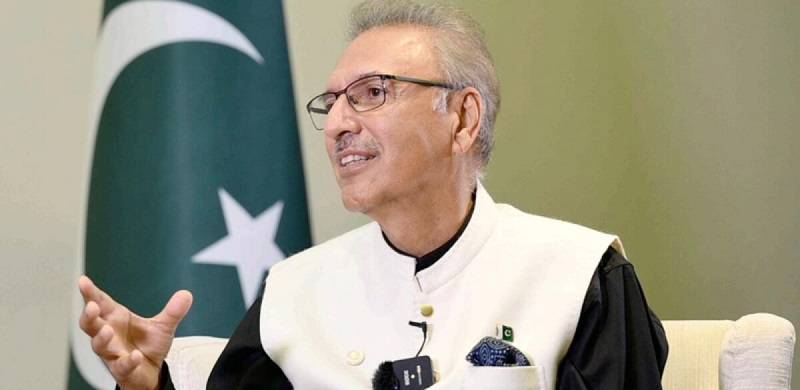

If the existing political and constitutional morass bedeviling the country was not serious enough, President Dr Alvi has written a letter to Chief Justice Umar Bandial seeking the establishment of a judicial commission to investigate Lettergate. This unprecedented step has been taken by the president of his own volition and not, as mandated by the constitution, on the advice of the cabinet/prime minister. It is for this reason that the highly irregular letter is couched in terms of a request – the president obviously having no constitutional right to require the Supreme Court to set up such a commission.

Many Pakistanis could think on the following lines: so what if the president has written such a letter; after all, isn’t he the head of state and does he not have the right to raise matters of public interest, whether in general terms or through a specific request to the Supreme Court, as in the present instance? Such simplistic and naïve thinking among fellow citizens may be particularly prevalent in the present turbulent times, what with the previous prime minister dangerously playing to the gallery by his constant assault on the edifice of the state and the constitution.

Therefore, in such a warped political environment, which effectively amounts to open season on the constitution, the president’s letter to the Supreme Court may not even seem like a minor infraction to those who are swallowing the Kaptaan’s flawed narrative, hook, line and sinker. But in actual fact this presidential action amounts to a blatant constitutional deviation and it must be called out as such!

The original framers of our constitution did not intend the president to become a rival centre of power to the prime minister – in the mould of interventionist heads of state like Malik Ghulam Mohammed and Syed Iskander Ali Mirza – therefore they made the president a figure-head who was bound to act on the advice of the prime minister in nearly every issue, save in very limited circumstances. This conception of presidential powers was in keeping with the tradition and spirit of parliamentary democracy.

Bonapartist Generals Zia-ul-Haq and Pervez Musharraf distorted the principle of a figure-head president so that they could retain effective powers in their hands as head-of-state even after they had introduced a fig-leaf of parliamentary democracy. The 18th Amendment to the constitution brought the pendulum back in favour of parliamentary democracy and the role of the president was once again consigned to that of a ceremonial figurehead.

The constitution, as it stands today, very clearly states that the president shall (emphasis added), in the exercise of his functions, act on and in accordance with the advice of the cabinet or the prime minister (Article 48(1)). The only exception to the rule laid down in Article 48(1) is provided by Article 48(2), which stipulates that the president shall act in his discretion in respect of any matter in respect of which he is empowered by the constitution to do so.

Therefore, the basic principle that emerges from Article 48 is that the president is bound to act on the advice of the cabinet/prime minister on all matters save those exceptional circumstances in which the constitution specifically gives him the power to exercise his discretion. In actual fact, after the passage of the 18th Amendment to the constitution most of the president’s discretionary powers have been abolished. The remaining areas of presidential discretion, which are few and far between, include the president’s power to dissolve the National Assembly in circumstances where a vote of no-confidence has been passed against the prime minister and no other member of the assembly can command a majority of its members (Article 58(2)), or the power to ask the prime minister to continue to hold office until his successor enters into office (Article 94).

However, there is no specific provision in the constitution which gives the president the discretionary power to put pen to paper and to approach the Supreme Court with a request to form a judicial commission in any matter, leave alone an issue as controversial and contentious as Lettergate. In the absence of such a discretionary power, the president is bound, under Article 48(1), to act on the advice of the cabinet/prime minister in the matter of Lettergate. Since there is nothing to suggest that the president has been advised by the cabinet/prime minister to make the request of the Supreme Court, then the obvious conclusion to be drawn is that Dr Alvi has violated the constitution by writing the letter to the CJP.

Why has the president taken this step? The reasons are obvious: first, he is unable or unwilling to fathom that he is a required to be an apolitical head of state and not a loyal apparatchik of the PTI; second, he does not seem to understand that he is subservient to the constitution and bound by the limitations that this supreme law places on his office; and, third, he appears to be ignorant of the concept of parliamentary democracy whereby he is essentially a ceremonial head of state.

Sadly, Dr Alvi’s action, which amounts to playing foot-loose and fancy free with the constitution, is just a reflection of the PTI’s overall disdain for constitutional supremacy. Time and again, the party’s top leadership has given ample proof of their tendency to brazenly breach the law that holds the federation together. Their most egregious display of disregard for the constitution occurred on 3rd April, when Deputy Speaker Suri ruled the no-confidence motion against the prime minister out of order on spurious grounds, and the prime minister promptly used this pretext to advise the president to dissolve the assembly, which the latter did without batting an eyelid. The resounding slap-down handed to them by the Supreme Court a few days later showed the extent of the audacity and contumaciousness with which Imran Khan and Co had treated the constitution. But, amazingly, they remain unrepentant.

If he has any little regard for the sanctity of his office, the head of state should pause and reconsider the dubious propriety of writing to the Supreme Court on Lettergate. His oath of office requires, and the nation expects, that he remains above the fray of dirty politics and does not act as the cat’s paw of a political party. His immediate predecessor, a simple and humble man, correctly adopted an apolitical mien while in office, even though he had been a PML-N leader of many years standing before becoming president. Aware of the fact that his former party was bitter about the unfair hand dealt to them during the controversial 2018 elections, President Mamnoon Hussain still did the right thing by the constitution, and he never once took any step in support of the PML-N’s narrative in the one month or so in which he worked with Imran Khan as prime minister. Consequently, he left office without having tarnished the credibility of his high office.

Can Dr Alvi take a leaf out of his predecessor’s book or is he hell-bent to expose himself to the devastating judgment of history for being a partisan and political president? The choice is his to make!

Many Pakistanis could think on the following lines: so what if the president has written such a letter; after all, isn’t he the head of state and does he not have the right to raise matters of public interest, whether in general terms or through a specific request to the Supreme Court, as in the present instance? Such simplistic and naïve thinking among fellow citizens may be particularly prevalent in the present turbulent times, what with the previous prime minister dangerously playing to the gallery by his constant assault on the edifice of the state and the constitution.

Therefore, in such a warped political environment, which effectively amounts to open season on the constitution, the president’s letter to the Supreme Court may not even seem like a minor infraction to those who are swallowing the Kaptaan’s flawed narrative, hook, line and sinker. But in actual fact this presidential action amounts to a blatant constitutional deviation and it must be called out as such!

The original framers of our constitution did not intend the president to become a rival centre of power to the prime minister – in the mould of interventionist heads of state like Malik Ghulam Mohammed and Syed Iskander Ali Mirza – therefore they made the president a figure-head who was bound to act on the advice of the prime minister in nearly every issue, save in very limited circumstances. This conception of presidential powers was in keeping with the tradition and spirit of parliamentary democracy.

Bonapartist Generals Zia-ul-Haq and Pervez Musharraf distorted the principle of a figure-head president so that they could retain effective powers in their hands as head-of-state even after they had introduced a fig-leaf of parliamentary democracy. The 18th Amendment to the constitution brought the pendulum back in favour of parliamentary democracy and the role of the president was once again consigned to that of a ceremonial figurehead.

The constitution, as it stands today, very clearly states that the president shall (emphasis added), in the exercise of his functions, act on and in accordance with the advice of the cabinet or the prime minister (Article 48(1)). The only exception to the rule laid down in Article 48(1) is provided by Article 48(2), which stipulates that the president shall act in his discretion in respect of any matter in respect of which he is empowered by the constitution to do so.

Therefore, the basic principle that emerges from Article 48 is that the president is bound to act on the advice of the cabinet/prime minister on all matters save those exceptional circumstances in which the constitution specifically gives him the power to exercise his discretion. In actual fact, after the passage of the 18th Amendment to the constitution most of the president’s discretionary powers have been abolished. The remaining areas of presidential discretion, which are few and far between, include the president’s power to dissolve the National Assembly in circumstances where a vote of no-confidence has been passed against the prime minister and no other member of the assembly can command a majority of its members (Article 58(2)), or the power to ask the prime minister to continue to hold office until his successor enters into office (Article 94).

However, there is no specific provision in the constitution which gives the president the discretionary power to put pen to paper and to approach the Supreme Court with a request to form a judicial commission in any matter, leave alone an issue as controversial and contentious as Lettergate. In the absence of such a discretionary power, the president is bound, under Article 48(1), to act on the advice of the cabinet/prime minister in the matter of Lettergate. Since there is nothing to suggest that the president has been advised by the cabinet/prime minister to make the request of the Supreme Court, then the obvious conclusion to be drawn is that Dr Alvi has violated the constitution by writing the letter to the CJP.

Why has the president taken this step? The reasons are obvious: first, he is unable or unwilling to fathom that he is a required to be an apolitical head of state and not a loyal apparatchik of the PTI; second, he does not seem to understand that he is subservient to the constitution and bound by the limitations that this supreme law places on his office; and, third, he appears to be ignorant of the concept of parliamentary democracy whereby he is essentially a ceremonial head of state.

Sadly, Dr Alvi’s action, which amounts to playing foot-loose and fancy free with the constitution, is just a reflection of the PTI’s overall disdain for constitutional supremacy. Time and again, the party’s top leadership has given ample proof of their tendency to brazenly breach the law that holds the federation together. Their most egregious display of disregard for the constitution occurred on 3rd April, when Deputy Speaker Suri ruled the no-confidence motion against the prime minister out of order on spurious grounds, and the prime minister promptly used this pretext to advise the president to dissolve the assembly, which the latter did without batting an eyelid. The resounding slap-down handed to them by the Supreme Court a few days later showed the extent of the audacity and contumaciousness with which Imran Khan and Co had treated the constitution. But, amazingly, they remain unrepentant.

If he has any little regard for the sanctity of his office, the head of state should pause and reconsider the dubious propriety of writing to the Supreme Court on Lettergate. His oath of office requires, and the nation expects, that he remains above the fray of dirty politics and does not act as the cat’s paw of a political party. His immediate predecessor, a simple and humble man, correctly adopted an apolitical mien while in office, even though he had been a PML-N leader of many years standing before becoming president. Aware of the fact that his former party was bitter about the unfair hand dealt to them during the controversial 2018 elections, President Mamnoon Hussain still did the right thing by the constitution, and he never once took any step in support of the PML-N’s narrative in the one month or so in which he worked with Imran Khan as prime minister. Consequently, he left office without having tarnished the credibility of his high office.

Can Dr Alvi take a leaf out of his predecessor’s book or is he hell-bent to expose himself to the devastating judgment of history for being a partisan and political president? The choice is his to make!