His life was to be played out in Makhachkala, but fate ultimately landed him in Lahore, in a country which at the time of his entry was almost 3 years old. It was here that his icon would become nationally famous. Minar-e-Pakistan, also known previously as Pakistan Day Memorial, stands tall in Minto Park.

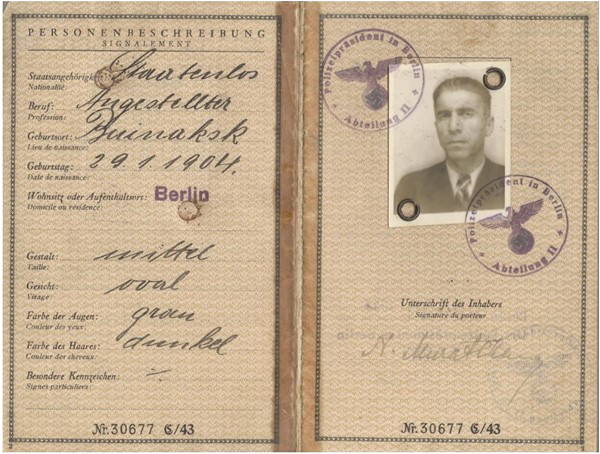

Nasreddin Murat-Khan was born in 1904 in Buynaksk, which is today in the Republic of Dagestan, part of the Russian Federation. The eldest of three, he attended Cadet School in Buynaksk from 1911-1920, and joined St. Petersburg State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering in 1925. He graduated with degrees in architecture, civil engineering and town planning five years later.

His professional career from 1931 to 1942 gave him experience as a civil engineer, architect and town planner in Derbent, Makhachkala, Pijatgorak, Woroschilowsk and Stavropol. Becoming a fellow of the Institute of Architects in 1937, he also was President of the North Caucasus Branch of the Soviet Architects Association as well as Chief Architect and Chief Engineer of the Technical Consultation Trust Dagestan and the North Caucasian Project Trust.

The war changed much for many people, and somewhere in 1943, Murat-Khan was forced to make probably the most difficult decision of his life with the consent of his family, a decision which meant saving his life. Leaving behind family and country, he fled when the German army retreated from the USSR and after a long journey, reached Berlin in 1944. Thereafter he was placed in the UNRRA camp in Mittenwald, Germany, working as an engineer. His life was to take a new twist here, unknown to him or to Hamida Akmut (Austrian mother, Pakistani father). A third-year student of medicine at the University of Vienna, she was to join her parents in Turkey after Soviet forces entered Vienna in 1945. Her journey made a stop in the same UNRRA camp in Mittenwald as Murat-Khan, where she worked in the medical field until her planned repatriation to Turkey could be completed. They met, and within six weeks, decided to marry in 1946.

The war changed much for many people, and somewhere in 1943, Murat-Khan was forced to make probably the most difficult decision of his life with the consent of his family, a decision which meant saving his life. Leaving behind family and country, he fled when the German army retreated from the USSR and after a long journey, reached Berlin in 1944. Thereafter he was placed in the UNRRA camp in Mittenwald, Germany, working as an engineer. His life was to take a new twist here, unknown to him or to Hamida Akmut (Austrian mother, Pakistani father). A third-year student of medicine at the University of Vienna, she was to join her parents in Turkey after Soviet forces entered Vienna in 1945. Her journey made a stop in the same UNRRA camp in Mittenwald as Murat-Khan, where she worked in the medical field until her planned repatriation to Turkey could be completed. They met, and within six weeks, decided to marry in 1946.

Because the UNRRA camps were shutting down, a decision had to be made as to where to go by 1949. Hamida’s parents had returned to Pakistan by then. Perhaps because there was family there (as he had no communication whatsoever with his), they arrived by ship in April 1950. His first job was as a Garrison Engineer at Wah Ordinance Factory where his father-in-law Dr. Hafiz Akmut was stationed. He then moved to Lahore in 1951 where he joined the Public Work s Department (PWD). He later became Consulting Architect to the PWD. In 1958, he gave up this post in order to start his own firm (Illeri Murat Khan & Associates), which was launched in 1959.

s Department (PWD). He later became Consulting Architect to the PWD. In 1958, he gave up this post in order to start his own firm (Illeri Murat Khan & Associates), which was launched in 1959.

In his eleven years of practice, numerous projects can be credited to his name – Fortress Stadium, Nishtar Medical College and Hospital, Gaddafi Stadium, WAPDA housing colonies, FCC Auditorium, Services Hospital, flats, over 80 residences, parks, educational institutions and mosques. But his biggest achievement, his legacy, and his pride was – and is – Minar-e-Pakistan. None of his family, including Murat-Khan himself, expected it to become a national icon. And while recognition for his huge contribution as the architect, engineer, and financial contributor (he never charged for the design nor for the supervision) did not come in his lifetime, it is now there for all to see. He was awarded the Tamgha-e-Imtiaz in 1963, a civilian award given for excellence.

In a letter he wrote of having lost what was most dear to his heart: his homeland and his family. It was a painful burden he carried throughout his 66-year life – but a burden lightened by his wife who always stood by him. As fate brought him here, fate also gave him a miraculous opportunity to meet his younger sister who had settled in Iran several years before his death in October 1970.

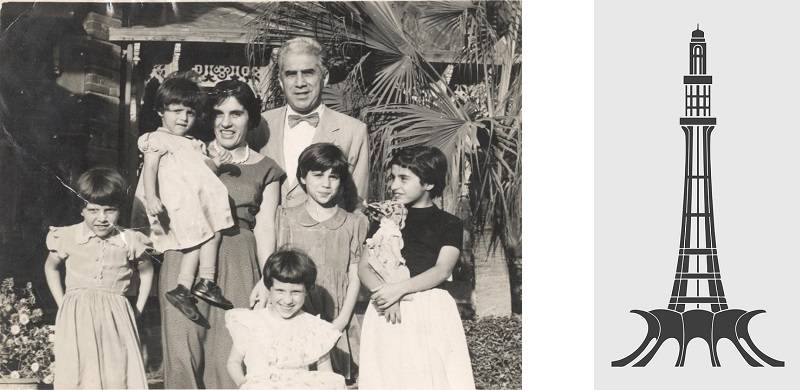

About 5'10” tall, he had wavy white hair and a booming voice easily heard when angered or aggravated. His wife had a quiet yet commanding voice.

As a father, he continued to encourage his five daughters to do their best, always expecting them to respect their mother, elders and the country they were living in. As a friend, he continued to uphold his principles while sharing his life with others through his sense of humour, love of music, encouragement and willingness to teach others, inviting friends and family over, and creating a new life in a new country while retaining the good flavours of cultures he had assimilated.

Nasreddin Murat-Khan was born in 1904 in Buynaksk, which is today in the Republic of Dagestan, part of the Russian Federation. The eldest of three, he attended Cadet School in Buynaksk from 1911-1920, and joined St. Petersburg State University of Architecture and Civil Engineering in 1925. He graduated with degrees in architecture, civil engineering and town planning five years later.

His professional career from 1931 to 1942 gave him experience as a civil engineer, architect and town planner in Derbent, Makhachkala, Pijatgorak, Woroschilowsk and Stavropol. Becoming a fellow of the Institute of Architects in 1937, he also was President of the North Caucasus Branch of the Soviet Architects Association as well as Chief Architect and Chief Engineer of the Technical Consultation Trust Dagestan and the North Caucasian Project Trust.

The war changed much for many people, and somewhere in 1943, Murat-Khan was forced to make probably the most difficult decision of his life with the consent of his family, a decision which meant saving his life. Leaving behind family and country, he fled when the German army retreated from the USSR and after a long journey, reached Berlin in 1944. Thereafter he was placed in the UNRRA camp in Mittenwald, Germany, working as an engineer. His life was to take a new twist here, unknown to him or to Hamida Akmut (Austrian mother, Pakistani father). A third-year student of medicine at the University of Vienna, she was to join her parents in Turkey after Soviet forces entered Vienna in 1945. Her journey made a stop in the same UNRRA camp in Mittenwald as Murat-Khan, where she worked in the medical field until her planned repatriation to Turkey could be completed. They met, and within six weeks, decided to marry in 1946.

The war changed much for many people, and somewhere in 1943, Murat-Khan was forced to make probably the most difficult decision of his life with the consent of his family, a decision which meant saving his life. Leaving behind family and country, he fled when the German army retreated from the USSR and after a long journey, reached Berlin in 1944. Thereafter he was placed in the UNRRA camp in Mittenwald, Germany, working as an engineer. His life was to take a new twist here, unknown to him or to Hamida Akmut (Austrian mother, Pakistani father). A third-year student of medicine at the University of Vienna, she was to join her parents in Turkey after Soviet forces entered Vienna in 1945. Her journey made a stop in the same UNRRA camp in Mittenwald as Murat-Khan, where she worked in the medical field until her planned repatriation to Turkey could be completed. They met, and within six weeks, decided to marry in 1946.Numerous projects can be credited to his name – Fortress Stadium, Nishtar Medical College and Hospital, Gaddafi Stadium, WAPDA housing colonies, FCC Auditorium, Services Hospital, flats, over 80 residences, parks, educational institutions and mosques. But his biggest achievement, his legacy and his pride was – and is – Minar-e-Pakistan. None of his family, including Murat-Khan himself, expected it to become a national icon

Because the UNRRA camps were shutting down, a decision had to be made as to where to go by 1949. Hamida’s parents had returned to Pakistan by then. Perhaps because there was family there (as he had no communication whatsoever with his), they arrived by ship in April 1950. His first job was as a Garrison Engineer at Wah Ordinance Factory where his father-in-law Dr. Hafiz Akmut was stationed. He then moved to Lahore in 1951 where he joined the Public Work

s Department (PWD). He later became Consulting Architect to the PWD. In 1958, he gave up this post in order to start his own firm (Illeri Murat Khan & Associates), which was launched in 1959.

s Department (PWD). He later became Consulting Architect to the PWD. In 1958, he gave up this post in order to start his own firm (Illeri Murat Khan & Associates), which was launched in 1959.In his eleven years of practice, numerous projects can be credited to his name – Fortress Stadium, Nishtar Medical College and Hospital, Gaddafi Stadium, WAPDA housing colonies, FCC Auditorium, Services Hospital, flats, over 80 residences, parks, educational institutions and mosques. But his biggest achievement, his legacy, and his pride was – and is – Minar-e-Pakistan. None of his family, including Murat-Khan himself, expected it to become a national icon. And while recognition for his huge contribution as the architect, engineer, and financial contributor (he never charged for the design nor for the supervision) did not come in his lifetime, it is now there for all to see. He was awarded the Tamgha-e-Imtiaz in 1963, a civilian award given for excellence.

In a letter he wrote of having lost what was most dear to his heart: his homeland and his family. It was a painful burden he carried throughout his 66-year life – but a burden lightened by his wife who always stood by him. As fate brought him here, fate also gave him a miraculous opportunity to meet his younger sister who had settled in Iran several years before his death in October 1970.

About 5'10” tall, he had wavy white hair and a booming voice easily heard when angered or aggravated. His wife had a quiet yet commanding voice.

As a father, he continued to encourage his five daughters to do their best, always expecting them to respect their mother, elders and the country they were living in. As a friend, he continued to uphold his principles while sharing his life with others through his sense of humour, love of music, encouragement and willingness to teach others, inviting friends and family over, and creating a new life in a new country while retaining the good flavours of cultures he had assimilated.