing Deobandi and Ahl-e-Hadith madrassa network from which they were indoctrinated into jihadi philosophy, deployed to regional training/indoctrination centres, and ultimately sent to terrorist training camps in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA)”. It went on to add, “Government and non-governmental sources claimed that financial support estimated at nearly 100 million USD annually was making its way to Deobandi and Ahl-e-Hadith clerics in the region from ‘missionary’ and ‘Islamic charitable’ organizations in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates ostensibly with the direct support of those governments.”

Is this figure unrealistic? The late King Fahd’s website, extolling his regime’s efforts to propagate the right version of Islam, says that: “Saudi scholars helped create and administer 200 Islamic colleges, 210 Islamic centres, 1,500 mosques and 2,000 schools for Muslim children in non-Muslim countries.” In a congressional testimony last year, Daniel Byman, an anti-terrorism expert, quoted US treasury officials as estimating that this effort cost upwards of $75 billion. Would it be unreasonable to assume that spending $100 million annually to influence a sensitive area in Pakistan would be compatible with what the website boasts?

The WikiLeaks release of Saudi documents in 2015 also had a story to tell about the Islamic University in Islamabad and the Saudi role in ensuring that the Pakistani head of the university be replaced by a Saudi “who is consistent with our orientation” after the Pakistanis had insisted on inviting the Iranian ambassador to the celebration of a cultural week on campus. This change of leadership was sanctioned by President Zardari.

It is perhaps not necessary to dwell on what the presence of the Imam-e-Kaaba at the Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-F’s centenary celebrations last week and his meetings with our political leaders mean when it comes to gauging Saudi influence in Pakistan. But it is necessary to mention the Imam’s frequent reiteration of the anti-terror objectives of the proposed Islamic army.

And back to Iran...

In discussing Iran-Pakistan relations, one must start by noting that Iran was the first country to recognize Pakistan, a fact often mentioned to illustrate the difference between this neighbour to the West and our other neighbour to the Northwest. The border between the two countries is demarcated and settled. Both took pride in the close cooperation (political and economic) which characterised relations with the Shah’s Iran. It included unstinting assistance during our war with India in 1965 and the provision of “strategic depth” (this is where the phrase entered the lexicon of our security establishment) by allowing our aircraft to use Shiraz and Isfahan air bases. It included common membership of the US-sponsored Baghdad Pact subsequently known as CENTO and as a sequence the Regional Cooperation for Development (RCD), visualised as an organisation that would promote trade and economic links between Turkey Iran and Pakistan. There was extensive and perhaps unwise cooperation as both countries contended with the unrest in what many Baloch people regarded as the two parts of one Balochistan.

All of this underwent a considerable change after the success of the Islamic Revolution. There was suspicion of Pakistan’s leadership at that time and of the cosy relationship Zia had sought to maintain with the Shah. In Pakistan, as in other Muslim countries, there was consternation when the new leaders issued clarion calls for the “export of the revolution” and the resonance this seemed to find in many parts of the Muslim world. Zia’s Islamisation programme, with its focus which appeared to be on the Saudi version of Islam, and some of his actions that were seen as anti-Shia, gave rise to new suspicions for a regime that regarded itself as the guardian of Shias wherever they were.

Pakistan was able to restore a measure of trust when it refused to be drawn in to taking sides in the Iran-Iraq war thrust upon the new regime by Saddam’s Iraq anxious to seek a reversal of the 1975 Algiers Accord under which Iraq had to cede areas in the Shatt-al Arab that had traditionally been Iraqi territory.

Pakistan was part of numerous mediatory efforts but carefully protected its neutrality. It did not, however, do much to prevent our religious leaders from both sects from receiving funding available from Iraq and Saudi Arabia on the one hand and from Iran on the other. This served to create a sectarian divide that we had never suffered before and to make Pakistan the secondary battlefield for the Iran-Iraq conflict.

Saudi diplomats were called upon repeatedly by politicians to resolve an internal crisis starting, if memory serves correctly, with their mediatory efforts in PM Bhutto's abortive attempt to reach an agreement with the Pakistan National Alliance. It is difficult to believe that that these efforts were entirely altruistic or that this "participation" did not serve what were perceived to be Saudi interests in Pakistan

Another consequence was differences on Afghanistan. It would take too long to explain how these differences arose within this space but suffice it to say that even today there is no meeting of minds on Afghanistan and the relations that the two countries should maintain on this issue.

We have a settled border but the Iranians have felt it necessary to build a three-foot-thick concrete wall all along its 780 kilometres. They fear human trafficking, and the use of territory in Pakistan’s Balochistan by groups such as Jundullah and Jashn-e-Adl to launch attacks on targets in Iran’s Sistan and Baluchestan province.

Everyone acknowledges that the potential for trade between the two countries is great. Both have committed to raising annual trade to $5 billion. Both say they are anxious to bring to fruition the agreement signed for bringing Iranian gas to Pakistan and then perhaps on to India. But Pakistan has not built the pipeline on its side and the Iranians too are obviously waiting for Pakistan to do so before building the 70-80km long fork from their 56-inch pipeline, built to supply Sistan and Baluchestan, to the Pakistan border. Both have talked of the potential of the ECO. (The expanded RCD now has 10 members.) The Central Asian States and Afghanistan were added in 1992 but no concrete steps have been taken, the ECO summit in Islamabad notwithstanding.

Both have downplayed the border clashes that have occurred or the landing of Iranian artillery shells on Pakistan territory as trigger-happy Iranian soldiers contend with dissident groups who they say flee into Pakistan.

While Pakistan was vocal about the Indian spy who managed to use Iran as a base for his operations over an extended period against Pakistan it has not taken up in any form, as far as one can see, the fact that some 10,000 or more Pakistanis have been recruited from Pakistan along with a similar number of Afghans to serve in Iran’s Zainabuyon brigades in Syria.

Both countries are aware that smuggling on a large scale is taking place. It is instructive that according to the media, based largely on official briefings, 0.7 million litres of petrol or 15% to 20% of total consumption in Pakistan is being smuggled from Iran. A police superintendent was charged in September 2015 with earning about one million rupees a month for providing cover to this nefarious trade. There has been no indication that since then the flow of this petrol has abated.

It is apparent, however, that both sides want at this time to accentuate the positive. A close perusal of the official Iranian news agency coverage of Pak-Iran relations recalls that President Rouhani has visited Pakistan twice during the last year and there have been numerous exchanges of visits and exhibitions in this period. The problems that exist barely secure mention.

This is mature diplomacy. Iran does not need any problems on this border.

The more urgent problem is, however, to my mind on our side. Assuming, as I have done, that Iran is not averse to Pakistan attempting to bridge the divide between Iran and Saudi Arabia, we do need to recognise that the issues that could bedevil relations between the two countries relate to poor governance and can be rectified at our end. We can then demand that Iran fix its governance structures also.

(This is the last analysis of a two-part series. The first part was published in the April 7-13 edition and was titled, ‘The Iran that came out of the Cold’.)

The writer is a former foreign secretary and has served as ambassador to the US and Iran, among other key appointments. He lectures at NDU and has written extensively on Pakistan and international relations.