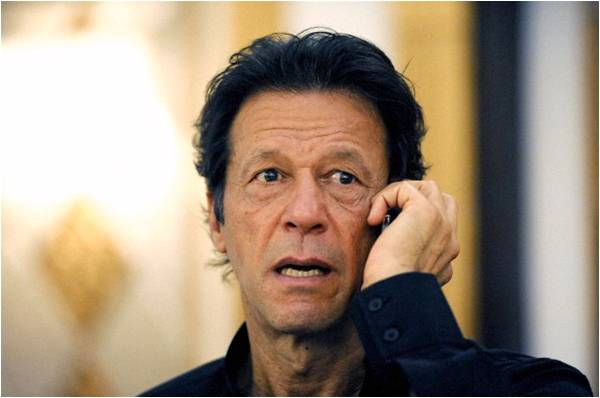

Imran Khan’s changing stance has disappointed his critics and followers alike. His latest somersault on the demand for the prime minister’s resignation is being seen as the mother of all U-turns.

Since arriving in Islamabad three months ago, the Tehrik-e-Insaf chairman and his followers refused to budge from a maximalist position. They believed an investigation into their rigging allegations would not be fair because Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif would influence the process. In countless talk shows, press conferences and speeches, that argument remained a keystone of the anti-Nawaz movement.

Sane voices in the media, politics and the legal fraternity agreed with his demand for an impartial investigation, they did not subscribe to the idea of punishing the prime minister or anyone else on the basis of mere allegations.

For three months, Mr Khan and his lieutenants scoured newspapers and annals of history to give examples of politicians who resigned while facing different allegations. They demanded a similar high moral ground from the prime minister.

At a public rally in Rahimyar Khan on November 9, the PTI chairman backtracked from the demand of the prime minister’s resignation. He agreed to let a Supreme Court commission complete the probe in four to six weeks. Then he added a strange new demand – inclusion of officials of Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and Military Intelligence (MI) in the commission.

Only Mr Khan knows why intelligence officials should sit with Supreme Court judges to look into the allegations of electoral rigging. However, other political parties rejected the proposition.

Finance Minister Ishaq Dar said it was constitutionally and legally impossible to have intelligence officials in the judicial commission. The People’s Party leadership shared his opinion. Eminent lawyer Babar Sattar endorsed their viewpoint too.

While Mr Khan places his faith in the ISI, he also accuses PM Sharif of taking bribes from the same agency in 1990.

The PTI chairman wanted action against corrupt politicians who had received bribes from the ISI, as admitted by former military men in the famous Asghar Khan case. For reasons best known to himsef, he never asked to punish the ISI officials who distributed the money in the first place.

Mian Mehmoodur Rasheed of the PTI says the recent flexibility must not be misunderstood as their weakness. He asserted that the PML-N government would not survive next year if transparent investigations were not conducted.

Sources in the PTI revealed it was not an easy decision to withdraw from the demand of the prime minister’s resignation. The PTI core committee deliberated on the matter and found themselves on a rather slippery slope. The sit-in at D-chowk failed to serve the purpose, the third force refused to intervene, and the other political parties rejected Mr Khan’s anti-democracy narrative.

PTI MNAs and MPAs, especially those who were elected for the first time, loathed the idea of resigning from the assemblies. Mr Khan opened too many fronts to properly concentrate on either. In a recent statement, he did not even spare his only ally Sirajul Haq.

Then someone – not Sheikh Rashid – whispered into his ear that his maximalist position was bailing the Sharifs out. The ideal thing at the moment for the PTI is to get the investigations started and capitalize on it.

The PTI now plans to regroup in Islamabad with more passion and vigor on November 30. After the return of Tahirul Qadri, the PTI sit-in has turned into a joke.

As usual, the Sharif cabinet, comprised of too many ostriches, is not sure how series the threat is or how to deal with Mr Khan’s new ultimatum.

The non-seriousness of the federal government is evident from its failure to appoint a full-time Chief Election Commissioner. It only showed alacrity to meet the deadline set by the apex court.

Developing a consensus on the future CEC was not an easy task to begin with. The 18th constitutional amendment empowers the prime minister and the opposition leader to appoint the CEC. However, the controversial nature of the circumstances compelled them to take other political parties including the PTI on board.

Justice Rana Bhagwandas refused to take the job, like some other judges who were approached. Thanks to Mr Khan’s diatribes, no person of good reputation would want to be in a position where their image will be tarnished in public.

The PTI chairman was on the record praising ex-chief justice Tasaduq Hussain Jilani. “I can trust Justice Tasaduq Jilani and Justice Nasirul Mulk with my eyes closed,” he told an interviewer a few months ago. In his Rahimyar Khan speech he said he did not trust him and he should not become the chief election commissioner.

Under Article 213 of the Constitution only a serving or retired Supreme Court judge or a person who qualifies to become an apex court judge can be appointed as CEC.

The judicial history of Pakistan is as murky as political history. The judiciary has validated martial laws and allowed dictators to amend the constitution in the past. Gen Musharraf appointed then chief justice Irshad Hassan Khan as CEC, in January 2002, and he was accused of helping the military regime rig the general elections nine months later.

Conducting the elections is a mammoth administrative job. Indian politicians realized that rather quickly, and appointed the best civil servants having an administrative background for the job.

“Our judges are honest and respectful. But this shouldn’t be the only criterion for the chief election commissioner,” says former interior secretary Tasneem Noorani. “Here we are talking about an honest person with great administrative skills.”

Veteran journalist Amir Mateen agrees. He says Article 213 limits the options. Someone who had spent most of their time in the field could better understand the intricacies, he says, and there should be no difficulty in amending the article in days, if all the political parties agree.

The appointment of a CEC in haste will merely aggravate the situation.

Shahzad Raza is an Islamabad-based journalist

Twitter: @shahzadrez

Since arriving in Islamabad three months ago, the Tehrik-e-Insaf chairman and his followers refused to budge from a maximalist position. They believed an investigation into their rigging allegations would not be fair because Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif would influence the process. In countless talk shows, press conferences and speeches, that argument remained a keystone of the anti-Nawaz movement.

Sane voices in the media, politics and the legal fraternity agreed with his demand for an impartial investigation, they did not subscribe to the idea of punishing the prime minister or anyone else on the basis of mere allegations.

Why should intelligence officials sit with Supreme Court judges?

For three months, Mr Khan and his lieutenants scoured newspapers and annals of history to give examples of politicians who resigned while facing different allegations. They demanded a similar high moral ground from the prime minister.

At a public rally in Rahimyar Khan on November 9, the PTI chairman backtracked from the demand of the prime minister’s resignation. He agreed to let a Supreme Court commission complete the probe in four to six weeks. Then he added a strange new demand – inclusion of officials of Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and Military Intelligence (MI) in the commission.

Only Mr Khan knows why intelligence officials should sit with Supreme Court judges to look into the allegations of electoral rigging. However, other political parties rejected the proposition.

Finance Minister Ishaq Dar said it was constitutionally and legally impossible to have intelligence officials in the judicial commission. The People’s Party leadership shared his opinion. Eminent lawyer Babar Sattar endorsed their viewpoint too.

While Mr Khan places his faith in the ISI, he also accuses PM Sharif of taking bribes from the same agency in 1990.

The PTI chairman wanted action against corrupt politicians who had received bribes from the ISI, as admitted by former military men in the famous Asghar Khan case. For reasons best known to himsef, he never asked to punish the ISI officials who distributed the money in the first place.

Mian Mehmoodur Rasheed of the PTI says the recent flexibility must not be misunderstood as their weakness. He asserted that the PML-N government would not survive next year if transparent investigations were not conducted.

Sources in the PTI revealed it was not an easy decision to withdraw from the demand of the prime minister’s resignation. The PTI core committee deliberated on the matter and found themselves on a rather slippery slope. The sit-in at D-chowk failed to serve the purpose, the third force refused to intervene, and the other political parties rejected Mr Khan’s anti-democracy narrative.

PTI MNAs and MPAs, especially those who were elected for the first time, loathed the idea of resigning from the assemblies. Mr Khan opened too many fronts to properly concentrate on either. In a recent statement, he did not even spare his only ally Sirajul Haq.

Then someone – not Sheikh Rashid – whispered into his ear that his maximalist position was bailing the Sharifs out. The ideal thing at the moment for the PTI is to get the investigations started and capitalize on it.

The PTI now plans to regroup in Islamabad with more passion and vigor on November 30. After the return of Tahirul Qadri, the PTI sit-in has turned into a joke.

As usual, the Sharif cabinet, comprised of too many ostriches, is not sure how series the threat is or how to deal with Mr Khan’s new ultimatum.

The non-seriousness of the federal government is evident from its failure to appoint a full-time Chief Election Commissioner. It only showed alacrity to meet the deadline set by the apex court.

Developing a consensus on the future CEC was not an easy task to begin with. The 18th constitutional amendment empowers the prime minister and the opposition leader to appoint the CEC. However, the controversial nature of the circumstances compelled them to take other political parties including the PTI on board.

Justice Rana Bhagwandas refused to take the job, like some other judges who were approached. Thanks to Mr Khan’s diatribes, no person of good reputation would want to be in a position where their image will be tarnished in public.

The PTI chairman was on the record praising ex-chief justice Tasaduq Hussain Jilani. “I can trust Justice Tasaduq Jilani and Justice Nasirul Mulk with my eyes closed,” he told an interviewer a few months ago. In his Rahimyar Khan speech he said he did not trust him and he should not become the chief election commissioner.

Under Article 213 of the Constitution only a serving or retired Supreme Court judge or a person who qualifies to become an apex court judge can be appointed as CEC.

The judicial history of Pakistan is as murky as political history. The judiciary has validated martial laws and allowed dictators to amend the constitution in the past. Gen Musharraf appointed then chief justice Irshad Hassan Khan as CEC, in January 2002, and he was accused of helping the military regime rig the general elections nine months later.

Conducting the elections is a mammoth administrative job. Indian politicians realized that rather quickly, and appointed the best civil servants having an administrative background for the job.

“Our judges are honest and respectful. But this shouldn’t be the only criterion for the chief election commissioner,” says former interior secretary Tasneem Noorani. “Here we are talking about an honest person with great administrative skills.”

Veteran journalist Amir Mateen agrees. He says Article 213 limits the options. Someone who had spent most of their time in the field could better understand the intricacies, he says, and there should be no difficulty in amending the article in days, if all the political parties agree.

The appointment of a CEC in haste will merely aggravate the situation.

Shahzad Raza is an Islamabad-based journalist

Twitter: @shahzadrez