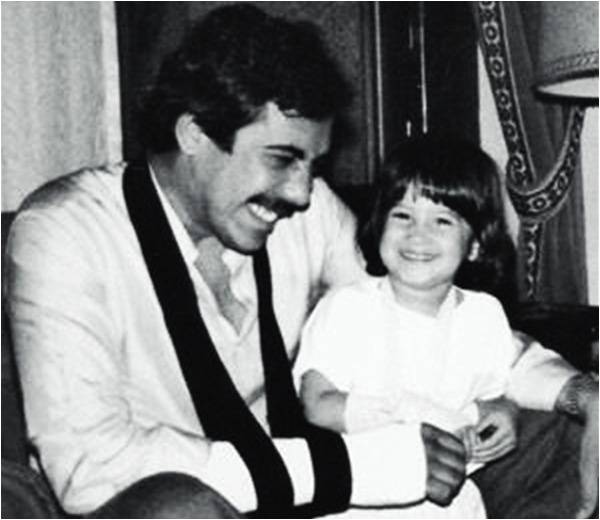

Murtaza Bhutto and his daughter Fatima smile in this undated photograph, taken likely in 1986.

The following excerpt from her memoir, Songs of Blood and Sword, is about her father’s assassination a decade later, in 1996.

“While the shooting lasted, five minutes at the very least, and with no pause in the crack of the bullets, Zulfi huddled against me. I hugged him and pushed his face into my arms and chest, as if I could protect him from the sound. ‘Where’s Mummy?’ I didn’t know. I hoped she was still in the kitchen, it faced the other side of the house and the gunfire wouldn’t have been as close to her as it was to us.

“We waited for a few seconds. It had stopped. I told Zulfi to wait for me; I was going to check where our mother was. As I stood up, Mummy burst into the bedroom screaming. ‘We’re here!’ I yelled and she threw open the door to the dressing room instantly pulling me into her arms and pulling Zulfi up off the floor. ‘Let’s go to the drawing room,’ Mummy said, breathing quickly. It too had no windows and was not as confined as the yellow dressing room we had been hiding in.

“We sat in the drawing room for close to half an hour, waiting. The shooting had stopped and we asked our chowkidar, our gatekeeper, to check outside and tell us what had happened. The area was thronged with police, he said. They wouldn’t let him out of the house. ‘There’s been a robbery, there are dacoits outside,’ the police told the chowkidar. ‘Stay inside until it’s safe.’

“Mummy sat on the sofa in the drawing room with her hands to her face. I paced up and down the room. There were no mobile phones in Pakistan then. They had been banned by the democratic government (who managed to keep a few for themselves before closing down the market for the rest of the country). We had no way of reaching Papa and no choice but to wait for him, patiently.”

The following excerpt from her memoir, Songs of Blood and Sword, is about her father’s assassination a decade later, in 1996.

“While the shooting lasted, five minutes at the very least, and with no pause in the crack of the bullets, Zulfi huddled against me. I hugged him and pushed his face into my arms and chest, as if I could protect him from the sound. ‘Where’s Mummy?’ I didn’t know. I hoped she was still in the kitchen, it faced the other side of the house and the gunfire wouldn’t have been as close to her as it was to us.

“We waited for a few seconds. It had stopped. I told Zulfi to wait for me; I was going to check where our mother was. As I stood up, Mummy burst into the bedroom screaming. ‘We’re here!’ I yelled and she threw open the door to the dressing room instantly pulling me into her arms and pulling Zulfi up off the floor. ‘Let’s go to the drawing room,’ Mummy said, breathing quickly. It too had no windows and was not as confined as the yellow dressing room we had been hiding in.

“We sat in the drawing room for close to half an hour, waiting. The shooting had stopped and we asked our chowkidar, our gatekeeper, to check outside and tell us what had happened. The area was thronged with police, he said. They wouldn’t let him out of the house. ‘There’s been a robbery, there are dacoits outside,’ the police told the chowkidar. ‘Stay inside until it’s safe.’

“Mummy sat on the sofa in the drawing room with her hands to her face. I paced up and down the room. There were no mobile phones in Pakistan then. They had been banned by the democratic government (who managed to keep a few for themselves before closing down the market for the rest of the country). We had no way of reaching Papa and no choice but to wait for him, patiently.”