As the sun set on the British Raj in the Indian Subcontinent, women's voices began to resonate in the chorus of popular nationalism. Pioneering the way was Annie Besant, an English theosophist, alongside other Indian luminaries like Sarojini Naidu, Ruttie Jinnah, Kasturba Gandhi, Kamla Nehru, Indira Gandhi, and Aruna Asaf Ali.

The engagement of Muslim women, however, remained relatively subdued until the 1930s. The ascendancy of Aligarh-style Muslim nationalism, built upon the pillars of modernity and reform, catalysed a transformative shift in Muslim attitudes towards women’s participation in politics.

The Muslim League's groundbreaking resolution in 1932, which unequivocally pledged political equality for women, marked a watershed moment. This move wasn't just politically expedient but was rooted in a deep ideological commitment. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, having played a role in Women’s Suffrage movement as a student in London in the 1890s, recognized the indispensable contribution of women to national progress:

"No nation can rise to the height of glory unless your women are side by side with you... It is a crime against humanity that our women are shut up within the four walls of the houses as prisoners."

For Jinnah this was more than just political rhetoric. He ensured that his sister, Fatima Jinnah, stood steadfastly by his side during his political endeavors, a calculated choice that demonstrated his commitment to bringing women into the mainstream. He understood that women's participation meant a larger voting bloc and a heightened agitation for the cause.

When Punjab brimmed with the fervor of the civil disobedience movement, it was women who led the charge, undeterred by the constraints of purdah. In a single day, over 500 Muslim League women courted arrest, a testament to their determination. A defining moment came when Fatima Sughra scaled the walls of the Lahore secretariat, discarding the Union Jack and unfurling the Muslim League flag. Her act epitomised defiance in Punjab and the North West Frontier Province (NWFP).

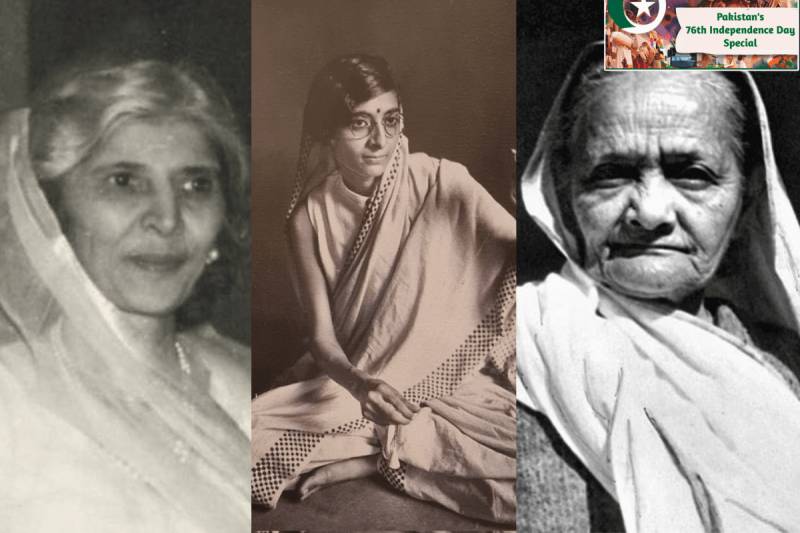

For young Muslim women like Mumtaz Shahnawaz, Shaista Ikramullah, and Salma Tassadaque, the Pakistan movement symbolized a conduit to their political and social empowerment. The era's literature and memoirs capture their aspirations. Shaista Ikramullah's "Purdah to Parliament" portrays the shift of Muslim women from seclusion to active political engagement, while Mumtaz Shahnawaz's novel "The Heart Divided" echoes the desires of women in the Pakistan movement.

Recognising the transformative potential of women, the Muslim League leadership entrusted women leaguers with the task of disseminating their message into the masses. Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan, at Jinnah's behest, established the Muslim Women's National Guard, a body of women that very passionately discarded the Purdah. Jinnah's modernist philosophy led him to challenge traditional norms within the Muslim community, including the strict seclusion of women. In an interview with Weldon James of the Collier’s Weekly on August 25, 1947, he opined:

"The position of women is already equal in law to that of men... the institution of purdah, which is the result of tradition and not of the teachings of the Qur’an, will gradually disappear. In the modern state such a precaution is not necessary, and it is already on the way out."

Jinnah and Pakistan’s other founders were from the modernist extraction of Islam. Consequently, in the years following independence, Pakistani women surged forward, with each constitution (1956, 1962 and 1973) reaffirming gender equality and affirmative action for women.

In 1965, Fatima Jinnah defied norms to challenge General Ayub Khan's dictatorship. Though her presidential campaign garnered broad support, it was met with religiously fueled resistance. This setback revealed a discord between tradition and progress.

Significantly while several religious figures – including the otherwise retrogressive Maulana Maududi of Jamaat e Islami- supported Fatima Jinnah, others played into the hands of the military regime, which despite its modernist credentials, argued that Islam did not allow women to become heads of state and government.

It was General Zia-ul-Haq's era that marred the trajectory, with a series of regressive ordinances stifling progress on women’s issues including the Hudood Ordinance and the all important change to the Law of Evidence which made women half witnesses. The response by Pakistani women was robust. Figures like Asma Jahangir and Benazir Bhutto continued the struggle with Benazir Bhutto becoming the Muslim world’s first woman Prime Minister.

However progress has been patchy. The national narrative was hijacked by the Zia regime and the feminist dimension of the Pakistan Movement was downplayed. By casting Pakistan as an orthodox religious demand, which it was not, the regime marginalised minorities and women alike.

Religious elements, all of whom had opposed the creation of Pakistan, now became the arbiters of Pakistan’s “ideology” and “Islamic values”. New ideological frontiers were constructed with very little space for women and minorities within.

Pakistan needs to rekindle its original spirit by embracing the feminist legacy of the Pakistan Movement, dismantling the pernicious legacy of General Zia's rule, and forging a narrative that champions gender equality, modernity, and reform. Only then can Pakistan reclaim its momentum and fulfill its potential.