In my last article in this paper (‘America’s forgotten war’ on June 30), I had suggested that there is an imperative need to revise our policy on Afghanistan and find common ground with the new American administration. The thrust of the article was that this was a self-evident requirement and needed no buttressing with a repetition of arguments and facts on the need to keep our relations with the US on an even keel.

It seems, however, that this is not the view our decision-makers espouse, as is evidenced by recent policy statements. “Pakistan continues to work for peace and progress in Afghanistan… and will continue to strive for [the] return of normalcy in Afghanistan at the earliest,” the National Security Council said in a statement after its latest meeting on Friday, July 7. But it went on to say: “This, however, requires simultaneous efforts by the Afghan government [to] restor[e] effective control [in] its territory.” These words are consistent with an earlier assertion by the NSC that “while counterterrorism efforts by Pakistan continue, it is time now for the other stakeholders, particularly Afghanistan to ‘do more’”. There was, it would seem, no mention of the agreement reached by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif with President Ashraf Ghani on the resurrection of the Quadrilateral Coordination Group (QCG) or about the agreement to exchange verifiable information on terrorists that each side wants the other to apprehend and hand over.

There is, it seems, a degree of confidence that Pakistan can sustain whatever measures the Mattis/ Tillerson/Masterson combine in the US decides to take as part of its approach for the region. These measures, it can be argued, cannot be too stringent, given the American interest in using Pakistan’s territory to supply its reinforced troop presence in Afghanistan, in encouraging the continuance of Pakistan’s anti-terrorism campaign, and the even larger interest of not destabilising the fragile Pakistan economy. After all, US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has acknowledged that there are numerous facets to the US-Pakistan relationship other than Afghanistan and they will obviously weigh heavily when they draw up their policy. We therefore have a rational basis for assuming that the Trump Administration will tread lightly. While this may well be true, many observers, including myself, would deem this position as overly optimistic given the recent statements made by such American political heavyweights as Senator John McCain and his colleagues, who in Pakistan praised our counterterrorism efforts—but when on Afghan soil emphasised that there would be consequences if Pakistan’s policy did not change materially.

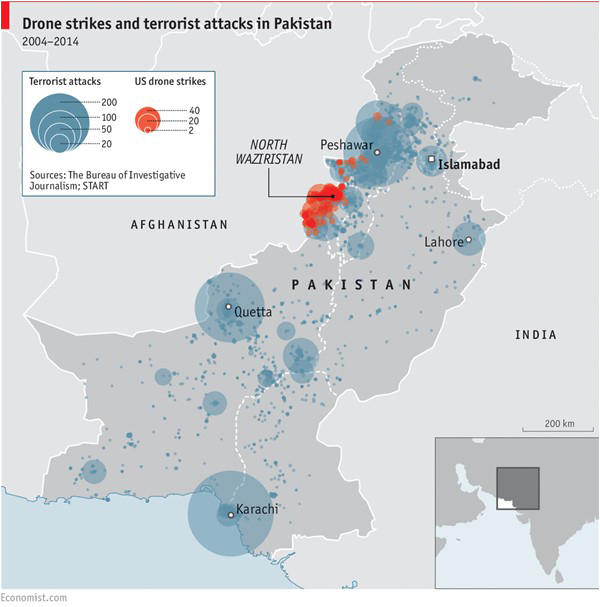

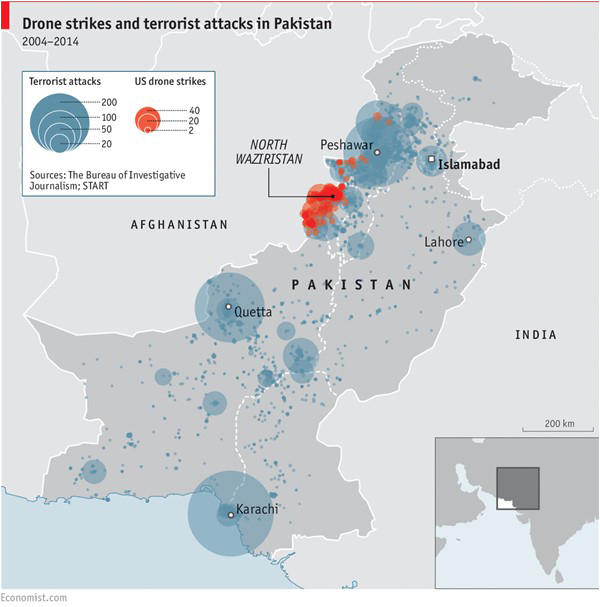

I would suggest, however, that the consequences for US-Pakistan relations, while extremely important, should carry less weight in our rational analysis of what a tolerance for the alleged presence of the Haqqani network and the Taliban leadership in Pakistan means for our internal situation. For many years now our decision-makers, both military and civil, have said that the principal threat to our security is internal and not external. We have rendered enormous sacrifices in the course of the numerous military campaigns to try to eliminate this threat. Most observers are agreed that this threat, while diminished, still persists. Observers also agree that our adversaries have and will continue to aid those elements in our body politic (the internal threat). We have every right to demand that Afghanistan do more to prevent the use of its soil for activities against us. But perhaps this may require a measure of reciprocity.

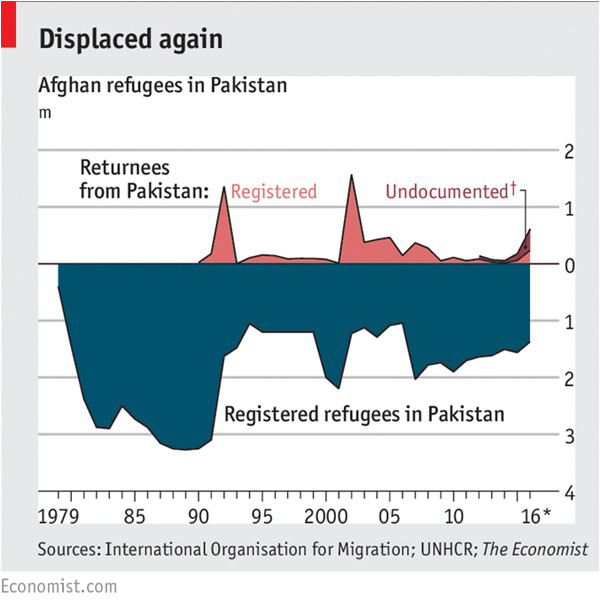

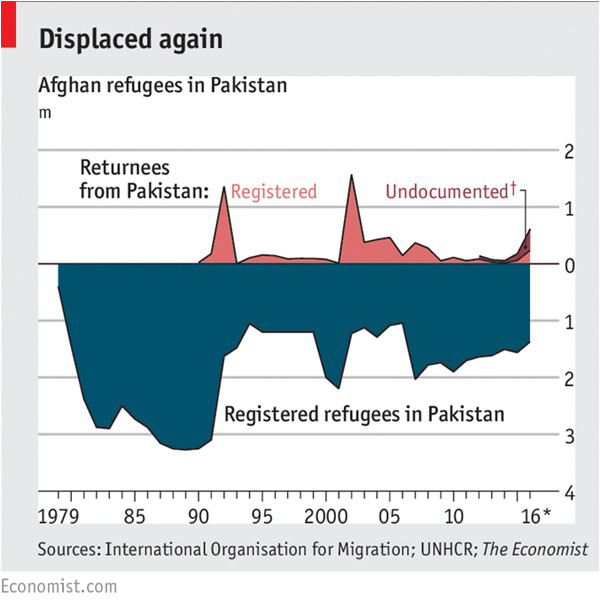

We want peace and stability in Afghanistan. This is driven, in part, by our sympathy for our Afghan brethren but largely by the recognition that instability in Afghanistan contributes to instability in Pakistan. The undoubted deterioration in the law and order situation throughout Pakistan is owed, at least in part—many would say in large part—to the presence of Afghan refugees on our soil. I believe they number about 5 million (1.7 million registered, 1.7 million unregistered, another 1.7 million with fraudulently acquired National Identity Cards or passports). Most of them are genuine refugees and deserve our sympathy.

But in putting “Pakistan First”, we have, after many years of patience, started with the process of sending them back. While this process will continue, it will be many years before it can be completed. At the same time, we have started the process of fencing our border with Afghanistan and taking other measures to ensure that movement across the Pak-Afghan border is governed by the same procedures that obtain between two sovereign independent countries. Again, it will be many years before this project can be completed.

Let us acknowledge that our efforts to send the Afghan refugees back to their country of origin is driven perhaps in part by the recognition that our economy can no longer sustain them at a time when our own unemployment figures are high. This economic factor is, however, less important than the danger they are perceived to be posing to our internal security and to the maintenance of law and order.

There is the perception, for example, (and perceptions can become important determinants of policy) that the Afghan presence, both of refugees and insurgent Taliban, has made it difficult to maintain law and order in cities such as Chaman and in such Quetta neighbourhoods such as Pushtunabad and Kharotabad.

There is the reality that the influx of Afghan refugees into Kurram Agency, changed the sectarian balance in that beleaguered area and created circumstances for strife, nay major battles, that its residents have had to face over the years. More recently, the perception has grown that insurgent Taliban and more importantly their Haqqani network partners have acquired an inordinately heavy role in the politics of the Agency, something that, in the eyes of many, was highlighted by the recent carnage.

There is the perception that as the crackdown on banned outfits continues in Karachi and elsewhere, many of those apprehended are not only from the TTP sympathisers of the Afghan Taliban, but also from the Afghan Taliban.

There is evidence, provided by Afghan sources, that many Taliban leaders, hitherto resident in Pakistan, have moved into Afghanistan, some with their families, primarily into Helmand province. A rational analysis would suggest that even when we set aside the dangerous repercussions for our external relationships that an insurgent Afghan presence on our soil creates, reducing our internal dangers requires that we limit our tolerance of their presence on our soil. What we need, therefore, is the creation of conditions in which this process of moving them into Afghanistan can be accelerated.

Internal security

Given the circumstances described above, it is clear that for some time to come we will not be insulated from the effects of the instability that plagues Afghanistan, and which, notwithstanding Afghan claims to the contrary, have little to do with the machinations of external forces. But can we, in addressing our internal security problems also advance the prospect of some degree of stability in Afghanistan?

Our oft-stated desire has been to do what we can to bring peace to Afghanistan even when Afghanistan remains riven with internal fissures and Kabul abounds with figures who benefit from continued instability. Reconciliation between the Afghan administration and the Taliban/Haqqani combine is the most important contribution that can be made towards this goal. We say that we can only facilitate such a dialogue along with our Chinese and American friends in the QCG but cannot force the Taliban to the table.

What would happen if we sought to persuade the Taliban leaders and active fighters to move to Afghanistan? It is probable that once they can operate only from Afghan soil many of the groups into which the Taliban have been split will agree to negotiations with President Ashraf Ghani. Even if they don’t, this will then be an internal Afghan problem.

We must recognise that whether negotiations take place or not, Afghanistan will remain troubled. The Americans and their allies must accept that the planned enhancement of their military may prevent a Taliban takeover and even bring them to the negotiating table, but if they are desirous of preventing the creation of a terrorist safe haven in Afghanistan, they must engage over many years in the nation-building to which many of Trumps closest aides are averse.

In the meanwhile, we will have taken a major step towards restoring the writ of the state over all areas of Pakistan. Let there be no mistake. We have a long and difficult road to traverse before we can rid ourselves of the internal difficulties that have been created over the years. We will continue to be dependent on the armed forces to wage Radd ul Fassad-like campaigns alongside a refurbished civil administration to finally prevail and restore the Pakistan that our founders had visualised.

An argument has been offered is that the presence of the Taliban, as our allies in Afghanistan, will prevent India from using Afghan soil against us. That India is doing so now is undeniable? We have an adversarial relationship and these games will be played both against us and by us. Does a rational analysis suggest, however, that India needs Afghanistan desperately for this purpose? It has a long, relatively porous land border with us and a smuggler’s paradise along our coastline in Balochistan if it wants to infiltrate agents, finance local insurgents or use other means to foment unrest.

Does it need the Afghan National Security Force to create a two-front situation when India is, in conventional military terms, so preponderantly superior? This is not to suggest that our armed forces are not capable of defending our borders but merely to point out that this inordinate emphasis on the Indo-Afghan nexus is not a rational basis for policy when closely examined.

So how should we proceed? Perhaps the first step should be to convene the QCG and following the recommendations accepted therein ask the Taliban to see the virtue of moving towards reconciliation. Perhaps we should tell them that while the Afghan people are tired of the strife and insecurity, the American troop reinforcement will ensure that the Taliban cannot win on the battlefield and therefore the discontent of the Afghan people will increase if the war continues and produces no result other than added misery.

Perhaps we should stress that Pakistan does not view the Ashraf Ghani government as a puppet and tell them that they should accept the Ghani government’s offer to open a negotiating office in Afghanistan with guarantees of safety being provided by the QCG members. Perhaps we should suggest that along with the Chinese, Pakistan will seek to ensure that such talks are not in any way weighted against the Taliban. It can also be said perhaps that Taliban factions opposed to such talks would remain sidelined and would be treated as spoilers by all parties of the QCG.

Perhaps we should warn that the people of Pakistan are extremely concerned about the costs (growth of sectarianism, extremism and economic dislocation) imposed by the Afghan problem. They want the government to insulate Pakistan from the internal Afghan situation and free Pakistan of the insurgent Taliban presence. Pakistani authorities could no longer ignore this overwhelming public demand even if there were no sign of movement towards a settlement in Afghanistan. If the Taliban are convinced that all centres of power in Pakistan are united in this demand, there is, I believe, a good chance that they will see the light.

Admittedly, our government is now almost totally preoccupied with the Panama Papers issue and decision-making in these circumstances is difficult. Can we nevertheless entertain the hope that a National Security Council meeting and a Foreign Office briefing for the PM suggest that the military and civilian power centres are keenly aware of the importance of the issue. Going further, can they perhaps agree to consider the foregoing analysis and accept the recommended course of action?

The writer heads the Global and Regional Studies Centre at IoBM, a Karachi-based university. He is a former foreign secretary and has served as ambassador to the US and Iran. He lectures at NDU and has written extensively on Pakistan and international relations

It seems, however, that this is not the view our decision-makers espouse, as is evidenced by recent policy statements. “Pakistan continues to work for peace and progress in Afghanistan… and will continue to strive for [the] return of normalcy in Afghanistan at the earliest,” the National Security Council said in a statement after its latest meeting on Friday, July 7. But it went on to say: “This, however, requires simultaneous efforts by the Afghan government [to] restor[e] effective control [in] its territory.” These words are consistent with an earlier assertion by the NSC that “while counterterrorism efforts by Pakistan continue, it is time now for the other stakeholders, particularly Afghanistan to ‘do more’”. There was, it would seem, no mention of the agreement reached by Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif with President Ashraf Ghani on the resurrection of the Quadrilateral Coordination Group (QCG) or about the agreement to exchange verifiable information on terrorists that each side wants the other to apprehend and hand over.

A rational analysis would suggest that even when we set aside the dangerous repercussions for our external relationships that an insurgent Afghan presence on our soil creates, reducing our internal dangers requires that we limit our tolerance of their presence on our soil

There is, it seems, a degree of confidence that Pakistan can sustain whatever measures the Mattis/ Tillerson/Masterson combine in the US decides to take as part of its approach for the region. These measures, it can be argued, cannot be too stringent, given the American interest in using Pakistan’s territory to supply its reinforced troop presence in Afghanistan, in encouraging the continuance of Pakistan’s anti-terrorism campaign, and the even larger interest of not destabilising the fragile Pakistan economy. After all, US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has acknowledged that there are numerous facets to the US-Pakistan relationship other than Afghanistan and they will obviously weigh heavily when they draw up their policy. We therefore have a rational basis for assuming that the Trump Administration will tread lightly. While this may well be true, many observers, including myself, would deem this position as overly optimistic given the recent statements made by such American political heavyweights as Senator John McCain and his colleagues, who in Pakistan praised our counterterrorism efforts—but when on Afghan soil emphasised that there would be consequences if Pakistan’s policy did not change materially.

I would suggest, however, that the consequences for US-Pakistan relations, while extremely important, should carry less weight in our rational analysis of what a tolerance for the alleged presence of the Haqqani network and the Taliban leadership in Pakistan means for our internal situation. For many years now our decision-makers, both military and civil, have said that the principal threat to our security is internal and not external. We have rendered enormous sacrifices in the course of the numerous military campaigns to try to eliminate this threat. Most observers are agreed that this threat, while diminished, still persists. Observers also agree that our adversaries have and will continue to aid those elements in our body politic (the internal threat). We have every right to demand that Afghanistan do more to prevent the use of its soil for activities against us. But perhaps this may require a measure of reciprocity.

We want peace and stability in Afghanistan. This is driven, in part, by our sympathy for our Afghan brethren but largely by the recognition that instability in Afghanistan contributes to instability in Pakistan. The undoubted deterioration in the law and order situation throughout Pakistan is owed, at least in part—many would say in large part—to the presence of Afghan refugees on our soil. I believe they number about 5 million (1.7 million registered, 1.7 million unregistered, another 1.7 million with fraudulently acquired National Identity Cards or passports). Most of them are genuine refugees and deserve our sympathy.

But in putting “Pakistan First”, we have, after many years of patience, started with the process of sending them back. While this process will continue, it will be many years before it can be completed. At the same time, we have started the process of fencing our border with Afghanistan and taking other measures to ensure that movement across the Pak-Afghan border is governed by the same procedures that obtain between two sovereign independent countries. Again, it will be many years before this project can be completed.

Let us acknowledge that our efforts to send the Afghan refugees back to their country of origin is driven perhaps in part by the recognition that our economy can no longer sustain them at a time when our own unemployment figures are high. This economic factor is, however, less important than the danger they are perceived to be posing to our internal security and to the maintenance of law and order.

There is the perception, for example, (and perceptions can become important determinants of policy) that the Afghan presence, both of refugees and insurgent Taliban, has made it difficult to maintain law and order in cities such as Chaman and in such Quetta neighbourhoods such as Pushtunabad and Kharotabad.

There is the reality that the influx of Afghan refugees into Kurram Agency, changed the sectarian balance in that beleaguered area and created circumstances for strife, nay major battles, that its residents have had to face over the years. More recently, the perception has grown that insurgent Taliban and more importantly their Haqqani network partners have acquired an inordinately heavy role in the politics of the Agency, something that, in the eyes of many, was highlighted by the recent carnage.

There is the perception that as the crackdown on banned outfits continues in Karachi and elsewhere, many of those apprehended are not only from the TTP sympathisers of the Afghan Taliban, but also from the Afghan Taliban.

There is evidence, provided by Afghan sources, that many Taliban leaders, hitherto resident in Pakistan, have moved into Afghanistan, some with their families, primarily into Helmand province. A rational analysis would suggest that even when we set aside the dangerous repercussions for our external relationships that an insurgent Afghan presence on our soil creates, reducing our internal dangers requires that we limit our tolerance of their presence on our soil. What we need, therefore, is the creation of conditions in which this process of moving them into Afghanistan can be accelerated.

Internal security

Given the circumstances described above, it is clear that for some time to come we will not be insulated from the effects of the instability that plagues Afghanistan, and which, notwithstanding Afghan claims to the contrary, have little to do with the machinations of external forces. But can we, in addressing our internal security problems also advance the prospect of some degree of stability in Afghanistan?

Our oft-stated desire has been to do what we can to bring peace to Afghanistan even when Afghanistan remains riven with internal fissures and Kabul abounds with figures who benefit from continued instability. Reconciliation between the Afghan administration and the Taliban/Haqqani combine is the most important contribution that can be made towards this goal. We say that we can only facilitate such a dialogue along with our Chinese and American friends in the QCG but cannot force the Taliban to the table.

What would happen if we sought to persuade the Taliban leaders and active fighters to move to Afghanistan? It is probable that once they can operate only from Afghan soil many of the groups into which the Taliban have been split will agree to negotiations with President Ashraf Ghani. Even if they don’t, this will then be an internal Afghan problem.

We must recognise that whether negotiations take place or not, Afghanistan will remain troubled. The Americans and their allies must accept that the planned enhancement of their military may prevent a Taliban takeover and even bring them to the negotiating table, but if they are desirous of preventing the creation of a terrorist safe haven in Afghanistan, they must engage over many years in the nation-building to which many of Trumps closest aides are averse.

In the meanwhile, we will have taken a major step towards restoring the writ of the state over all areas of Pakistan. Let there be no mistake. We have a long and difficult road to traverse before we can rid ourselves of the internal difficulties that have been created over the years. We will continue to be dependent on the armed forces to wage Radd ul Fassad-like campaigns alongside a refurbished civil administration to finally prevail and restore the Pakistan that our founders had visualised.

An argument has been offered is that the presence of the Taliban, as our allies in Afghanistan, will prevent India from using Afghan soil against us. That India is doing so now is undeniable? We have an adversarial relationship and these games will be played both against us and by us. Does a rational analysis suggest, however, that India needs Afghanistan desperately for this purpose? It has a long, relatively porous land border with us and a smuggler’s paradise along our coastline in Balochistan if it wants to infiltrate agents, finance local insurgents or use other means to foment unrest.

Does it need the Afghan National Security Force to create a two-front situation when India is, in conventional military terms, so preponderantly superior? This is not to suggest that our armed forces are not capable of defending our borders but merely to point out that this inordinate emphasis on the Indo-Afghan nexus is not a rational basis for policy when closely examined.

So how should we proceed? Perhaps the first step should be to convene the QCG and following the recommendations accepted therein ask the Taliban to see the virtue of moving towards reconciliation. Perhaps we should tell them that while the Afghan people are tired of the strife and insecurity, the American troop reinforcement will ensure that the Taliban cannot win on the battlefield and therefore the discontent of the Afghan people will increase if the war continues and produces no result other than added misery.

Perhaps we should stress that Pakistan does not view the Ashraf Ghani government as a puppet and tell them that they should accept the Ghani government’s offer to open a negotiating office in Afghanistan with guarantees of safety being provided by the QCG members. Perhaps we should suggest that along with the Chinese, Pakistan will seek to ensure that such talks are not in any way weighted against the Taliban. It can also be said perhaps that Taliban factions opposed to such talks would remain sidelined and would be treated as spoilers by all parties of the QCG.

Perhaps we should warn that the people of Pakistan are extremely concerned about the costs (growth of sectarianism, extremism and economic dislocation) imposed by the Afghan problem. They want the government to insulate Pakistan from the internal Afghan situation and free Pakistan of the insurgent Taliban presence. Pakistani authorities could no longer ignore this overwhelming public demand even if there were no sign of movement towards a settlement in Afghanistan. If the Taliban are convinced that all centres of power in Pakistan are united in this demand, there is, I believe, a good chance that they will see the light.

Admittedly, our government is now almost totally preoccupied with the Panama Papers issue and decision-making in these circumstances is difficult. Can we nevertheless entertain the hope that a National Security Council meeting and a Foreign Office briefing for the PM suggest that the military and civilian power centres are keenly aware of the importance of the issue. Going further, can they perhaps agree to consider the foregoing analysis and accept the recommended course of action?

The writer heads the Global and Regional Studies Centre at IoBM, a Karachi-based university. He is a former foreign secretary and has served as ambassador to the US and Iran. He lectures at NDU and has written extensively on Pakistan and international relations