In the early days of April this year, an exhibition titled “Elegance of Script” was organized by the Lahore Museum, in which the calligraphic works in Nastaliq, Thuluth, Naskh and other Arabic and Persian scripts by different master calligraphers from Pakistan and pre-partition India were exhibited. Curated by Ms Iffat Azeem, the Keeper of the Manuscript Gallery, and inaugurated by Mr Durmus Bastug, Counsel General Turkiye in Lahore, it aimed towards exploring the contribution of Lahori calligraphers in this field through their artworks and to study the development of the different scripts. Spread over three galleries, the exhibition displayed the artworks of more than a dozen calligraphers. The most dominantly visible script among the artworks was Nastaliq, in which majority of the calligraphy in Urdu language has been executed in both India and Pakistan; while for the purpose of quickly writing in Nastaliq script, a streamlined form called Shekastah had been devised.

In India and Pakistan, a lot of changes have been brought into Nastaliq, and the city of Lahore has been considered an important city, where considerable efforts have been made in this regard. All those efforts led to the establishment of a whole new school of the said calligraphic script.

Nastaliq is one of the many major calligraphic hands used to write in Arabic, Persian, Kashmiri, Shahmukhi Punjabi and Urdu languages. It is popularly known to have been invented by combining two earlier scripts called Naskh and Ta’aliq, thus the word Nastaliq. While according to the art historian Sheila Blair, the word Nastaliq is a contraction of the word “Naskh-i-taliq” which means hanging or suspended Naskh. If one looks closely and compares the two scripts i.e. Naskh and Nastaliq, one can easily notice that the shape of characters in Naskh script have been made in a way that they appear to be slightly swinging from the top right to the lower left side of each word in the Nastaliq script. It appears as if they are suspended from an imaginary line. It is an elegant cursive script that features exaggerated rounded forms and elongated horizontal strokes.

Majority of the scholars attribute the invention of Nastaliq script to the 14th-century Persian calligrapher Mir Ali Tabrizi, but Elaine Wright found out that some Shirazi scribes began modifying and experimenting with the Naskh script, and Mir Ali Tabrizi brought final perfection to the modified script. Scholars tell us that the process began in the 11th century and reached its perfection in the 15th century.

The first master calligrapher of this script was undoubtedly Mir Ali Tabrizi. Later on, it was practiced and promoted in the courts of various sultans by a lineage of subsequent calligraphers, particularly in the courts of Safavid and Timurid sultans.

The Timurids brought Nastaliq to Indian subcontinent where it became the favourite script at the court of Mughal rulers. The notable calligraphers of Nastaliq include Jafar Tabrizi, Sultan Ali Mashhadi, Mir Emad Hassani, Mir Ali Heravi, Abdur Rasheed Delmi and others.

Aside from the court of the Mughal kings, various individual schools of Nastaliq had been established in Lahore, Kashmir, Delhi, Hyderabad Deccan, and Calcutta, where the masters of this art brought variations in the script. Because of those variations accredited to those different schools, the calligraphic works produced by them can easily be distinguished from one another. According to Anis Chishti, soon the calligraphy schools of Lahore and Delhi became the two main centres for Nastaliq calligraphy.

The circular-shaped letters such as yay, jeem, sin and qaf in ‘Lahori Nastaliq’ have elliptical character to them, while those in ‘Delhi Nastaliq’ are completely round. The same case is with the letters in Lucknow, Kashmir, Calcutta and Hyderabad Deccan schools. Apart from the variations in the rules of different calligraphy schools, differences exist in the artistic renderings among the works of disciples from the same school.

With regards to the Lahore School of Calligraphy, the pioneering figure is Imam Verdi (1790-1880), who migrated to Lahore from Kabul at a young age, and is considered the last master of Iranian Nastaliq in Lahore. Many years later, the ‘Lahore School of Nastaliq’ emerged in 1928 with the arrival of Khalifa Abdul Majeed Parveen Raqam (1901-1946) and the exhibition in question at the Lahore Museum begins with the display of works made by him. According to Sehar A. Shah, responding to some technical issues with the Iranian Nastaliq, Abdul Majeed modified the script to create the Lahori style.

The Iranian Nastaliq was inherently a delicate script and did not work out very well with the printing process, as the finely penned lines tend to fade in print. Consequently, the Lahori style with vertical letters and bold joints was brought out by Khalifa Abdul Majeed in collaboration with a scholarly figure Hakim Faqir Muhammad Chishti, who provided valuable advice, critiques and encouragement in the process of developing this style.

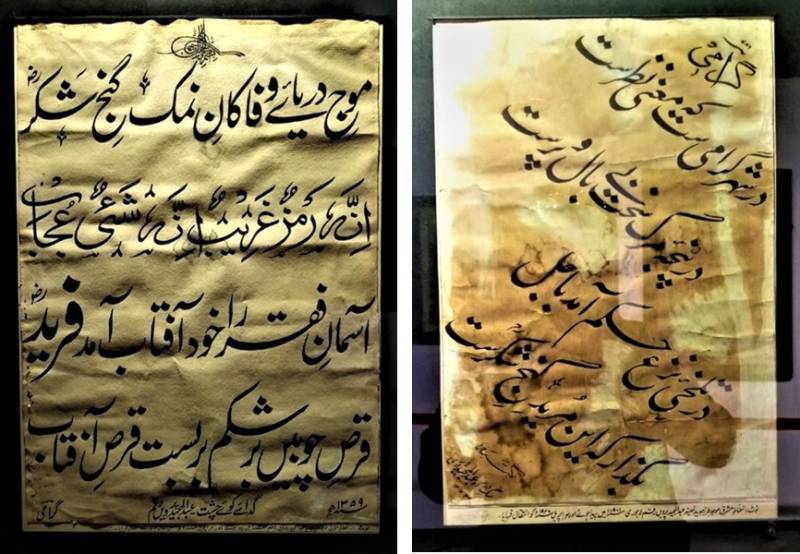

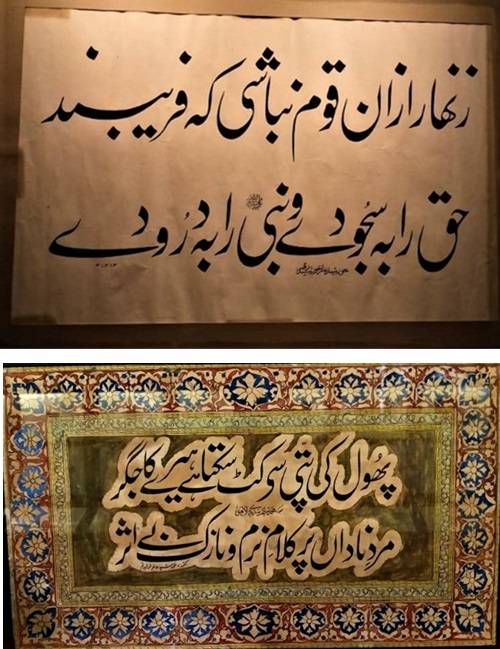

The artistic works by Khalifa Abdul Majeed Parveen exhibited in this exhibition are mostly Persian verses beautifully scribed in black ink, that typically articulate the calligraphic style consisting of bold shapes, deep curvature of letters, and pointed ends with refined shaping. It was Maulana Ghulam Rasul Mehr, a famous scholar and supporter of the Pakistan movement, who conferred the title “Parveen Raqam” to Khalifa Abdul Majeed, the poetic meaning of which is “one whose pen radiates moonlight.”

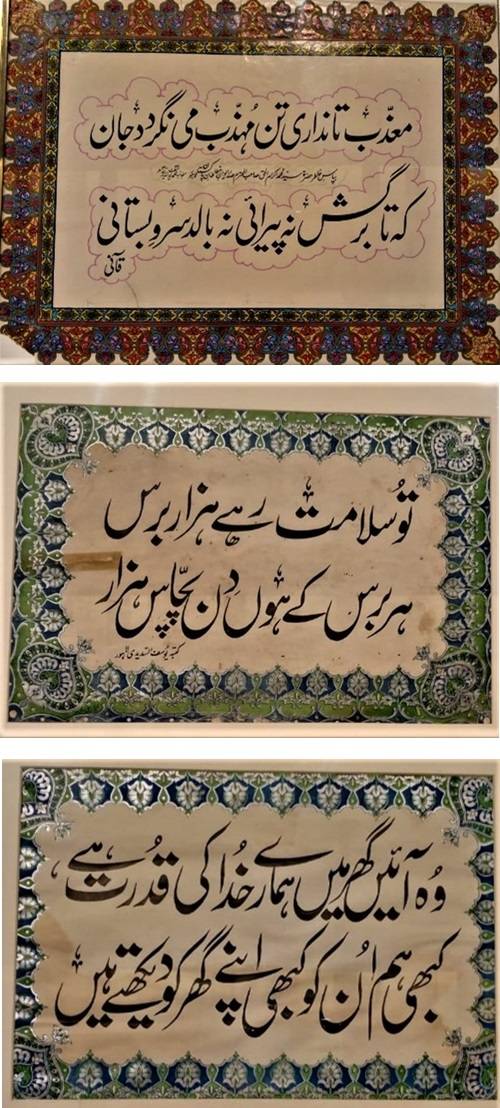

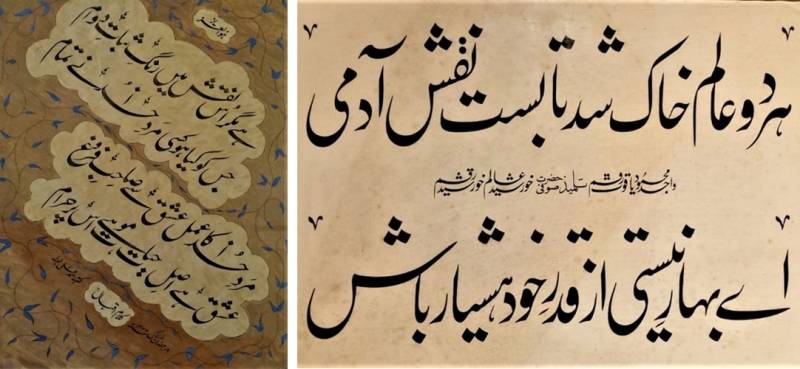

Along with Abdul Majeed Parveen Raqam, Tajuddin Zareen Raqam and Muhammad Siddique Almas Raqam were the two initial key figures of the Lahore School of Nastaliq. Zareen Raqam (1906-1955) was a contemporary of Khalifa Abdul Majeed, and trained himself with copying and practicing of the original calligraphic compositions by the latter. Through this imitation of Parveen Raqam’s works, Zareen Raqam himself became the master of the skill and later trained a huge number of students in learning this script including Hafiz Yusuf Sadidi and Sufi Khursheed Alam Khursheed, who he taught at his academy at Lahore’s Baithak-e-Kaatibaan (Calligraphers’ Room). He also had published a book Muraqqa-i-Zareen on Lahori Nastaliq for codifying the script, and it acted as a guide for students of calligraphy. At the museum’s exhibition, his calligraphic renditions of a number of Quranic verses and other Urdu and Persian poetic verses, bordered by beautiful floral designs, are displayed.

After Zareen Raqam, the reins of the Lahore School were held by his students and later on a lineage of their subsequent students. The three famous students of Zareen Raqam were: Hafiz Yusuf Sadidi, Sufi Khursheed Alam and Anwar Hussain Nafees Raqam. In the post-partition era, Hafiz Yusuf Sadidi (1928-1986) became the most famous calligrapher of this school.

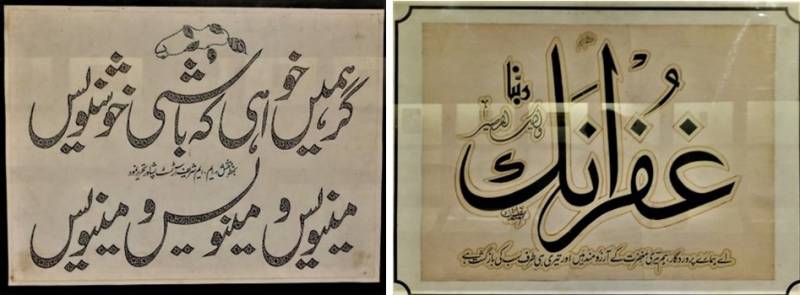

Born in Chakwal, he had visited Lahore, Peshawar and Delhi to perfect his skill in Naskh, Thuluth, Diwani, Riqa, Kufic and Nastaliq scripts. Due to mastery over the subject, he had been commissioned to write calligraphy for a number of architectural projects, including Mizaar-e-Iqbal, Jamia Ashrafia and the Tomb of Qutbuddin Aibak. He was the Chief Katib of the Daily Imroz. His calligraphic works outnumbering all others at the museum’s exhibition conveys his importance.

Another notable calligrapher of Lahore School was Sufi Khursheed Alam Khursheed Raqam (1927-2004). Born in the princely state of Kapurthala, he later on migrated to Lahore and became a disciple of Tajuddin Zareen Raqam. Eventually he became proficient in Nastaliq and later on the Khalifa (deputy) of his teacher. After the death of the latter, Sufi Khursheed was chosen as the custodian of Tajuddin Zareen’s Academy. He was a Sufi and Dervish, and was quite popular among his students that numbered in hundreds. Also, he was a chief scribe in a number of newspapers.

A lesser-known calligrapher of Lahore school was M. M. Ashraf Artist from Peshawar, who had been a disciple of Zareen Raqam. He was also a teacher of Hafiz Yusuf Sadeedi and is known as founder of ‘Peshawar School of Calligraphy’. He had invented ‘Abri Script’ and brought several innovations to calligraphic scripts.

Another prominent calligrapher of Lahore School was Syed Anwar Hussain Nafees Raqam (1933-2009). Born into a family of calligraphers in Sialkot, he had learned calligraphy from his father. Beginning his career in the Ehsan Newspaper, he had later served as the chief calligrapher in daily Nawa-i-Waqt. He had students belonging to different nationalities, including Afghanistan, Myanmar and Bangladesh. He would usually train his students with more than one scripts, and besides that they were also trained in spirituality. His masterpieces can be witnessed at Allama Iqbal Museum, Masjid Salah al Din (Timber Market), Masjid Hazrat Ali Chowk, Masjid Faiz Al Islam etc. At the museum exhibition, none of his Nastaliq specimens are exhibited, but one in Thuluth script is displayed.

After the above-mentioned calligraphers, their students subsequently took it upon themselves to promote the Lahore School of Nastaliq, and are still actively working on it to teach it to the next generation. These calligraphers include, Hafiz Bahar-i-Mustafa Sadidi (son of Hafiz Yusuf Sadidi), Ikram Ul Haq, Ahmed Ali Bhutta, Wajid Yaqoot, Khalid Javed Yusufi and others. Their works are also exhibited in the museum exhibition.

Upon being asked about the aims and aspirations behind organizing this wonderful exhibition, Ms Iffat Azeem, the keeper of Manuscripts Gallery, told the author that the main aim behind this exhibition was to make the general public and the students of art and history aware of our country’s heritage linked with calligraphy and the services rendered by our calligraphers in establishing and promoting this art.

For this purpose, a good number of artifacts, kept in Lahore Museum’s storage vault, were used for this exhibition alongside the artworks lent by collectors and practicing artists. She also aspires to establish a calligraphy gallery inside the Lahore Museum that will permanently exhibit these calligraphic masterpieces in it. All in all, this exhibition presented carefully curated masterpieces, that together with the meticulously researched descriptions give useful insights to the visitors about the subject.

Though the exhibition presented the artworks in various different calligraphic scripts, but the author was fortunate enough to find the evolution of Lahori Nastaliq through the works of the above-mentioned calligraphers in the exhibition. Such exhibition helps an inquisitive visitor to know what the handwritten script by the calligraphers and scribes working at different Urdu newspapers looked like, before the advent of digitally generated Urdu scripts. One must say that this exhibition shares the opportunity with today’s artists, historians and graphic designers to learn a lot from our past. Such exhibitions should be held off and on.