In a recent interview, his hair perfectly coiffed and dyed black, he looked harassed and bewildered, yet arrogant and devoid of self-awareness all at the same time. He said he wouldn’t want his sons overseas to come visit him in Lahore now because it is too dangerous. And I thought about the kid in Lahore who did himself so much harm by rioting because his leader told him that it was better to die than to be enslaved. But I want to plea for mercy for the kid, because while he did steal, he, in effect saved a peacock from harm, possibly from being roasted. He’s been labeled ‘Mor Commodore.’

But what about the peacock who can’t be saved from himself. How is he so unable to read the writing on the wall, or read a room, or even know that his words don’t add up? He seems almost naïve or innocent in his obstinate narration of his fact free version of history, which changes from hour to hour, and his right to be right.

I have a small but telling anecdote to share about this particular project, the political peacock-hero. It is from decades ago but remains relevant. Not much has changed it seems. The anecdote begins when my dear family friends, a husband wife duo – both of them Pakistan educated doctors, invited me over for the weekend. They were the sweetest, kindest and most generous couple, totally devoted to all things Pakistan.

How is he so unable to read the writing on the wall, or read a room, or even know that his words don’t add up? He seems almost naïve or innocent in his obstinate narration of his fact free version of history, which changes from hour to hour, and his right to be right.

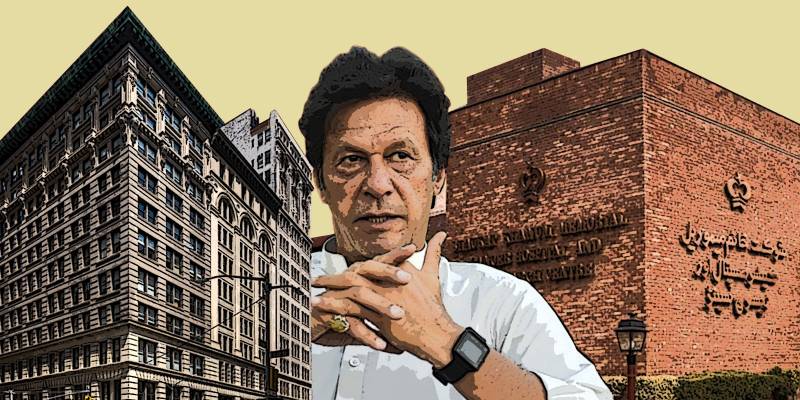

The peacock-hero was coming over from abroad to consult with them and other Pakistani doctors on setting up a hospital in Lahore. This was the summer of 1989. And this was probably the start of our hero’s invaluable interactions for himself with the professional and prosperous Pakistani American diaspora, who far away from their motherland, found an opportunity to feel connected through his glittering feathers and superhero aura. They probably recognized that he had the potential to convene people for charitable public good.

Uncle had organized a gathering of doctors of Pakistani descent in North America at his home to meet our hero for this purpose of doing great things for their own motherland. Our hero was going to stay with Uncle and his family for the weekend.

Uncle asked if I wanted to come too. I said yes. Of course! So he picked me from the city in his Jaguar and we drove to JFK to pick up our hero and then off we went to Uncle’s home. Our hero sat in front and I sat in the back seat. His blue blazer was placed on the seat next to me in the back (I considered that an honor in and of itself) and his valise was in the trunk.

On the two hour drive, our hero talked about his mother and how she had died of a misdiagnosis of a malignant tumor as something harmless. He blamed the doctor, his cousin, for negligence. The cousin had conducted x-rays instead of an MRI and CT scan, our hero told Uncle. Our hero was in anguish about this. If only he had known - if only he could’ve gotten his mother the care she needed in time, she would have lived. It was truly heart wrenching to listen to him express his regret and to want to set it right through a hospital.

It was clear that this was the motivation for the hospital and that our hero was deeply wounded by the death of his beloved mother. He credited his mother with his siblings’ education and successes. She had sold her own wedding gold jewelry, he told Uncle, so that he could be educated. His mother was his hero. I sat in the back seat listening in deep sympathy, contemplating the journey of our hero.

The peacock hero mentioned how a couple of years ago, doctors had gotten his own leg fracture wrong. They had done an x-ray and found nothing and treated it like an inflamed tendon. Finally, a CT scan had showed a barely visible hairline fracture.

We arrived at Uncle’s beautiful sprawling mansion, nestled in the woods. There was an indoor swimming pool and acres of land and woods. And yet it seemed so understated. He had prepared a lavish dinner, which he had cooked himself. There were at least 50 doctors there that evening. All of them were of Pakistani origin.

The evening went off well—all the guests, men and women were mostly couples and most of them were doctors. They were fans, and fawned over our hero. He had put on his blue blazer over a white shirt and khaki trousers. They gathered around him adoringly; they all were so proud of him. They felt honored to be in his presence and told him as much. He was their hero. And more so now because he was going to set up a hospital and was giving them an opportunity to be useful to him. They all pledged their unwavering support for his vision, and promised to help raise funds for him, work voluntarily and guide him.

Everyone in the room was successful and influential amongst the Pakistani diaspora and in their own communities where they practiced. Most were apolitical, involved in non-governmental charities, interested in things getting done back home, the trains running on time, and had a deep sense of nostalgia and homeland pride. Here before them stood their chance to graft their favorite game and its hero with their medical expertise. What could possibly be wrong with that?

Early at dawn—I slipped out of my room to walk outside in the huge garden—I was barefooted and the dew on the moist grass was summer telegraphing its magic to me through my soles. I was wearing a mid-calf length khaki thick cotton skirt and a white shirt. My favorite, bought at Zainab market—the reject defected factory goods for a Banana Republic order. It was my best look.

As I strolled around the periphery of the garden where the woods began, I said a silent prayer of thanks for not having mentioned anything about the political situation in Pakistan or Bhutto or Benazir or Zia the entire evening. I had shared one of the guest rooms with another woman who was visiting Uncle and Auntie. Later at night, while sharing our stories from back home, I found out that my roommate was the daughter of one of the Generals that had been blown up with Zia in his plane the year before in August 1988.

And of course I was full of anticipation for my big moment of gift giving and then about having the boasting rights to be able to tell friends back home that I had technically spent a weekend with our hero!

I have immense respect, empathy and care for the millions of people who adore my hero-no-more. Because he is their first love ever as a primo supremo. They’ve had decades of a relentless sense of collective victimhood and humiliation.

My gift for our peacock hero were photos I had taken myself in Karachi of a boy without shoes in a black shalwar kameez on a Friday afternoon playing cricket, feeling his joy, feeling his power. This had inspired a whole chapter in my novel Mass Transit. In that scene, Ameneh sits out on the mosaic tile terrace of her family home early morning before dawn in Karachi and recites Sura-e-Qadr over and over again while keeping count on a new fangled palm held counter shaped like a golf ball with changing digits each time it was pressed. It was given to her as a tazbi by the opperwallahs, the neighbors upstairs and Ameneh marvels at how Pakistanis bend everything to the service of religiosity, even technology. She recites and counts, while she watches a cricket game in the street pre-dawn during Ramzan and makes her final decision to return to the US. Her daughter, who wants to do good here, will stay on, but is so naïve and out of touch and will learn a painful lesson later. And leave. I had meant it to symbolize everything that it did. I had completed the novel and it would be published almost a decade later.

The photos I took were of a child in a black shalwar kameez, barefooted, a wooden crate for Pepsi or Coke behind him, place in front of a garbage heap, swinging his bat as the ball came in. The first photo shows him getting ready to bat, the second the ball coming in and the boy lifting the bat and the third him striking it. I had taken these with my large long lens Olympus camera on a Friday in Karachi in 1987 or early 1988. The camera did not have a timer or at least I didn’t know how to use it. So I was pretty amazed that I had captured these images when I had picked them up from the developer. I never knew what photo might turn out and what wouldn’t. And the joy of seeing these was so huge for me that I had the photos framed—mounted on wooden plaques. I thought these would be the perfect gift and our hero would be so pleased and charmed by this gift.

I stepped back inside the house for breakfast in the kitchen, which was made and then served to us by both Uncle and Auntie, I brought out the gift. These three photos were my pride possessions.

Uncle and Auntie’s teenage kids were there too. The atmosphere was warm and cheerful as always it was in this home. American football and baseball were more their game. Uncle told his children about our hero’s achievements. They listened politely but didn’t know much about those feats and anyway they were American kids—there was a baseball match on mute on the TV in the background.

Our peacock hero came in looking ragged. Rubbing his eyes and the bridge of his nose, trying to clear his throat. His eyes were slightly swollen. He complained loudly that he had a massive headache. He seemed in a foul mood and growled that his sinuses were killing him. He had been uncomfortable in the guest room. He hadn’t been able to sleep most of the night because of the dry air and his back was hurting. Anyway, he sat down.

I told him I had a gift for him—he frowned. Maybe the sinuses? He looked annoyed. I ignored the look and pushed the pile of three small plaques towards him. He took a look at them one by one and looked at me with annoyance and irritation—What are these, he said in a tone which made me feel ashamed of what I’d given him. But I quickly recalibrated my shame to interpret his tone with me as being the same as of an irritated older brother. So it was really an honor to be the recipient of such churlish behavior from our hero.

I told him the whole story. He got even more annoyed it seemed. Angry. And the conversation that ensued went something like this:

“What is this! This is not the game I play!’ he said, shoving the photos back towards me with a clatter on the marble surface of the breakfast table. I think he actually tossed them back at me like frisbees. “Look at his posture, look at how he’s holding the bat, no shoes, and the garbage!”

I could barely breath. I felt heat rising up my throat into my face. The kids around the table looked astonished at the behavior.

“It is that game! And this is how kids play in the streets of Karachi,” I shoved the pile back at him. I was really taken aback. My legs felt as if they’d turned to stone. I felt my gut clench.

“No, it is not the game I play. It is played at Aitchison, and in the park in my neighborhood. Look at the condition of this boy—look how he is holding the bat and that is not even the proper ball, its a tennis ball.” It seemed to me that the peacock hero was insulted by an eight year old kid’s image.

He seemed totally unaware that he had crossed any lines. And he had absolutely no social radar or care for reading the room. But I can’t remember if he accepted the photos or not—I should have taken them back, but I didn’t. So I don’t know if he shoved them into his valise and took them with him or not.

I remember that he had stretched out the mean. And said something like I mean, you can’t tell who’s who over here. Any nobody can become somebody here if they have money. One doesn’t know who anyone is. I mean what is their background?

That afternoon we left for New York City. Uncle was going to drop me off first and then drop ‘my hero-no-more’ to where he was staying in NYC. In the car, with me in the back and hero-no-more sulking in the front, Uncle talked to him enthusiastically and with much wisdom to impart about the proposed hospital and hero-no-more took notes in a leather-bound diary balanced on his leg. We stopped at a gas station and Uncle got out to fill gas.

Hero-no-more draped his arm languidly over the back of the driver’s seat as he sat spread out in his seat. With his other hand he tapped the diary with his expensive looking pen.

He gazed out of the window at people filling gas in their cars. As I remember it, he had a pensive yet arrogant tone and asked if I knew what the problem was with America. Something like, you know what the problem is with this country? He had said the ‘you know’ in a sing song tone like he had discovered some hidden truth. I was upset about the shunning of my gift earlier, but at the same time the tone suggested that I was about to be the recipient of a confidence. I was angry and yet grateful. So I managed to ask frostily “No, I don’t know what the problem is with this country, but I’m sure you’ll tell me.”

He drawled something like this: just between you and me, it’s not like Velayat. It’s not like there in England here, is it? I had asked him what he had meant. Did he mean America was the land of opportunity? I remember that he had stretched out the mean. And said something like I mean, you can’t tell who’s who over here. Any nobody can become somebody here if they have money. One doesn’t know who anyone is. I mean what is their background? I felt that his tone was arrogant, sneering, yet all the while straightforward, innocent.

What did he mean? Was he admiring this aspect or sneering at it? He had used the word problem and not the word difference. He hadn’t said; you know what I’ve noticed as a difference between the US and the UK? No. He called it a problem. Wow. Was this commentary of his a reflection on the gathering the night before of well to do Pakistani doctors who did not have Aitchisonian and other private school English accents? They weren’t heirs and heiresses, barons and dukes. His kind of people. The gathering had been of open, generous and kind and very accomplished professionals. He had crossed a line.

I have to respect the sentiment and fervor of those who even now might consider him their idol. They are newly not apolitical and newly not supporting a military dictatorship. So, they are truly heartbroken to have reality hit them like a fast ball bouncer without a face guard in place.

It would take a decade or more for him to fully recognize the usefulness of the Pakistani diaspora, specifically their resources in helping him attain his bucket list dream of becoming Primo-Supremo-Hero.

At that time, and in that moment, the behavior earlier in the day which I had chalked up to sinuses acting up when he tossed the photos back at me and this little ‘just between you and me’ added up in my skewed perspective to an informality of a friend. And in a moment of dazed confusion, I felt grateful to have been chosen to receive this observation. I was grateful because this meant I was not included in those he looked down upon. I had been included in the inner thinking of ‘people like us’ looking down upon others. Can you believe it? What would you call this type of muddled thinking?

I thought about the photos that he had sneered at. They had been precious to me. But now I thought how wrong I was. The photos were so meaningless that I hadn’t even bothered to take them back or see if they had been left in his room. I could’ve retrieved them. But I felt a pride to have been chosen for his observations of what was wrong with America—prosperous fellow Pakistanis.

I have immense respect, empathy and care for the millions of people who adore my hero-no-more. Because he is their first love ever as a primo supremo. They’ve had decades of a relentless sense of collective victimhood and humiliation. Collectively felt accused of 9/11, and found relief for their humiliations in 24/7 cricket, religiosity and their hero-primo-supremo. Now they want him as their own Captain or a modern Caliph, who might decree that everyone ought to play cricket and listen to sacred recitations and songs in his praise on YouTube and TikTok through the night. Or maybe they want him as their own King Charles, or more aptly, Aurangzeb.

In terms of policy—he merely changed the name of one of the finest social programs in the world to something which sounds more like a good brand name for a condom rather than a government safety net program. And still on policy, consider what his government did to primary education textbooks and curriculum. If that is allowed to stand, then that is surely a bigger catastrophe than a peacock being stolen, or a house being set on fire. He will have literally burnt down the house, if that is allowed to stand.

I have to respect the sentiment and fervor of those who even now might consider him their idol. They are newly not apolitical and newly not supporting a military dictatorship. So, they are truly heartbroken to have reality hit them like a fast ball bouncer without a face guard in place. And in the diaspora, his followers are living in a virtual Pakistan of talk shows beamed in from there into their living rooms sponsored by real estate ads for apartments and gated housing communities aimed at them to ‘invest’ in Pakistan. Housing developments on land grabbed from the poor to build these imagined paradise homelands. They are enraged, though they are more likely to vote in American or British elections than in any in Pakistan.

I think of my hero-no-more without a container to stand on, contained on YouTube, holding on to his faded image, his perfectly blowdried jet-black dyed hair in his daily appearances. That hair would need tending, say every two weeks? So that’s six times of dying fearlessly for the revolution already while he’s been holed up for almost three months in his home. Can you picture it? I feel so sorry for the ‘Mor Commodore.’ Poor kid. I hope the only hardship he’s facing in prison is the derision of his captors doubling up laughing at his innocence.

But the innocence of my hero-no-more has not been as harmless as nabbing a peacock. He has lost the plot with his bucket list, instead fearfully donning a bucket over his head outdoors while political pontificating and preening indoors. And all the while telling his workers to sacrifice themselves, but asking his own kids to stay safely outside of Pakistan.

Call him a hero, or call him a tone-deaf hero-no-more, it doesn’t matter now does it? The dye has been cast.