Our path leads through the poetry of machines,

from the bungling citizen to the perfect electric man.

In revealing the machine’s soul, in causing the worker to love his workbench, the peasant his tractor, the engineer his engine ---

we introduce creative joy into all mechanical labour,

we bring people into closer kinship with machines,

we foster new people.

The new man, free of unwieldiness and clumsiness, will have the light, precise movement of machines, and he will be the gratifying subject of our films.

Openly recognising the rhythm of machines, the delight of mechanical labor, the perception of the beauty of chemical processes,

We sing of earthquakes, we compose film epics of electric power plants and flame, we delight in the movements of comets and meteors and the gestures of searchlights that dazzle the stars.

Everyone who cares for his art seeks the essence of his own technique.

Cinema’s unstrung nerves need a rigorous system of precise movement.

The meter, tempo, and type of movement, as well as its precise location with respect to the axes of a shot’s coordinates and perhaps to the axes of universal coordinates (the three dimensions + the fourth-time), should be studied and taken into account by each creator in the field of cinema.

Radical necessity, precision, and speed are the three components of movement worth filming and screening.

The geometrical extract of movement through an exciting succession of images is what’s required of montage.

Freed from the boundaries of time and space,

I coordinate any and all points of the universe wherever I want them to be

My way leads towards the creation of a fresh perception of the world

Thus I explain in a new way, the world unknown to you

Those words are from a 1923 manifesto conceived by Soviet film director Dziga Vertov.

His 1929 film Man With A Movie Camera is his groundbreaking project that manifests the ethos of his 1923 manifesto: the attempt at getting the perfect shot. The film doesn’t have a conventional plot, as Vertov solely relied on the tempo of the film to transform itself into narrative. This very idea of making use of a formal element of a medium (tempo in this case) to convey meaning was in itself quite an innovative, revolutionary style that explored the potential of the film as a medium by pushing its boundaries.

Many films at that time were story-based and had a conventional plot. As a Soviet director, Vertov believed fictional cinema was elitist and unsympathetic to the Communist cause because it created a fake reality. Consequently, he rejected the elements and tools that were used to create it. He felt that film was stuck in this cycle of making something so formulaic that it was limiting the art form itself. Thus, his concerns were more inclined towards:

- the idea of the camera; and

- what the camera can achieve.

The camera was not only a tool, but a part of the cameraman’s body. The industrialised Soviet Union was rising and that was constantly shown with people working in mines, telephone operators to cigarette packagers. The camera was the eye interacting with the civilians, the machine and human working as one. Letting the viewer see that it was a film within a film added a new layer to an already complex film. Self-awareness was an added element that was not relevant or used in too many silent films.

This unorthodox approach of Vertov, in my view is an extension of Impressionism, the first movement in the canon of modern art that had a massive effect on the development of art in the 20th century. Like most revolutionary styles, Impressionism received great criticism initially, at the hands of the Salon of the Académie des Beaux-Arts which dominated the French art scene back then. It was gradually absorbed into the mainstream.

The Impressionists, unlike the Romantics, didn’t paint idealised landscapes void of anything distracting or manmade. Instead, they would paint the landscapes as they saw them, including railroads, factories or anything else that could be considered by some to be marring the view. Impressionists were also deeply influenced by photography. Often their paintings could be described as being like a photograph, in that they depicted objects in motion rather than just static and still. They were interested in capturing fleeting events: for instance, the atmosphere of a particular time of day or the effects of different weather conditions on their subject. Thus, it dealt with a more sensorial aspect of seeing i.e. self-awareness, intrinsic to Vertov’s approach to cinema.

Lahore to Rome (1-9 0ctober 2022)

This serial approach to subject-matter, and moreover, this criticality or critical examination of the very act of seeing and how various natural external factors contribute to the shift in perception overtime, forms the basis of Lahore based artist Faizan Naveed’s Art.

His visceral style and sensibilities towards image viewing and image formulation enable him to embrace the essence of reality-- raw, crude and dynamic, something he shares with his aforementioned predecessors, the late 19th-century French Impressionists and early 20th-century Soviet filmmaker and film theorist Dziga Vertov. Sometimes, even the most avant-garde artists need the security of knowing that the path they have chosen to follow has some roots in tradition.

The visceral effect of an image depends on our emotions and interpretation of life itself. An image can have more than one meaning, and can be seen differently from person to person. In this regard Faizan claims that if photography is a record of what is seen, he is interested in how he sees it. For him it’s an “exploration of pluralities.”

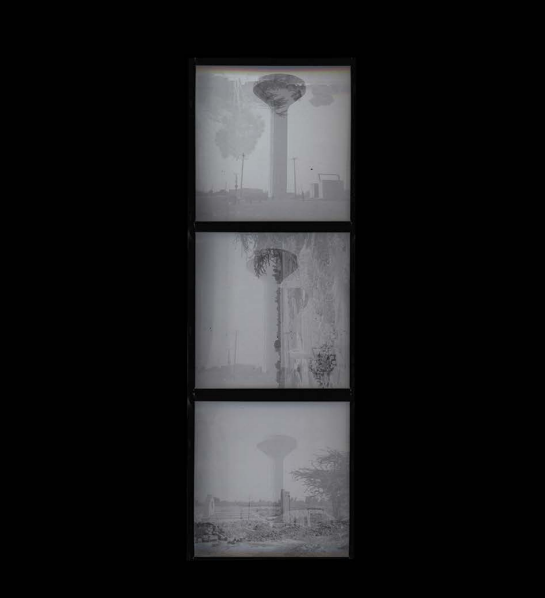

The artist assumed the role of a pivot and began capturing what was in front of him and what lay behind. The outcomes were interesting amalgamations of a graveyard with an extraterrestrial futuristic form stemming from it

His recent solo exhibition in a 16th-century castle situated on the outskirts of Rome was part of the 10th edition of “Castelnuovo Fotografia,” under the patronage of the Embassy of Pakistan in Italy, curated by Manuela De Leonardi. It marked the culmination of his ongoing black and white photographic series titled “Autumn leaves”, that he has been pursuing for the past seven years, whereby he assumes the role of a mediator between the camera and his immediate surroundings. He reads each negative frame as a fragment of memory in space and time, which along with multiple other fragments of the same view give rise to a multilayered, multidimensional image with varying opacities of the subject. The reconfigured fragments are such that they imitate one another, but coalesce into photo-montages eventually.

It is the form that transcends into the idea, this duplication of the subject i.e. individuals with varying transparencies gives rise to multiple interpretations. A very simplistic reading of it could be the process of human evolution. However the artist interprets these duplicates as multiple reflections of an individual, all in one image.

Just as he weaves together an image, his image knits together the relationship of an individual with his ever-changing surroundings, a consequence of rapid urbanisation. Formally speaking, the duplication results in movement of the eye within the picture frame that challenges the convention of perspective, which is unique to Western painting. This creates an ironic yet interesting dichotomy whereby his encounter with reality is similar to that of a 19th-century painter, yet the outcomes completely neglect certain defining/distinctive aspects of modern European art.

This conscious attempt of relocating more than one image, in more than one place, at more than one time, is also evident in a similar earlier series of black and white photographic prints titled “Between here and there,” that was also on display in the Rome photography exhibit. For this series, the artist assumed the role of a pivot and began capturing what was in front of him and what lay behind. The outcomes were interesting amalgamations of a graveyard with an extraterrestrial futuristic form stemming from it - actually a cement water storage tank for the housing society that was in process of completion. The Interplay of “The Final Resting place” and “The house of our dreams” explores the tension between fate and the Imagined, in the process revealing the fragility of life and the tenderness of dreams manifested in these incomplete structures.

“Seven years of prolonged engagement with the black and white must have reshaped your perception of colour,” I asked the artist, to which he replied:

“A colour’s very existence is based on how other colours are understood. Placing black and white images next to coloured ones give us another chance to relook, rethink and re-examine what we see and what we already know.”