I was startled to read on Friday, in press accounts of the Pakistan Supreme Court’s decision to uphold the 21st Amendment, two comments indicating that the decision also upheld The Doctrine of Necessity. This was surprising for two reasons: first, I thought the Doctrine of Necessity was dead and buried—at least that is what former Chief Justice Iftekhar Chaudhry thought it deserved in 2009; and second, I saw little connection between a concept that was based on the idea that domestic emergency could override constitutional guarantees of rights, and the questions of due process and equal treatment under the law, in addition to the structural constitutional ones that seemed central to whether the 21stAmendment violated the Constitution.

But a former President of the Pakistan Supreme Court Bar Association, Kamran Murtaza was quoted as saying, inter alia, “The court just upheld the doctrine of necessity….” This provoked me to scour the internet for articles on the decision. I soon came across a statement by the International Commission of Jurists condemning the decision. Sam Zarifi, speaking for the ICJ, said “impeding the right to a fair trial cannot be justified on the basis of the public emergency or the ‘doctrine of necessity’….”

These two statements were the only two I could find that mentioned the Doctrine of Necessity, but both are very credible, and they quickly sent me to the text of the decision, which surprisingly, is already posted on the internet. That version, however, turns out to be over 400 pages, and I would need much more time than I have even to skim it to find any discussion of the Doctrine of Necessity as a factor in the Court’s decision. I would like to say that I skimmed it, but the truth is that I skipped through it, and thus passed over large swatches of pages, and even then, late last night, fell asleep while skipping through it.

In the text, I did see some discussion of the definition of war and whether the so-called “war on terror” is a war or an insurgency. There is, in international law, the concept of a “just war,” divided into two questions: the reasons it is allowable to start a war; and how a just war must be fought. As far as I can tell from my very limited understanding of this concept, both sets of rules are honored almost totally in the breach. So if the court decided that the “war” against the Taliban and other extremists is a just war, I suppose it could then use the Doctrine of Necessity to justify shortcutting some of the constitutional guarantees regarding due process and equal/fair treatment in the interests of the “necessity” to win the war against extremism.

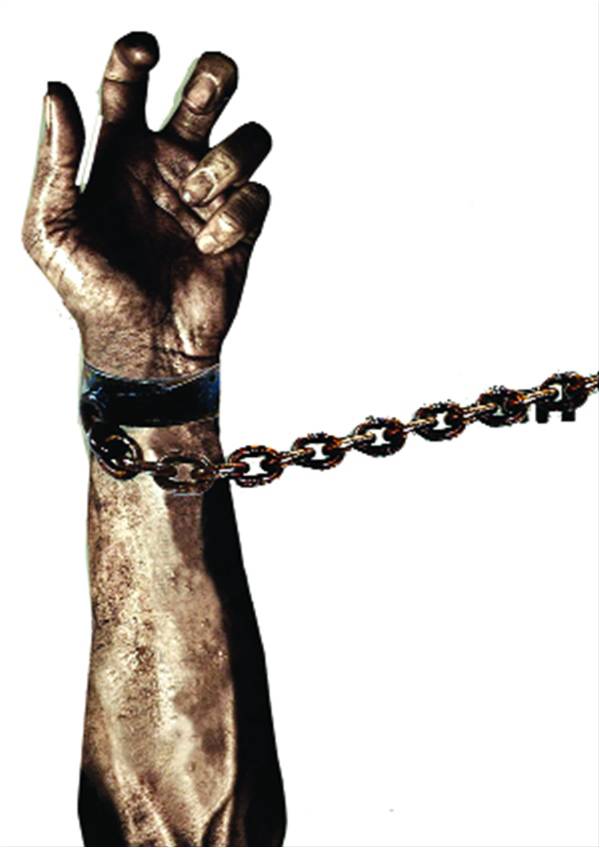

Readers will be familiar with the Doctrine of Necessity, as for most it has affected their lives very directly. It has been used by the courts of Pakistan to justify the “extra-legal” military takeovers of the state from civilian authorities. For the most part, these takeovers have been upheld by the courts because they were said to be necessary to restore order. This specific type of “necessity” of goes back to the writings of a medieval jurist, Henry de Bracton, and is essentially a doctrine of “that which is otherwise not lawful is made lawful by necessity.” But, of course, the catch is who decides what is necessary? In Pakistan, this was the military or those close to it who distrusted elected politicians.

Though used occasionally from medieval times, perhaps as early the 13th century, it became more fashionable after it was used to justify the 1954 use of emergency powers by Pakistan’s Governor-General, Ghulam Mohammad, to dismiss the Constituent Assembly and the Council of Ministers. He claimed they did not represent the people of Pakistan—as if he did. This was challenged in court but the Chief Court of Pakistan upheld the Governor-General’s action, citing a more compelling version of the Doctrine of Necessity, “the well-being of the people is the supreme law.” But, of course, the catch, then as now, is who gets to decide what best serves the welfare of the people. Since then this doctrine has regularly appeared in court to justify court decisions that validate military seizures of power in Pakistan and in many of the other developing counties in which the military has acted outside the constitution to take power.

But the Doctrine of Necessity has not been absent from the courts of developed countries in times of emergency. The US record is far from unblemished although from the 1850s, while the US Supreme Court recognized that State and Federal governments may necessarily infringe on civil rights and liberties during an emergency, be it war, insurrection, economic or natural disaster, it has insisted that their response must not exceed what is necessary. The court has approved a number of such infringements, but has rejected deference to the executive branch in deciding if the actions taken or contemplated are necessary. This it evaluates on its own.

The case that still brings deep pangs of guilt to most Americans is the internment of Japanese-American citizens living on the West Coast during the Second World War. This was contested in court, and it was upheld, after evaluation by the court that it was necessary. Most of us now realize that the court, and the Executive Branch, made a horrible mistake on this case, and the apologies and compensation cannot ever atone completely for this failure of nerve. Having grown up with many Nisei who spent their early childhoods in internment camps, I remain acutely conscious of that ugly stain on the US human rights record.

Nonetheless, even during the most severe emergencies the US court has refused to allow military trials of citizens. This was first rejected during the civil war in a case that came to the court from Indiana, and reaffirmed as late as World War 2 in a case involving a Japanese-American from Hawaii, almost the front line. Nor has the court ever upheld measures in any emergency that affect the separation of powers between the 3 branches of government. The court understands that when confronted by an emergency, the executive and the legislative branches are very likely to forget about civil and individual rights, and to skip the niceties of the legislative process, but their fears cannot be sufficient legal basis for violating the constitution. No emergency can abridge the fundamental rules of governance set out by the constitution.

When carefully and narrowly applied, the Doctrine of Necessity can strengthen the rule of law. When expansively applied, it can transform naked power into legal authority. What the recent decision on the 21st Amendment will mean is yet to be seen. But I wish I could discern some effort by the civilian government to be ready when the sunset provision of the Amendment kicks in. Will the civilian anti-terrorist courts, created with such fanfare 15 or so years ago, be reorganized and beefed up to take over handing out justice to terrorists? I don’t see much evidence of that right now—and time’s a wastin’.

But a former President of the Pakistan Supreme Court Bar Association, Kamran Murtaza was quoted as saying, inter alia, “The court just upheld the doctrine of necessity….” This provoked me to scour the internet for articles on the decision. I soon came across a statement by the International Commission of Jurists condemning the decision. Sam Zarifi, speaking for the ICJ, said “impeding the right to a fair trial cannot be justified on the basis of the public emergency or the ‘doctrine of necessity’….”

These two statements were the only two I could find that mentioned the Doctrine of Necessity, but both are very credible, and they quickly sent me to the text of the decision, which surprisingly, is already posted on the internet. That version, however, turns out to be over 400 pages, and I would need much more time than I have even to skim it to find any discussion of the Doctrine of Necessity as a factor in the Court’s decision. I would like to say that I skimmed it, but the truth is that I skipped through it, and thus passed over large swatches of pages, and even then, late last night, fell asleep while skipping through it.

The US record is far from unblemished

In the text, I did see some discussion of the definition of war and whether the so-called “war on terror” is a war or an insurgency. There is, in international law, the concept of a “just war,” divided into two questions: the reasons it is allowable to start a war; and how a just war must be fought. As far as I can tell from my very limited understanding of this concept, both sets of rules are honored almost totally in the breach. So if the court decided that the “war” against the Taliban and other extremists is a just war, I suppose it could then use the Doctrine of Necessity to justify shortcutting some of the constitutional guarantees regarding due process and equal/fair treatment in the interests of the “necessity” to win the war against extremism.

Readers will be familiar with the Doctrine of Necessity, as for most it has affected their lives very directly. It has been used by the courts of Pakistan to justify the “extra-legal” military takeovers of the state from civilian authorities. For the most part, these takeovers have been upheld by the courts because they were said to be necessary to restore order. This specific type of “necessity” of goes back to the writings of a medieval jurist, Henry de Bracton, and is essentially a doctrine of “that which is otherwise not lawful is made lawful by necessity.” But, of course, the catch is who decides what is necessary? In Pakistan, this was the military or those close to it who distrusted elected politicians.

Though used occasionally from medieval times, perhaps as early the 13th century, it became more fashionable after it was used to justify the 1954 use of emergency powers by Pakistan’s Governor-General, Ghulam Mohammad, to dismiss the Constituent Assembly and the Council of Ministers. He claimed they did not represent the people of Pakistan—as if he did. This was challenged in court but the Chief Court of Pakistan upheld the Governor-General’s action, citing a more compelling version of the Doctrine of Necessity, “the well-being of the people is the supreme law.” But, of course, the catch, then as now, is who gets to decide what best serves the welfare of the people. Since then this doctrine has regularly appeared in court to justify court decisions that validate military seizures of power in Pakistan and in many of the other developing counties in which the military has acted outside the constitution to take power.

But the Doctrine of Necessity has not been absent from the courts of developed countries in times of emergency. The US record is far from unblemished although from the 1850s, while the US Supreme Court recognized that State and Federal governments may necessarily infringe on civil rights and liberties during an emergency, be it war, insurrection, economic or natural disaster, it has insisted that their response must not exceed what is necessary. The court has approved a number of such infringements, but has rejected deference to the executive branch in deciding if the actions taken or contemplated are necessary. This it evaluates on its own.

The case that still brings deep pangs of guilt to most Americans is the internment of Japanese-American citizens living on the West Coast during the Second World War. This was contested in court, and it was upheld, after evaluation by the court that it was necessary. Most of us now realize that the court, and the Executive Branch, made a horrible mistake on this case, and the apologies and compensation cannot ever atone completely for this failure of nerve. Having grown up with many Nisei who spent their early childhoods in internment camps, I remain acutely conscious of that ugly stain on the US human rights record.

Nonetheless, even during the most severe emergencies the US court has refused to allow military trials of citizens. This was first rejected during the civil war in a case that came to the court from Indiana, and reaffirmed as late as World War 2 in a case involving a Japanese-American from Hawaii, almost the front line. Nor has the court ever upheld measures in any emergency that affect the separation of powers between the 3 branches of government. The court understands that when confronted by an emergency, the executive and the legislative branches are very likely to forget about civil and individual rights, and to skip the niceties of the legislative process, but their fears cannot be sufficient legal basis for violating the constitution. No emergency can abridge the fundamental rules of governance set out by the constitution.

When carefully and narrowly applied, the Doctrine of Necessity can strengthen the rule of law. When expansively applied, it can transform naked power into legal authority. What the recent decision on the 21st Amendment will mean is yet to be seen. But I wish I could discern some effort by the civilian government to be ready when the sunset provision of the Amendment kicks in. Will the civilian anti-terrorist courts, created with such fanfare 15 or so years ago, be reorganized and beefed up to take over handing out justice to terrorists? I don’t see much evidence of that right now—and time’s a wastin’.