Since taking power in 2013, the PML-N government has stabilized the Pakistani economy. A nascent recovery is taking place on the back of government-supported infrastructure spending. All major indicators to measure economic growth and stability, such as top line GDP growth, currency stability, and inflation have improved. The rupee has stabilized, inflation is at record lows, and the stock market is a global top performer. The outlook for the economy looks quite rosy, or so it seems.

With stability restored, Pakistan is set to successfully complete its first International Monetary Fund (IMF) program. The last ten IMF programs were all failures due to Pakistan’s inability to meet its commitments. These included privatization of state-owned enterprises, removal of subsidies, and cutting spending to meet budget deficit targets. In the most recent IMF program, the government has met most of its commitments to the fund. The one major exception is the failure to privatize state-owned assets such as the Pakistan International Airlines and the Pakistan Steel Mills.

With the IMF on its way out, some in the government have boasted that it will no longer be needed. The policies responsible for bringing about this recovery, however, have sown the seeds for the next economic crisis in Pakistan.

When we look under the hood it becomes quite obvious that this recovery has been built on shaky foundations. Economies are like households: excessive spending drains savings, and when they run out, one must rely on the aid of others for a bailout. When an economy begins to pay more for imports in foreign currency than what it earns, it begins to draw down its foreign reserves. Excessive drainage of these reserves leads to balance of payments crises, as the economy is unable to pay for foreign imports. As a result the country must seek bailouts from organizations such as the IMF. Such a crisis is brewing in Pakistan and the government that comes to power after elections in 2018 will have to contend with it.

Cheap oil: A missed opportunity

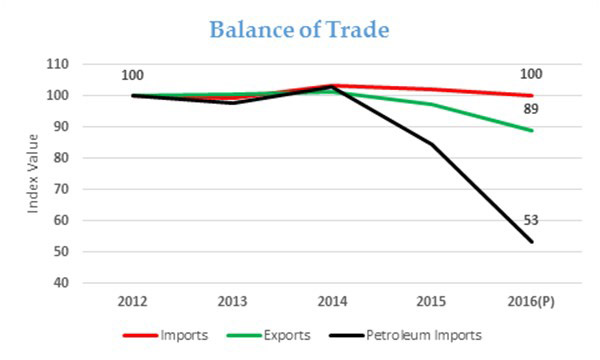

The crash in global oil prices in 2012 has provided Pakistan with a windfall of over $7 billion. According to data available from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), Pakistan’s petroleum imports fell from $14.3 billion in 2012 to $7.6 billion in 2016 (projected), a decline of over 45%. During the same period, however, the country has started importing a lot of other products from the rest of the world. As a result the import bill has remained flat: $40.3 billion in 2012 versus $40.4 billion in 2016 (projected).

During the same period, the country’s export figures have declined 11%: approximately $25 billion in 2012 versus $22 billion in 2016 (projected). The official view is that global economic headwinds and declining agricultural prices have led to this decline. While this may be true, other economies in the region have not fared so badly. According to World Bank data, Bangladesh’s exports rose by almost 29% from 2012 to $32.3 billion in 2015, and Sri Lanka’s exports also rose by almost 12% to $10.5 billion in 2015.

Pakistan has not been able to improve its trade position despite a considerable decline in oil prices. This is due to a lack of a robust export-promotion strategy and an inability to push sectoral reforms that could enable Pakistan’s industries to be more competitive internationally. The result is a continued dependency on other sources of foreign exchange to meet the economy’s import needs, such as petroleum products, consumer goods, and machinery. Worker remittances have provided the necessary funds, rising by over 50% since 2012 to $19.9 billion in 2016.

Low oil prices, however, will lead to a decline in future remittance inflows. A decline in oil revenue for Gulf economies, which provide almost 65% of remittance inflows to Pakistan, increases the likelihood that remittance inflows will fall in the coming years.

Failing to reform

The dramatic rise in oil prices, which saw the per barrel price of the commodity cross $100 in 2012, led to the balance of payments crisis witnessed towards the end of the last PPP government. From 2010 onwards, foreign reserves reached record lows and inflation hit a multi-year high. Since coming to power in 2013, the PML-N has been successful in shoring up foreign reserves. From a low of $3.6 billion in December 2013, Pakistan’s official liquid reserves, according to the State Bank, recovered to over $18 billion in June 2016.

Developing countries, especially those with substantial energy import needs like Pakistan, need strong foreign exchange reserves so that they can pay for their energy needs and keep the economy afloat. The usual formula for achieving this goal is quite simple: export more than you import. Pakistan has not followed this and its exports have declined in recent years. While remittances have increased, they are not high enough to increase foreign exchange reserves.

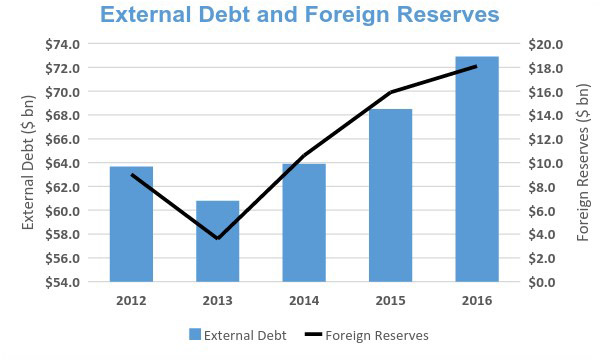

In the absence of strong export growth, the government has issued long-term external debt—this is money borrowed from multilateral agencies such as the IMF and the Asian Development Bank, or from the international bond market. At the end of 2013, when Pakistan’s reserves hit a low of $3.6 billion, the country’s total external debt stood at $60.8 billion. Since then, external debt has increased 20% to almost $73 billion. The IMF has provided $2.5 billion and the remainder has been borrowed from other sources, including the issue of $3 billion Euro and Sukuk bonds. On October 8, Pakistan issued $1b in a five-year sukuk bond to fill the trade gap. To be clear, there is nothing inherently wrong in issuing debt. Pakistan’s total external debt is less than 26% of GDP which is quite manageable.

The issue lies with failing to reform the economy during this period. The breathing room provided by low oil prices and a favorable interest rate environment should have been used to push structural reforms in the economy. That has not been the case, as evidenced by the rising import bill (after adjusting for low oil prices) and declining exports.

The next crisis: Repeating history

Time is running out for Pakistan to push through reforms that can prevent the next crisis. By 2020, global oil prices are expected to recover and will increase the country’s import bill. The International Energy Agency expects oil to fetch a price of $80 a barrel by 2020. This represents an increase of over 75% based on oil hovering around $45 a barrel today. Holding the quantity of petroleum imports constant, Pakistan’s petroleum import bill would rise by almost $6 billion from its current level of $7.6 billion. The result will be a drain on foreign exchange reserves similar to that witnessed during the tail-end of the PPP government.

The problem will be compounded by a rise in external financing needs for the country. According to IMF data, Pakistan’s external financing need will be over $13 billion a year from 2017 to 2020, hitting a high of $15 billion in 2019. Global interest rates, at record lows in recent years, have allowed Pakistan and other emerging markets to borrow at low yields. These are expected to rise in the next 12 to 24 months as the United States economy posts strong growth. The shift in policy will result in an outflow of funds from riskier emerging market debt to safer debt instruments in the developed world, limiting Pakistan’s ability to meet its financing needs at the most inopportune time.

The resulting crisis will be similar to the one witnessed a few years ago during the PPP’s tenure. The government that comes to power after the 2018 elections will run higher budget deficits, leading to increase in the rate of inflation. Large infrastructure and public-sector development programs will have to be cut. And the SBP will be forced to increase interest rates to curb inflation. The ensuing economic slowdown will further constrain the government’s revenue capacity and add to the budgetary woes.

Given the rise in external debt, the run on the rupee will be larger than what has been witnessed in prior instances. To stabilize the value of the currency, the PML-N government has allowed it to remain overvalued—the IMF has raised this issue in successive reports. In a crisis where reserves are declining rapidly, the rupee will come under profound pressure, leading to a remarkable depreciation in a short period of time.

The general population will be burdened with rising prices, a stagnant economy, and a decline in real wages. This will not be something new, for the economy has witnessed similar crises prior to each of the previous ten bailouts by the IMF.

Economists inside and outside Pakistan have written and spoken about this issue at length, and it does not take a doctorate in economics to recognize the challenges facing Pakistan’s economy. The government has taken some measures to attract investment into Pakistan, with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor being a cornerstone of the strategy. The failure, however, lies in not taking measures to prevent crises that could engulf the economy in the medium term.

The continued rise in imports and declining exports have been at the heart of every balance of payments crisis the country has seen. Given Pakistan’s dependence on foreign oil, rising oil prices play a central role in these crises. Experts have laid out policy measures to eliminate the structural inefficiencies plaguing the economy and enhance the country’s abilsity to build foreign exchange reserves. Without a long-term strategic vision that seeks to convert nascent recoveries into a sustained period of economic growth, Pakistan will continue to go from one crisis to another and continue to rely on the IMF. n

Uzair Younus is an analyst at Albright Stonebridge Group and can be reached at uzairmyounus@gmail.com

With stability restored, Pakistan is set to successfully complete its first International Monetary Fund (IMF) program. The last ten IMF programs were all failures due to Pakistan’s inability to meet its commitments. These included privatization of state-owned enterprises, removal of subsidies, and cutting spending to meet budget deficit targets. In the most recent IMF program, the government has met most of its commitments to the fund. The one major exception is the failure to privatize state-owned assets such as the Pakistan International Airlines and the Pakistan Steel Mills.

With the IMF on its way out, some in the government have boasted that it will no longer be needed. The policies responsible for bringing about this recovery, however, have sown the seeds for the next economic crisis in Pakistan.

When we look under the hood it becomes quite obvious that this recovery has been built on shaky foundations. Economies are like households: excessive spending drains savings, and when they run out, one must rely on the aid of others for a bailout. When an economy begins to pay more for imports in foreign currency than what it earns, it begins to draw down its foreign reserves. Excessive drainage of these reserves leads to balance of payments crises, as the economy is unable to pay for foreign imports. As a result the country must seek bailouts from organizations such as the IMF. Such a crisis is brewing in Pakistan and the government that comes to power after elections in 2018 will have to contend with it.

We are likely to need the IMF again. During a good run after 2013, the government failed to reform the economy. The breathing room provided by low oil prices and a favorable interest rate environment should have been used to push structural reforms in the economy

Cheap oil: A missed opportunity

The crash in global oil prices in 2012 has provided Pakistan with a windfall of over $7 billion. According to data available from the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), Pakistan’s petroleum imports fell from $14.3 billion in 2012 to $7.6 billion in 2016 (projected), a decline of over 45%. During the same period, however, the country has started importing a lot of other products from the rest of the world. As a result the import bill has remained flat: $40.3 billion in 2012 versus $40.4 billion in 2016 (projected).

During the same period, the country’s export figures have declined 11%: approximately $25 billion in 2012 versus $22 billion in 2016 (projected). The official view is that global economic headwinds and declining agricultural prices have led to this decline. While this may be true, other economies in the region have not fared so badly. According to World Bank data, Bangladesh’s exports rose by almost 29% from 2012 to $32.3 billion in 2015, and Sri Lanka’s exports also rose by almost 12% to $10.5 billion in 2015.

Pakistan has not been able to improve its trade position despite a considerable decline in oil prices. This is due to a lack of a robust export-promotion strategy and an inability to push sectoral reforms that could enable Pakistan’s industries to be more competitive internationally. The result is a continued dependency on other sources of foreign exchange to meet the economy’s import needs, such as petroleum products, consumer goods, and machinery. Worker remittances have provided the necessary funds, rising by over 50% since 2012 to $19.9 billion in 2016.

Low oil prices, however, will lead to a decline in future remittance inflows. A decline in oil revenue for Gulf economies, which provide almost 65% of remittance inflows to Pakistan, increases the likelihood that remittance inflows will fall in the coming years.

Failing to reform

The dramatic rise in oil prices, which saw the per barrel price of the commodity cross $100 in 2012, led to the balance of payments crisis witnessed towards the end of the last PPP government. From 2010 onwards, foreign reserves reached record lows and inflation hit a multi-year high. Since coming to power in 2013, the PML-N has been successful in shoring up foreign reserves. From a low of $3.6 billion in December 2013, Pakistan’s official liquid reserves, according to the State Bank, recovered to over $18 billion in June 2016.

Developing countries, especially those with substantial energy import needs like Pakistan, need strong foreign exchange reserves so that they can pay for their energy needs and keep the economy afloat. The usual formula for achieving this goal is quite simple: export more than you import. Pakistan has not followed this and its exports have declined in recent years. While remittances have increased, they are not high enough to increase foreign exchange reserves.

In the absence of strong export growth, the government has issued long-term external debt—this is money borrowed from multilateral agencies such as the IMF and the Asian Development Bank, or from the international bond market. At the end of 2013, when Pakistan’s reserves hit a low of $3.6 billion, the country’s total external debt stood at $60.8 billion. Since then, external debt has increased 20% to almost $73 billion. The IMF has provided $2.5 billion and the remainder has been borrowed from other sources, including the issue of $3 billion Euro and Sukuk bonds. On October 8, Pakistan issued $1b in a five-year sukuk bond to fill the trade gap. To be clear, there is nothing inherently wrong in issuing debt. Pakistan’s total external debt is less than 26% of GDP which is quite manageable.

The issue lies with failing to reform the economy during this period. The breathing room provided by low oil prices and a favorable interest rate environment should have been used to push structural reforms in the economy. That has not been the case, as evidenced by the rising import bill (after adjusting for low oil prices) and declining exports.

The dramatic rise in oil prices, which saw the per barrel price of the commodity cross $100 in 2012, led to the balance of payments crisis witnessed towards the end of the last PPP government

The next crisis: Repeating history

Time is running out for Pakistan to push through reforms that can prevent the next crisis. By 2020, global oil prices are expected to recover and will increase the country’s import bill. The International Energy Agency expects oil to fetch a price of $80 a barrel by 2020. This represents an increase of over 75% based on oil hovering around $45 a barrel today. Holding the quantity of petroleum imports constant, Pakistan’s petroleum import bill would rise by almost $6 billion from its current level of $7.6 billion. The result will be a drain on foreign exchange reserves similar to that witnessed during the tail-end of the PPP government.

The problem will be compounded by a rise in external financing needs for the country. According to IMF data, Pakistan’s external financing need will be over $13 billion a year from 2017 to 2020, hitting a high of $15 billion in 2019. Global interest rates, at record lows in recent years, have allowed Pakistan and other emerging markets to borrow at low yields. These are expected to rise in the next 12 to 24 months as the United States economy posts strong growth. The shift in policy will result in an outflow of funds from riskier emerging market debt to safer debt instruments in the developed world, limiting Pakistan’s ability to meet its financing needs at the most inopportune time.

The resulting crisis will be similar to the one witnessed a few years ago during the PPP’s tenure. The government that comes to power after the 2018 elections will run higher budget deficits, leading to increase in the rate of inflation. Large infrastructure and public-sector development programs will have to be cut. And the SBP will be forced to increase interest rates to curb inflation. The ensuing economic slowdown will further constrain the government’s revenue capacity and add to the budgetary woes.

The government that comes to power after the 2018 elections will run higher budget deficits, leading to increase in the rate of inflation. Large infrastructure and public-sector development programs will have to be cut. And the SBP will be forced to increase interest rates to curb inflation

Given the rise in external debt, the run on the rupee will be larger than what has been witnessed in prior instances. To stabilize the value of the currency, the PML-N government has allowed it to remain overvalued—the IMF has raised this issue in successive reports. In a crisis where reserves are declining rapidly, the rupee will come under profound pressure, leading to a remarkable depreciation in a short period of time.

The general population will be burdened with rising prices, a stagnant economy, and a decline in real wages. This will not be something new, for the economy has witnessed similar crises prior to each of the previous ten bailouts by the IMF.

Economists inside and outside Pakistan have written and spoken about this issue at length, and it does not take a doctorate in economics to recognize the challenges facing Pakistan’s economy. The government has taken some measures to attract investment into Pakistan, with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor being a cornerstone of the strategy. The failure, however, lies in not taking measures to prevent crises that could engulf the economy in the medium term.

The continued rise in imports and declining exports have been at the heart of every balance of payments crisis the country has seen. Given Pakistan’s dependence on foreign oil, rising oil prices play a central role in these crises. Experts have laid out policy measures to eliminate the structural inefficiencies plaguing the economy and enhance the country’s abilsity to build foreign exchange reserves. Without a long-term strategic vision that seeks to convert nascent recoveries into a sustained period of economic growth, Pakistan will continue to go from one crisis to another and continue to rely on the IMF. n

Uzair Younus is an analyst at Albright Stonebridge Group and can be reached at uzairmyounus@gmail.com