It is the mid-19th century. In a neighbourhood of Lucknow in northern Hindustan a young motherless girl invokes her father to get her a hill myna. The father Kalay Khan is the caretaker of birds kept in the enormous, ornate, inventive and beautifully wrought royal cage called Aijadi Qafas wherein dwell 40 such birds. Birds renowned for their ability to emulate the human voice and recite beautifully what they hear or are taught. The indulgent father gives in and smuggles out one of the birds for her. However, when he eventually returns it to the cage he gets caught out as the bird recites in the presence of the King and foreign dignitaries the homely verse the little girl had taught her; rather than the elaborate and literary utterances that the rest of the forty were taught to speak. The cage (Qafas is so much more evocative) is located in the Taoos Chaman (the peacock shaped garden — one amongst many laid out in the shapes of animals) laid out by the music, literature, art, knowledge, animal and garden loving Wajid Ali Shah - the last King of the northern state of Awadh. Nawab Wajid Ali Shah is as staunchly benevolent and empathetic as he is ardently aesthetic and epicurean. The transgression is forgiven in a manner that truly epitomises the Nawab’s grace (the edict is exquisite) but Kalay Khan nevertheless finds himself embroiled in palace intrigue. Meanwhile, the Company Bahadur is looking for every excuse to depose Wajid Ali Shah and in 1856 the British usurp Awadh and exile the King.

This story — called Taus Chaman Ki Maina — was initially written by the distinctive Lucknow based Urdu writer Nayyer Masood. Anees Ashfaq's novel is both an elaboration as well as an extension of the same which both prefaces it and also tells what happens half a century later as his protagonist endeavours to excavate and find further details of this half-remembered tale. At the same time, Pari Naaz aur Parinde is a brooding contemplation of a bygone era, a nostalgic evocation of historic Lucknow, and a subtle but impactful post-colonial deconstruction of the idea that Muslim rule in Hindustan was disrupted and displaced because it was decadent and ineffectual.

One grew up watching Satyajit Ray's memorable cinematography of Munshi Prem Chand's story Shatranj Ke Khilari. Amjad Khan’s portrayal of the last Nawab is sensitive and compelling but the ultimate image that one carries is of a sensual and ineffective ruler. Pari Naaz aur Parinde counters this depiction of Wajid Ali Shah in Prem Chand and Ray's imaginings and portrayals. Maligning and misrepresenting and at the same time actively undermining to create additional reasons for maligning and misrepresenting were tactics honed to perfection by the rapacious British colonial empire. Accusing native rulers of misrule, the Doctrine of Lapse was then used to annex many kingdoms including Awadh. In his brilliant magnum opus Kai Chand the Sar e Aasman and also his wonderful earlier stories compiled under Sawaar aur Deegar Afsanay Shams ur Rehman Farooqi demystifies the heady tilism of the fables of decadence and decay of native empires. He showcases how Hindustan was at the pinnacle of its cultural, artistic, and societal achievements and by no stretch facing civilisational decline when foreign powers imposed their hegemony. The political turbulence of the time, on the other hand, was as much if not more an outcome of the machinations and debilitating intrigue of those intent on bringing indigenous rulers down, most notably that of the British, as it was a manifestation of the ageing and particular phase of the empire and ineptitude of sections of its ruling elites.

Pari Naaz aur Parinde provides multiple insights into the cultural milieu and political mood of Wajid Ali Shah’s Awadh, highlighting the meticulousness, popularity and largesse of his rule, and reminding of the connivance and conspiracies that led to his fall. The novel powerfully evokes a time and age of peace, tolerance, public works, charity, urban sophistication and artistic flowering, that could not withstand the blunt and boorish expansionism of the Raj.

Anis Ashfaq’s narrative walks us through many Lucknows — the physical Lucknow with its famous but neglected gardens and crumbling neighbourhoods (as he does in his novel Dukhiyare); the imagined Lucknow with its past glory and grandeur; the lived Lucknow with its mannerisms and charms; and the longed-for Lucknow

There are lots of birds in Pari Naz aur Parinde. And sprawling gardens, parks for wild animals, and vast tracks of open jungle and waterways outside the Lucknow of mid-nineteenth century with sections surviving even half a century later. And also, old denizens of the once glorious city, who like their civilisation face decline and decay. One such character – an aristocratic compiler and writer of dastans – is styled after Nayyer Masud himself. Anis Ashfaq’s young protagonist Shaheen Sheherzad is appropriately named for a novel teeming with birds and lost stories. He is a flaneur, with time at his hands and the patience to track down lost stories as well as a mysterious girl who fashions and sells exquisite birdcages. For those hardwired by modern life that only allows short spurts of attention and fleeting and flickering images of life; the ones who always look for a tight plot and a definite story and a clear ending, the poetic and allegorical quality of this novel will be utterly lost. Yes, it meanders and moves without a care and sometimes appears to be lost like a narrow brook on the overgrown forest floor. Yes, the young protagonist; the birdcage girl Farash Ara, her mother Falak Ara (how fortunes change; the mother’s name begets an aspiration for the sky whereas the daughter is more humbly earthbound); the wandering, nature conserving, remembering, philosophising, bird-feeding old man Hussain Aabdar; the gracious nobleman Prince Yousaf Mirza and his elegant spouse Sultan Jahan urf Aalia Begum; the gracious Bahoo Begum; the principled Darogha Nabi Bakhsh; Ram Din the bird seller and various other characters at times appear dreamy and speak as if in a trance. But then the book is ultimately an excavation of a time and place that has more or less faded away. A time and place being assembled through a fragment of a memory here and a broken Almas Khani brick there. Without periodic escapes to a more dream-like plane and without resort to symbolic and implicit modes of observance and communication how does one recollect, recreate and convey all this. And how does one actually live through and survive the recollection of all this? In a Lucknow firmly under British rule at the end of the nineteenth century? A Lucknow turning into ruins, its rulers long forced out but still mocked by the intruders, and its culture, norms and way of life struggling to survive all that assails it. And being recollected by characters who feel the pain of themselves diminishing as their city diminishes.

Anis Ashfaq’s narrative walks us through many Lucknows — the physical Lucknow with its famous but neglected gardens and crumbling neighbourhoods (as he does in his novel Dukhiyare); the imagined Lucknow with its past glory and grandeur; the lived Lucknow with its mannerisms and charms; and the longed-for Lucknow with the wistful envisioning of what it could have been. Such walks are too painful, contemplative and multi-dimensional to be undertaken merely with eyes wide open, stick in hand, and the avid gaze of a tourist. These are deeply melancholic walks that take their emotional toll. I should know for I too have walked through and written about a dying city. Such walks mandate introspection, imagination and feeling. Outwardly they are often aimless, seemingly self-indulgent and perhaps a bit like sleepwalking. That is because the sights one seeks often lie within rather than without.

Influenced by Attar’s Conference of the Birds, the Alif Laila tradition, the dastans and qissas that sprouted in that city of qissas, gardens, bird lovers, good manners and haunted mansions — Lucknow, and the writings of Nayyer Masood, this novel nevertheless carries the distinctive characteristics of Anis Ashfaq’s understated storytelling. The charm of Lucknow’s manner of speech, special idiom and urbane mannerisms reflects all through - and lends added poignance to this heartfelt lament for the loss of a city and a civilisation. Amidst the all-enveloping gloom of loss there are at times flashes of humour. The hill mynas and other birds all have names and distinct personalities, cherished by those who could discern and appreciate such differences of personalities. One can’t escape the troubling and fatalistic thought that a culture that attached such value to caring for and treasuring birds was never equipped to withstand the rowdy march of harder men with meaner aims. This indeed has been the bane of human history.

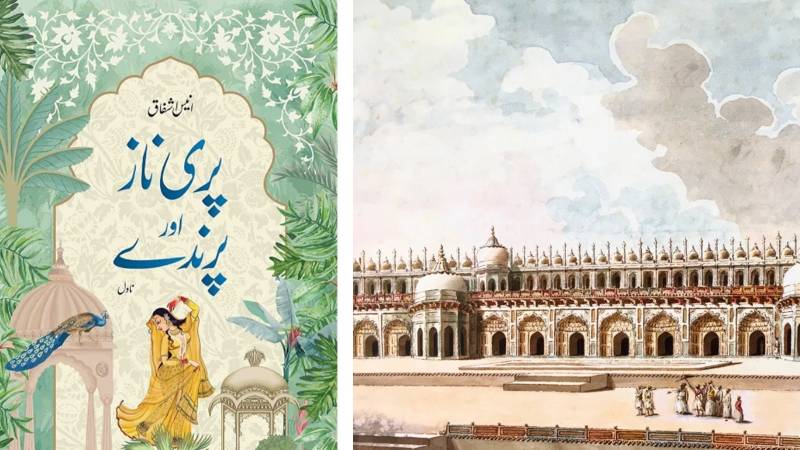

Published in India in 2018, this Pakistani edition published earlier this year by Book Corner Jhelum is as aesthetically pleasing as the book itself.