What distinguishes heresy from faith, apostasy from honest belief, infidelity from religious ardour, and blasphemy from true awakening? How does it feel to undergo an intense mystical experience or a deep spiritual crisis that persuades one to cast off long-held beliefs and relinquish the comforting solace of home and hearth? Is the capacity to look beyond what is invisible to all, to be extraordinary and deeply insightful, a blessing or a curse? What is this passionate, overwhelming desire that some of us have always had to gaze upon Divinity - face to face?

The great triumph of Jamila Hashmi's neglected novel is the passionate lyricism and deep poetic sensibility with which she captures the life, times and mystical quest of the great 19th-century Persian poet Qurat-ul-Ain Tahira. This is a book to be savoured for its masterly use of language as well as intricate assessment of the religious, political, theological and spiritual movements and contestations of Tahira's epoch. Tahira is a poet of great and distinctive beauty and pathos and time and again her haunting Persian verse is skilfully employed by Hashmi to weave the story of her early life, her spiritual anguish, her mystical experiments, and then her pivotal association with the 19th century religion Babism. Babism drew on the Shaykhism movement in 19th century Iran and was founded by a young and charismatic merchant called Ali Muhammad from Shiraz who claimed prophethood. As in her magnum opus Dasht-e-Soos on the life and times of Mansoor Hallaj, Hashmi displays astounding knowledge of Islamic history and the various sects, fissures, schisms and contestations over the centuries. Her approach to Babism is not dogmatically castigatory; instead, she treats it as an outcome of the growing social discontent with the state of affairs in mid-nineteenth century Iran, a desire to claim religious ascendence by Persians, and the intense speculation about the arrival of Imam Mehdi that was rife at the times. Her literary virtuosity, penchant for history and masterly capturing of complex and controversial historical figures make Hashmi one of our foremost historical fiction writers.

Wahdat-ul-Wajood or unity of existence is the underlying desire that Qurat-ul-Ain Tahira harbours as indeed also an overwhelming curiosity to discover what lies beyond the veils that impede human capacity to look into the future and beyond the apparent. The obsession to gaze into the deepest secrets of creation. And indeed, at the Creator. Are we also part of Divinity, no matter how inconsequential and minuscule? Can we aspire to Divine characteristics ourselves? Can we become part of the Divine? What is our true potential? What does it mean to lose ourselves in, to extinguish ourselves, in order to become part of the Divine - what is Fana? Both the mundaneness of growing up in a traditional though educated clerical family and a monotonous marital existence and the staid theological and religious discourses of her time led Tahira to new mystical journeys. She first followed the teachings of Sayyid Kazim Rashti, a successor of Sheikh Ahmad al Ahsai - both Shia scholars - one of whose main preoccupations was the prediction of the coming of and explanation of the way to recognize of the Mahdi and the Masih. Post his death some of his followers became Babis and later split into other factions - the Bahai faith also grew out of Babism. Unable to meet Sayyid Kazim Rashti before he passed away, though in correspondence with him, Qurat-ul-Ain Tahira was strongly drawn to Babi thought - a messianic movement that was a break from Shia Islam and categorized as a new religion - and spent the rest of her life as one of its integral figures, polemicists and evangelists.

Hashmi's prose is at times steeped in symbolism and is deliberately suggestive and ambiguous - given both that it deals with an era, religion and movement that is still somewhat mired in mystery, and due to the complexity, controversy and unknowability of many of the mystical and spiritual ideas that her protagonist grapples with. What she does brilliantly is to capture the anguish, the thirst and the zeal that must have overwhelmed and tormented Qurat-ul-Ain Tahira in her endeavor to look past the curtains and gaze at what is not known and is perhaps even unknowable. Extraordinary people who over the centuries have come up with new ideas, brought about revolutions, or have founded religions, have always had to face strident scrutiny, criticism and persecution. Tahira's lot is no different. Hashmi tells her tale with great feeling and sentiment.

Throughout the novel Hashmi dwells on the various contestations and schisms within Islam, employing metaphors from the great tragedy of Karbala, and expounding on both the dynastic struggles and power grabs in its history, the havoc wreaked on the Islamic world by Mongols and other invaders, as well as the various 'fasads' and 'fitnas' that have emerged in Muslim polity through the years. Her treatment of Tahira's quest and indeed of Babism (from the Arabic 'Bab' or Gate) however, is neither as a sect or movement spawned and driven by avarice, ambition, opportunism or madness, nor necessitated by political imperatives. In her rendition, it is a deep spiritual vacuum at the personal and societal level and perhaps also a felt desire on part of many that the times required a revival of the sharia - a new path ahead. Given how widespread and oft-discussed also was the expectation of the arrival of the Mehdi, it is arguable that Babism or something similar was bound to happen.

As Hashmi says in the novel: "A thousand years is a long time for a faith to face the test and to wait." The soil was moist and willing. In earlier centuries the great anxiety and anticipation about the anti-Christ and the second coming of Christ had also triggered major events in terms of new sects and religious movements. The zeal shown by Babists is similar to the zealotry of similar religious adherents in the past, including the Hashisheen. The founder of the faith Ali Muhammad 'Bab', and many of his followers faced brutal persecution by the Iranian army of the time and many including Ali 'Bab', Mulla Hussayn Bushrui (also known as the 'Bab-al-Bab'), Mohammad Ali Barforusi (also known as 'Qoddus'), and Tahira herself, were publicly executed, killed in battle, humiliated and slaughtered by a mob, or clandestinely killed, respectively.

Ultimately, what makes Hashmi’s novel a truly remarkable book and one of the outstanding novels in Urdu is its lyrical and thoughtful engagement - not many of our writers are both lyrical and thoughtful - with fundamental questions about human existence, our ability to ask deep questions, the enigma of our creation and our universe, and the courage and extraordinary insight, perseverance and will that emboldens those such as Qurat-ul-Ain Tahira to dismantle the given understanding of things and try and lift the veil. For a 19th century woman from a traditional Persian family to attempt this is all the more remarkable.

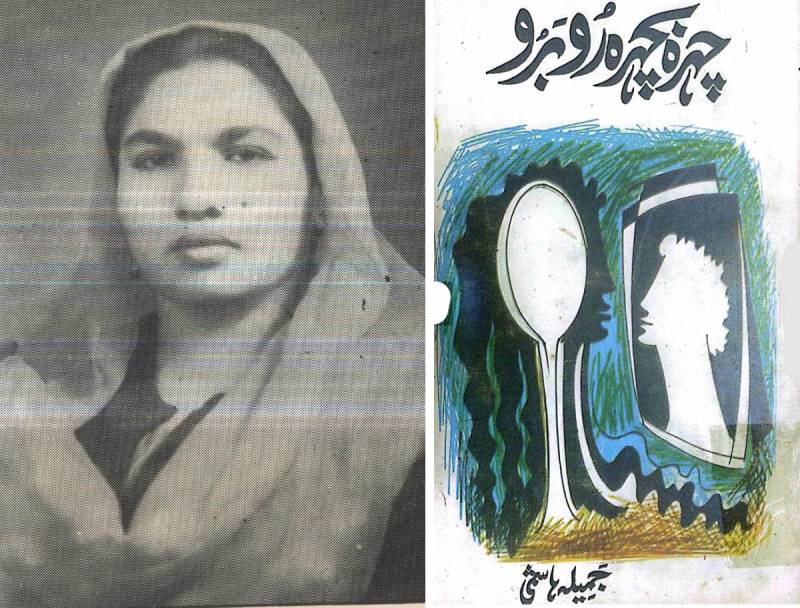

I have always thought that Jamila Hashmi is a wonderful but highly under-rated writer. In this novel and in Dasht-e-Soos she has gifted us two brilliant books set in lands that lie to our west and that are inspired by the troubled and troubling history of orthodoxy and actual or perceived heresy. She also offers much more that is steeped in the colours of our own land, including most notably Atish-e-Rafta and Rohi. Our copyright laws unfortunately ensure that between negligent successors and indifferent publishers truly great pieces of literature are very poorly treated. This is a horribly printed edition from 1979 which went out of print and the book was therefore unavailable for many years before a publisher finally reprinted it in 2022. The old edition has quite a few mistakes, is indecipherable at times due to the abysmal calligraphy, and is also missing words. It remains to be seen whether the current publisher has invested the requisite effort to address these blemishes.

Tahira's poetry of course also inspired Iqbal who was fascinated by the depth of Ishq and devotion that those like her and Hallaj displayed in pursuit of their self-exploration and search for answers. He includes her most famous verse as her voice or Qurat-ul-Ain Tahira ki Nawa/Kalam in his masterpiece Javed Nama. As even the opening lines reveal the poem is brilliant in its evocation and intensity of pursuit:

Gar ba-tu uft'dam nazar chehra ba-chehra, roo ba-roo

Sharah deham gham e tura nukta ba-nukta, moo ba-moo

Qurat-ul-Ain, Tahira or Tahireh, Janeb-e-Tahira, Zarrin Taj, Umm-e-Salma, the poetess of Qazvin - known for her rare physical beauty, a mystic, a cardinal figure of the Babi movement, an advocate of female emancipation, an evangelist, a polemicist, a scholar, a passionate seeker of the truth, and a poet of great lyricism and pathos - remains a highly enigmatic and inspiring figure of recent times. Chehra ba Chehra Roo ba Roo is a highly fitting tribute to her and one of the great novels of Urdu.