Note: This extract is from the author’s coming autobiography titled Not The Whole Truth: My Life and Times.

Click here for the second part

In December 1960 my mother went to India to meet her parents. The partition had deprived her of their sight for such a long time that this was the biggest treat she could hope for. Ahmad and Tayayba accompanied her while I and Anwar Bhai remained home. Abba cooked a cauldron of egg pudding (ande ka halwa) and another one of carrot (gajar ka halwa) as these were the distinctive delicacies of our house. I spent my mornings making aircrafts of wood and playing with my friends in the evenings. My result of 4th Standard was declared and I stood first in the class. I remember how thrilled I was to hear my name called out in the huge, yellow, well-lighted dining hall by a priest. Hardly believing my ears I walked in a daze and Father Scanlon frowned—he was attempting to smile actually-- as he handed me my prize—Hans Christian Anderson’s Fairy Tales. My mother would have kissed me and given me money for such a success but my father’s approval was more measured so I do not remember it. I do, however, remember coming to the conclusion that I had, though unwittingly, worked far too hard. Next time, I resolved privately, I would study less of the courses and aim at remaining somewhere in the middle of the class. This, in fact, is exactly what I did till my last year in school when once again I topped the class.

In those holidays, contrary to my overall philosophy of not doing what looked like work as much as possible, I decided to learn the correct pronunciation of Quranic Arabic. As mentioned before, I had never read the Quran Nazra (without understanding the Arabic words), so I decided to trick my father into making that as the excuse of getting him to teach me. My father, despite his obvious religiosity, must have also have a secret philosophy of avoiding anything like work so he was not over enthusiastic. I did, however, rope him in using the name of the sacred which, of course, he could not resist. He agreed to teach me in the evening for about half an hour. I thought I had learned the rudiments of pronunciation (qirat) which Abba taught very well, by the tenth sipara. Abba too was quite pleased to get me off his back. After that, except for a few dips into it here and there, I read the complete Quran with meanings and commentary, and that too several times in the bargain, when I wrote my book entitled Interpretations of Jihad in South Asia: an Intellectual History (2018) much later.

We PMA boys were rather more innocent about sexual or romantic matters than our contemporaries elsewhere. Or, at least my closest friends were. As it happened, the girls who were our playmates were pretty. Reeno was a fair and spirited beauty who could be bold and saucy at times. She was the heartthrob of many boys later but none of my friends dared say a word to her about such matters. Kuku, her sister, was an attractive girl who grew up into the kind of beauty which is called olive-complexioned or wheatish. And Shala, the prettiest one, was a delicate fair-complexioned girl who also had many secret admirers. However, I, Javed Athar, Tariq Ahsan, Khalid Chum and Shaheen were so shy or decent or puritanical or cowardly that we never had anything like a romantic interlude, let alone an affair, with anyone of them. The nearest I came to one is as follows. Once near a thicket of a rose hedge a girl called Mushsho stopped me and asked me whether Kuku was my girlfriend and I loved her. I went hot in the face and said ‘No’ peremptorily and ran away with my cheeks burning and hair running riot in the wind. This must be when I was only ten or maybe eleven years old. This rebuff, however unintended and however regretted later in life, might have offended Kuku. However, she never showed it. Indeed, not only did she play, as did all of them, with me but also even hauled up my books when I was climbing the military trucks which brought us home from our schools. Quite paradoxically, despite this public display of partiality she never talked to me alone or in private. Once her sister Reeno gave me a lemon plucked from a tree in the PMA Officers Mess and a crooked stick for no apparent reason. That night I shifted my affection, or rather a mushy feeling shared only with the lemon and the stick, to her. This lasted about a week or so but, again, I never uttered a word of this to anybody—least of all to Reeno herself. Because of Kuku’s helping me with my books occasionally I was supposed to be in some kind of a relationship with her. This rumour I did not contradict as I was fourteen then and my days of running away from girls were over. However, my days of pursuing them had, unfortunately, not arrived—they never did, actually. The proof of this was that one day I was told by Shaheen after much blushing and trepidation, that he rather fancied Kuku. Why I was chosen for this confidence was because of the rumour of my being somehow involved with her. I told him enthusiastically to go ahead and to declare his love. This was too much for Shaheen who preferred, like me, to talk but did not actually do anything. I think now that if the girls knew in what cavalier way I shifted loyalties they would have hounded me out of polite society. The fact is that there were no actual loyalties to be shifted but talk about them was something macho by the time I was fourteen.

Thus, despite no action and no serious commitment at all, there was some talk between us boys about the girls who were our friends and playmates. The only one who never did talk about them was Tariq Ahsan who, if he overheard us, gravely admonished us on the grounds that they were sisters having grown up and played with us. But after this puritanical admonition, he giggled and beaming with delight, did participate in the banter so long as it was at our expense. At that time the hypocrisy of the scapegrace quite escaped me but now I tease him about it in our infrequent talks on the phone since he lives in Canada. Our talk about girls, despite what Tariq had to say about it, was just innocent banter and we took good care that the girls never found out about it. I and Javed Athar mentioned Shala with awed admiration. To hide her identity, we called her ‘shatack’ and then, to put curious people off the scent, ‘brown buffalo’ and its Urdu equivalent bhuri bhaens. For some such reason of secrecy Reeno was called Pandit Nehru but that was later and by boys who had joined us after our friends the Rafi children had departed. These boys were older and far less tongue-tied than us. Our ‘secret’ talk was nothing more than reporting where we saw someone last. There was nothing more than this and yet Tariq Ahsan, when he heard of the secret names I had given to Shala, called every gift of mine to her—these were just books for review for her husband Denis Matringe--‘ghosts’.

Even as late as 1997 when I was a married man with children—he teased me about ‘ghosts’. In this case I had presented my book Poems of Adolescence (1979) to Shala. Tariq Ahsan pounced upon this incident with unholy glee. He called it a case of ‘ghosts’. I confessed to nostalgia but he would not relent.

‘Most of the books were actually for Denis who reviews them in French journals’, I explained.

‘But this one is about your poems so it is not for him’, he said chortling with glee.

‘Well, yes. But she actually reads my books so this one is for being read’, I said.

‘As if I don’t read books. I burn them or something’, he countered.

‘Tariq, don’t you be silly. I give you every book if you are here but what can one do if you live in Canada. In any case you were among the first who got this book of poems’. He merely laughed. Tariq’s innocent raillery did not go beyond this.

In fact, I do not remember having actually talked to Shala in PMA when we were children. There was, even at age fourteen, a gender segregation in place though we did play, ride and go for a hike up the mountains now and then. Later this segregation got stricter and when Kuku was in college, she looked through me as did I. It is another matter that I, acutely regretting the time I had run away from her, always sneaked up to the hedge from where she was visible when she got down from the bus and walked home. She was seventeen then and I eighteen or so and she had become a very attractive girl but there was no question of talking to her now that we were both teenagers. At that time, I believed that none of the girls, and least of all Shala, noticed anything I did and the truth was that I did nothing to impress any of them. That was not on my mind at all.

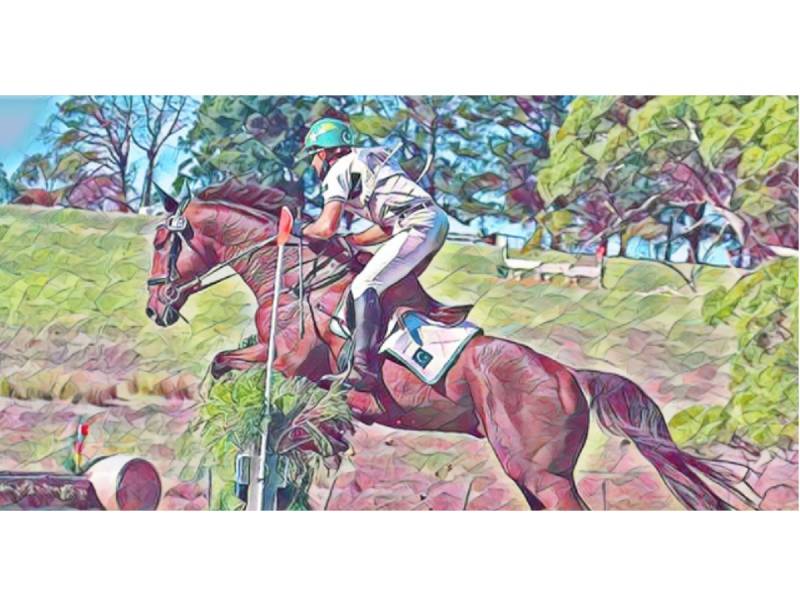

Years afterwards I found out that Shala had noticed and even admired my horsemanship. This happened when I visited her dying mother in the Naval hospital in Islamabad in 1998. I believe her mother might have had lapses of memory since Shala said to her mother by way of introducing me:

‘Mummy, look who has come to see you. Tariq. Do you remember him. He was such a good rider. Really outstanding he was’.

Auntie Rafi, though weak and faint, turned to her with some indignation. ‘Well, of course I know Tariq. He came to see me when you were still in France’.

Shala murmured to me that she did it as her mother sometimes forgot people. ‘Well’, I countered ‘Not those who visited her as she says. And, by the way, I did not know you noticed my riding in those days since you hardly ever talked about it then. Now you mention it, fifty years too late’. She laughed and kept quiet.

So, despite much talk about girls, none of us had girlfriends. The only one of our group who did boast about having girlfriends, and teddy girls to boot whose shirts were so tight that they came apart, was Gulzar Rana. But these hypothetical beings were in Lahore so in PMA Rana could only say we were wimps but not prove himself to be any different except in somewhat more uninhibited conversation than the rest of us. Even this loose talk led to a row between him and Shaheen which, I vaguely gathered, was basically about Shala. I was instinctively on Shaheen’s side though I did not know what, if anything at all, had happened. Fortunately, the actual fight did not take place and Rana made his peace.

The sixties were the time of the ‘teddy’ fashion. The new one paisa coin, small and shining, was smaller than the old paisa so it was called ‘teddy paisa’. Young people wore tight clothes and the boys wore pointed shoes. All were called ‘teddy’. There were all kinds of lascivious jokes about ‘teddy girls’ and Rana brought anecdotes—apocryphal no doubt—of how he was always present when one with particularly tight shirt or jeans got almost nude since the clothes burst at the seams. I pointed out to him that jeans do not get torn and shirts, even if they do, reveal nothing interesting. For my pains Rana gave me a scorching look, called me a village yokel, and raucously narrated a few more risqué stories which, however, nobody believed. Such things never happened in PMA, of course, though we too wore as tight clothes as the tailors and the papas allowed.

Our menu for entertainment, apart from the sports, was watching movies. I enjoyed both Urdu and English movies though I never bothered to remember the actors’ names. Indeed, when people talked of films with the names of actors, singers or directors I was nearly as blank as I was when they talked of cricketers. In time, however, I learned the names of some film actors but I am still unaware of the names of T.V. actors. The children’s show was on Sundays but I and Rana sneaked into ‘Come September’, supposed to be for adults only, into the room where they put the reels on the machines to screen the movie. We also loved music and listened to romantic Urdu songs—‘abhi na jao chhor kar’ (do not go leaving me yet) and ‘mujh ko apne gale laga lo’ (press me to your heart) were my favourites— and I often listened to them with Rana in his house. In time, however, Shaheen also acquainted me with English songs. Once again, I generally did not know the names of singers except Lata and the Beetles nor was I interested in names. There was no dancing at all where I lived though I knew that people danced in big cities and also on marriages. One evening, however, Shaheen introduced me to live dancing. He took me to his house and closed the drawing room with a conspiratorial air. Then he put some English record on and started gyrating his body. This, I was told, was a new dance called ‘twist’ and was so ultra-modern a phenomenon that I was given a vow of silence—a vow I have broken only now—that it was to be kept as a solemn secret.

Eids were wonderful occasions. The Eid-ul-Fitr, which Ammi called Chhoti Eid (Eid minor) came after a month of fasting (Ramazan). My parents fasted and I too fasted except on Tuesdays which, I declared, were my ‘holy days’. The reason was that I wanted to build up my strength for the riding day which was Wednesday. The other riding day, Saturday, came before Sunday so one did not have to go to school at least. As for the riding day itself, I did fast that day. It was more macho to declare one was fasting than otherwise. After our cook Baba, and even when he was there, Ammi worked very hard to provide delicacies on the table. There was the iftar with samosas, pakaoras (fritters) and other delicacies. Then there was a milk pudding made out of finely grounded wheat (suji ki kheer), fried thin loaves of bread (puris) and all sorts of kebabs, koftas (meat balls in curry), pasandas (steak cooked with condiments and yoghurt) and other meat dishes. On Eids we even ventured to Abbottabad to watch a movie there. I remember how Shahrukh came to my house to lure me to accompany him and some others on the Eid of 1963 to Abbottabad. I was electrified, jumped up and ran out of the house and we caught the PMA bus to the city. This trip is memorable since I bought my first diary that day and used to write it though not every day. This became a habit and I have diaries of all years till 1968 after which I left off writing them. We also bought comics on Eids and had a lot of fun.

The winter of 1963 was terribly cold and there was a blizzard which lasted several days leaving about three feet of snow on the ground. We enjoyed ourselves very much indeed playing with it all day and burying milk into it at night which we ate as ice cream. Soon Shaheen went away since his father had been appointed president Ayub’s military secretary in Rawalpindi. I had lost some excellent friends and was sad. Soon, however, Brigadier Sultan Mohammad was posted as commandant and I made friends with his son Mahmood Sultan or Salty. He had a younger brother, Maqsood, and a sister Feroza. Maqsood ran around with the younger kids, such as my brother Ahmad, but Feroza kept herself to the girls who were now completely segregated being teenagers.

This was also the year of the elections. Ayub Khan and Miss Fatima Jinnah were the presidential candidates and there was much excitement. My father was anti-Ayub since the Jamat-i-Islami was anti-Ayub. He said Ayub was not Islamic and corrupt to boot. My mother liked Ayub because, she declared, ‘he was so handsome’. I had no opinion at all. Tariq Ahsan, the most well-informed among us, was anti-Ayub. He told us about democratic values and the drawbacks of military rule. These were new ideas for us and I argued heatedly with Tariq Ahsan that there was nothing wrong with Ayub’s rule as it had made us prosperous. Gradually, however, I started understanding his point of view and accepting his liberal ideas.

In 1964 we moved to yet another full hut which was adjacent to Uncle Naseer Uddin’s hut. This was more beautiful than our previous huts. It too had large, well-maintained lawns around it, and a few fruit trees. Jetho moved to a newly constructed bungalow but the lawns were much smaller than those of his old hut so there was no room to play. We kept meeting in the park but no longer played the old games we were used to. However, we still went for riding, swimming and mountaineering and I began a long story of adventures in a fictional war which threatened never to end. I got a bicycle, which we called a bike, made by the Batala company in 1965. My mother had regretted that I never told my father that I too wanted a bike when she was in India. My friends—Khalid, Shaheen, Tarsan (as Tariq Ahsan was called), Reeno and Kuku—all had bikes. However, some kind of shyness or the feeling that my father would not buy it for me, prevented me from asking him which was a constant source of regret and pain for my mother. So, when I did get a bike, I made the best of it. The first ride on it was with Ahmad and he tells me that we fell many times but nobody bothered about the injuries.