– Sahir Ludhianvi

The charge that Faiz Ahmed Faiz had belittled his own poetry by making it speak to the concerns of ordinary working people is nothing new. In fact, this is part and parcel of the long held belief, much cherished in certain circles that Art is (and should remain) the property of the ‘civilized’ (euphemism for the wealthy); that the ‘unwashed masses’ have no interest in, and no understanding of, the ‘Fine Arts’. The view that Art is for Art’s sake and it is not incumbent upon the artist to take any social or other external viewpoints into account in the creative process has been espoused by, among others, James Joyce, Proust, Gertrude Stein, DH Lawrence, and WB Yeats.

The followers of Aesthetics which included the likes of Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) argued that Art cannot be made subservient to religious, political or economic motives. This was a rebellion against the idea that Art, unlike ‘higher truths’ (according to Plato) or the ‘rational sciences’ (according to Hegel) is always secondary to other disciplines of knowledge. Their rebellion was also a struggle against the ‘Philistines’, those thought to despise or undervalue art, beauty, intellectual content, and spiritual values. This was also a revolt against those who would use art purely for monetary gain.

The slogan of ‘Art for Art’s sake’ was thus born as a rebellion both against those who sought to denigrate Art and place it in a position inferior to other disciplines of knowledge as well as those who would use art for profit.

Which brings us back to the art of poetry, specifically Faiz’s poetry of ‘protest’ and ‘activism’ that continues to distress some people so much. The specific cause of this distress is Faiz’s association with the All India Progressive Writers Association, first formed in 1936.

Beginnings

It is hard to believe that a slim volume of short stories titled ‘Angarey’ could create such a stir and even harder to understand how this work became the nucleus of the twentieth century’s most significant politico-literary movement in the subcontinent. When first published in Lucknow in 1932, ‘Angarey’ created a firestorm. There was an immediate outcry and only a few hundred copies had been printed before the booklet of ten short stories was banned by the British authorities under pressure from India’s leading Muslim clerics and conservative associations. Almost all printed copies were destroyed and the four authors of the collection, all Muslim, came under fierce attack for their criticism of religious orthodoxy, traditional social and sexual mores and the prevailing attitudes towards women and the poor.

The authors, Syed Sajjad Zaheer, Ahmad Ali, Rasheed Jahan and Mahmudduzzafar all belonged to what we could essentially call upper to upper middle class families. Sajjad Zaheer, one of the founders of the All India Progressive Writers Association was the son of Sir Syed Wazir Hasan, the Chief Justice of the Oudh High court. Ahmad Ali was the son of a mid-level civil servant who would go on to attend Aligarh University and Lucknow University, graduating with first class first honors in both B.A and M.A English. Rashid Jahan was a gynecologist whose father had founded a school for girls that was later affiliated with Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s Mohammaden Anglo-Oriental College. Mahmooduzzafar was the son of Sahibzada Saiduzzafar Khan, a prominent member of the ruling family of Rampur; a doctor and head of the medical college of Lucknow University.

That these four young friends would publish such a collection was remarkable enough. What made the ensuing furor even stranger was that the stories themselves were largely forgettable, possessing little literary or artistic merit. One commentator noted that “the book suffers from all the problems of early, polemical writing. Many of the stories are poorly conceived and the writing is a thin veneer for an angry, though important, political critique.” (Ahmed Ali. “A Night of Winter Rains.” The Annual of Urdu Studies). Sajjad Zaheer himself wrote in his autobiography ‘Roshnaai’ that “Most of the stories in this collection lacked depth and serenity…In some places, where the focus was on sexuality, the influence of DH Lawrence and James Joyce was apparent”.

The stories, though, were, quite clearly, meant to shock and provoke. Before Manto, Ismat Chughtai and Mira-ji, all of whom were condemned for their unseemly focus on matters considered ‘indecent’ in polite society, there were four young friends and their ‘Angarey’. For the writers, all of whom grew up in Muslim households, it cannot have been more obvious that their work would enrage Muslim opinion.

Consider this passage from “MahavatoN ki ek raat” (“A Night of Winter Rains “) by Ahmad Ali: “Dear God, have mercy. God is supposed to be with the poor, to help them, to hear their cries of pain. Am I not poor? Why doesn’t God hear me? Does God exist or not? And what is God, after all? Whatever He is, He is very cruel and extremely unjust…Why doesn’t He care about us? Why did He make us? To suffer through sorrows and withstand troubles? What kind of justice is this! Why are they rich and we’re poor? This will all be recompensed in the afterlife. That is what the maulvi always says. Whose afterlife? To hell with afterlives. My troubles are here and now, my needs are here and now.”

The most controversial of the stories was probably Sajjad Zaheer’s ‘Jannat ki bashaarat’ (‘Vision of Heaven’) about a preacher (married to a wife twenty years younger) who has a dream about the forbidden pleasures of houris in heaven.

As Carlo Coppola has noted, the significance of ‘Angarey’ lay not in its literary quality, which, as noted earlier, was rather poor, nor in its polemics against religion and society which were shrill and rather immature, but in the fact that ‘Angarey’ brought together the core group of individuals who would go on to lay the foundation of the ‘Progressive Writer’s Movement’ in the Indian subcontinent, revolutionizing Urdu literature and influencing its course over most of the twentieth century.

It was in Amritsar that Sajjad Zaheer first met Faiz, then a young lecturer at the MAO College, Amritsar where Sahibzada Mahmuduzzafar was the Vice-Principal and from there onwards Faiz played an important role in All India Progressive Writer’s Association, and his involvement in the organization shaped his own ideas and work decisively.

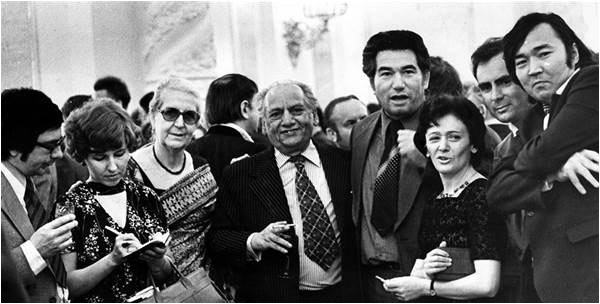

The All-India Progressive Writers’ Association was formed at the first conference of progressive writers in Lucknow in April 1936 and from thereon spread rapidly, encompassing the varied disciplines of literature, music, theater and cinema. According to Faiz’ biographer, the noted Russian scholar, Dr. Ludmila Vassilyeva, for three decades, the PWA remained an influential social and literary movement, comparable in scope to Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s Aligarh reformist movement.

Progressive Writers and the Left

Those who claimed that the AIPWA (All India Progressive Writers’ Association) was formed as a ‘front’ for the Communist Party of India’s political ambitions were either ignorant of the facts or, more likely, interested in maligning the organization as the British Raj attempted to do when it was first formed. Allama Iqbal, Bulbul-e-Hind Sarojni Naidu, Munshi Prem Chand (considered the founder of ‘realist’ literature in Urdu and Hindi); Josh Malihabadi (India’s most renowned poet after Muhammad Iqbal) and the distinguished linguist Maulvi Abdul Haq, all vigorously supported the idea of such a movement when first proposed by Sajjad Zaheer. Allama Iqbal and ‘Bulbul e Hind’ Sarojini Naidu were among those who put their signatures on the draft manifesto of the AIPWA circulated by Sajjad Zaheer. The keynote speaker at the second national conference of the AIPWA was none other than Rabindranath Tagore (Munshi Prem Chand had presided over the first conference of the organization).

[quote]Faiz refused to write patriotic songs in support of the Pakistan government during the 1965 war [/quote]

The idea that Faiz was somehow ‘pressured’ to go along with the ideology of the organization is laughable. Besides the fact that Faiz had a fierce independent streak (in spite of his outward reticence) as evidenced by, for example, his refusal to write patriotic songs in support of the Pakistan government during the 1965 war with India.

Here is Faiz himself on his association with the All India Progressive Writer’s Association: ‘During this time (in Amritsar), I met my friends Sahibzada Mahmuduzzafar and his wife Rashid Jahan. Then the Progressive Writer’s Association was born, the workers’ movements started and it felt as if new gardens of experience (‘dabistan’) had opened up. During this, the first lesson I learned was that one’s own self is a very insignificant thing in the larger scheme of the universe and it is both fruitless and futile to focus on it to the exclusion of the larger world outside’ (Nuskha Hai Wafa—Faiz).

Faiz never wavered from this point of view. While his poetic output changed as he grew older, this was once again a reflection of the outside world’s influence on his inner subjective experience. Witness his haunting ‘qita’a’ written while he was confined to Lahore’s Mayo hospital after a heart attack in 1982. He termed it ‘the experience of a sleepless night’ (‘ek bekhwaab raat ki waardaat’):

‘Iss waqt tau yuN lagta hai k ab kuch bhi nahiN hai

Mahtaab, na suraj, na andhera, na savera

AankhoN k dareechoN pe kisi husn ki chilman

Aur dil ki panaahoN maiN kisi dard ka dera’

Despite the melancholy evident in poems from his later life, Faiz remained staunch about the necessity of an artist to be socially committed “It is my firm conviction that poetry can be used for this purpose (of propagating a particular ideology), and that poetry is used for this purpose. The thing is that every word which we utter in our ordinary everyday language communicates some idea, some thought, some opinion to others, which influences them to some extent (and) if you bring about even a minute change in someone’s mind... then you have brought a change in the system of the world to that extent. Poetry can do this work to a great extent... a person need not employ slogans, shouts and direct political statements as poetry.” (Guftagoo—Faiz Ahmed Faiz. Scheherzade publications).

‘Writers, Where Do You Stand?’

Faiz was never apologetic about being socially and politically committed because that’s what he believed every artist should be. In his essay ‘Writers, Where Do You Stand?’, he clearly enunciated the role of a writer in society “He (or she) is committed to his country and his people. As a guide, philosopher and friend, he must lead them out of the darkness of ignorance, superstition and unreasoned prejudices into the light of knowledge and reason, out of the labyrinth of tyranny into the ways of freedom...” (Faiz: Culture and Identity).

And to those who would keep Art as a plaything of the rich or a commodity to be sold to the highest bidder, Faiz would have said that Art is neither master nor slave but humankind’s most profound guide. Of course Art is the voice and conscience of the artist but it is also the deepest expression of a collective voice, the voice of all people, throughout history. In its most radiant form, art shatters illusions, destroys prejudices and nurtures the highest ideals. This is the purpose of all art and all artists but especially those who are striving to free their fellow human beings from centuries of bondage.

Ali Madeeh Hashmi is a Psychiatrist and a trustee of the Faiz Foundation Trust. He can be reached at ahashmi39@gmail.com and on twitter @Ali_Madeeh.

February 13 was Faiz Ahmed Faiz’ 103rd birthday