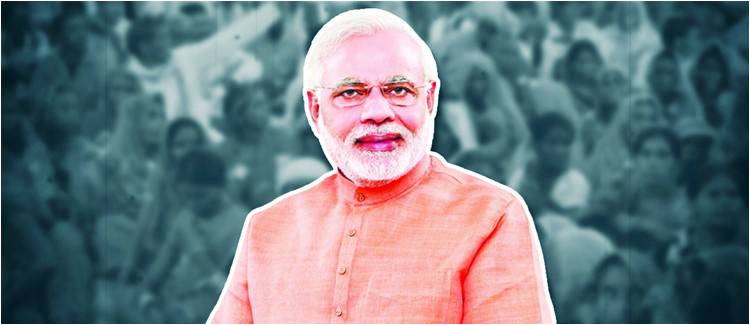

It is not surprising that Narendra Modi has bagged majority of votes and become India’s premier for a second term. His aggressive policies and isolationist policies with respect to Pakistan are known to all. How will Pakistan be moved by this outcome? I believe one must take a deeper look at Modi’s belligerent policies vis a vis Pakistan to answer this question.

Military strategist and theorist Carl Von Clausewitz elaborated on the psychological and political aspects of war and how it can be used “as an instrument of policy.” Can the warmongering during the Pulwama attack in February be seen as a thoroughly calculated and premeditated strategy?

Clausewitz in his magnum opus On War labelled war as the “continuation of politics by other means” but despite the two World Wars humanity has faced, the definition not been altered in any meaningful way.

Seen through an analytical lens, the sabre-rattling circumstances that India shaped after the Pulwama attack appeared to be more like the continuation of party politics steered by the objectives of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to engineer a favourable political environment for triumph in the elections.

To embark on any kind of war, there needs a root cause or intention to attain a political objective. Post-Pulwama, warfare was politicised by the Modi government and the Indian military engagement appeared not as an outcome of a political goal, but rather a monocratic politician’s agenda.

Clausewitz’s theory also insinuates that any war which is to be waged in the future must also end after it has achieved its political ends. The question then arises: will there be a change in PM Modi’s goals, interests, decisions and his political nature?

There is no doubt that many politicians have been unable to resist their impulses when the opportunity for war presented itself. Still, wars are seen as policy failures - like the Balkan Wars, the Vietnam War and the War in Iraq. Nevertheless, power-hungry politicians were rewarded domestically and strategically.

Lyndon Johnson, the 36th president of the United States from the Democratic Party, is one such example. He prolonged the Vietnam War and got re-elected as president. Tony Blair - the leader of the Labour party who led Britain to the debacle in the Iraq War - stayed the longest in office in comparison to any other Labour leader in the history of Britain.

In the 21st century, Clausewitz’s policy objectives do not always direct reasons for war. Every state’s domestic politics determines its objectives for war. Rupert Smith, in his book The Utility of Force, writes that power politics is deployed to circumvent risks at home, rather than resolving the purpose for waging war. France followed India’s footsteps and subsequently, France intensified its strikes on ISIS in Syria and Iraq after terrorist attacks in Paris, which drove many political analysts to infer that those attacks were not focused to obliterate ISIS but were purely for domestic consumption.

There is also another tendency of politicians who show a preference for wars to emphasise a ‘committed nation.’ The commitment shown from any nation is a continuous process which is achieved and empowered through the fourth pillar of the state; the media that guides and leads the war frenzy to be sold to consumer citizens’ who are satisfied with the notion of distance fighting.

Other than the unsuccessful airstrikes by India this year in Pakistan’s territory, the intervention in Libya of 2011 is another classic example. The US and Britain shot more than 100 Tomahawk Cruise Missiles in Libya. The coalition forces, led by US, approved many drone air strikes without any troops on land. These global powers ruined the state of Libya as they continue to suffer civil war. This facilitated world powers to effortlessly pull out forces from the region. The past wars of US in Afghanistan and Iraq were also an effort to discipline and exploit people overseas to win wars at home. Undoubtedly this was the method that PM Modi applied in 2019 to his own political party’s benefit.

Pakistan’s premier Imran Khan was of the opinion the two South Asian neighbours now had the possibility of a better understanding under the right-wing Modi government, compared to a Congress government. PM Modi should not have any doubts about PM Imran Khan’s obligation towards harmony and prosperity and the latter can only hope that Modi will abstain from his populist political rhetoric while referring to Pakistan.

One man’s military operation (French invasion of Russia) is another man’s nationalistic war. The conditions of Russia were created to overpower the biggest army ever mustered in the history of wars until that period. Engaging in long drawn out wars and fighting on several fronts are issues that Modi himself opened up in his first term. Challenging Modi’s objectives will be difficult but it must be done. His return to power should be seen as a fresh opportunity to rekindle friendship between Pakistan and India. The time has arrived for PM Modi to re-evaluate his thoughts and sentiments.

Military strategist and theorist Carl Von Clausewitz elaborated on the psychological and political aspects of war and how it can be used “as an instrument of policy.” Can the warmongering during the Pulwama attack in February be seen as a thoroughly calculated and premeditated strategy?

Clausewitz in his magnum opus On War labelled war as the “continuation of politics by other means” but despite the two World Wars humanity has faced, the definition not been altered in any meaningful way.

Seen through an analytical lens, the sabre-rattling circumstances that India shaped after the Pulwama attack appeared to be more like the continuation of party politics steered by the objectives of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to engineer a favourable political environment for triumph in the elections.

There is no doubt that many politicians have been unable to resist their impulses when the opportunity for war presented itself. Still, wars are seen as policy failures

To embark on any kind of war, there needs a root cause or intention to attain a political objective. Post-Pulwama, warfare was politicised by the Modi government and the Indian military engagement appeared not as an outcome of a political goal, but rather a monocratic politician’s agenda.

Clausewitz’s theory also insinuates that any war which is to be waged in the future must also end after it has achieved its political ends. The question then arises: will there be a change in PM Modi’s goals, interests, decisions and his political nature?

There is no doubt that many politicians have been unable to resist their impulses when the opportunity for war presented itself. Still, wars are seen as policy failures - like the Balkan Wars, the Vietnam War and the War in Iraq. Nevertheless, power-hungry politicians were rewarded domestically and strategically.

Lyndon Johnson, the 36th president of the United States from the Democratic Party, is one such example. He prolonged the Vietnam War and got re-elected as president. Tony Blair - the leader of the Labour party who led Britain to the debacle in the Iraq War - stayed the longest in office in comparison to any other Labour leader in the history of Britain.

In the 21st century, Clausewitz’s policy objectives do not always direct reasons for war. Every state’s domestic politics determines its objectives for war. Rupert Smith, in his book The Utility of Force, writes that power politics is deployed to circumvent risks at home, rather than resolving the purpose for waging war. France followed India’s footsteps and subsequently, France intensified its strikes on ISIS in Syria and Iraq after terrorist attacks in Paris, which drove many political analysts to infer that those attacks were not focused to obliterate ISIS but were purely for domestic consumption.

There is also another tendency of politicians who show a preference for wars to emphasise a ‘committed nation.’ The commitment shown from any nation is a continuous process which is achieved and empowered through the fourth pillar of the state; the media that guides and leads the war frenzy to be sold to consumer citizens’ who are satisfied with the notion of distance fighting.

Other than the unsuccessful airstrikes by India this year in Pakistan’s territory, the intervention in Libya of 2011 is another classic example. The US and Britain shot more than 100 Tomahawk Cruise Missiles in Libya. The coalition forces, led by US, approved many drone air strikes without any troops on land. These global powers ruined the state of Libya as they continue to suffer civil war. This facilitated world powers to effortlessly pull out forces from the region. The past wars of US in Afghanistan and Iraq were also an effort to discipline and exploit people overseas to win wars at home. Undoubtedly this was the method that PM Modi applied in 2019 to his own political party’s benefit.

Pakistan’s premier Imran Khan was of the opinion the two South Asian neighbours now had the possibility of a better understanding under the right-wing Modi government, compared to a Congress government. PM Modi should not have any doubts about PM Imran Khan’s obligation towards harmony and prosperity and the latter can only hope that Modi will abstain from his populist political rhetoric while referring to Pakistan.

One man’s military operation (French invasion of Russia) is another man’s nationalistic war. The conditions of Russia were created to overpower the biggest army ever mustered in the history of wars until that period. Engaging in long drawn out wars and fighting on several fronts are issues that Modi himself opened up in his first term. Challenging Modi’s objectives will be difficult but it must be done. His return to power should be seen as a fresh opportunity to rekindle friendship between Pakistan and India. The time has arrived for PM Modi to re-evaluate his thoughts and sentiments.