A sea of humans gathered for what appears to be a religious event portrayed on a sheet of paper or a glass may hold the gaze of the onlooker for a while – till a nonhuman creature towering above or lurking in the periphery is spotted, catching one by surprise.

This is perhaps how the work of Lahore-based artist Ghazi Sikander Mirza can be perceived especially if being viewed for the first time. Showcased at Artescape Gallery in Kohsar Market, Islamabad, the exhibit “Heavenly Bodies,” curated by Mahr Lak, portrays these details.

For those, however, who are familiar with Mirza's work, it does not take a long while to place his art in real-time as it happens – within the ninth and tenth Muharram annual procession or Juloos in Pakistan, and more so on the streets of Islampura, commonly known as Krishan Nagar.

Depiction of Muharram processions or religious gatherings for that matter has not been novel in Pakistan, especially because painting Zuljinaahs, or the misery faced by Imam Hussain and his aides has been a common theme in Shia traditions. But Mirza approaches the subject in his own unique way through both the choice of medium and the marriage of human and nonhuman in his art.

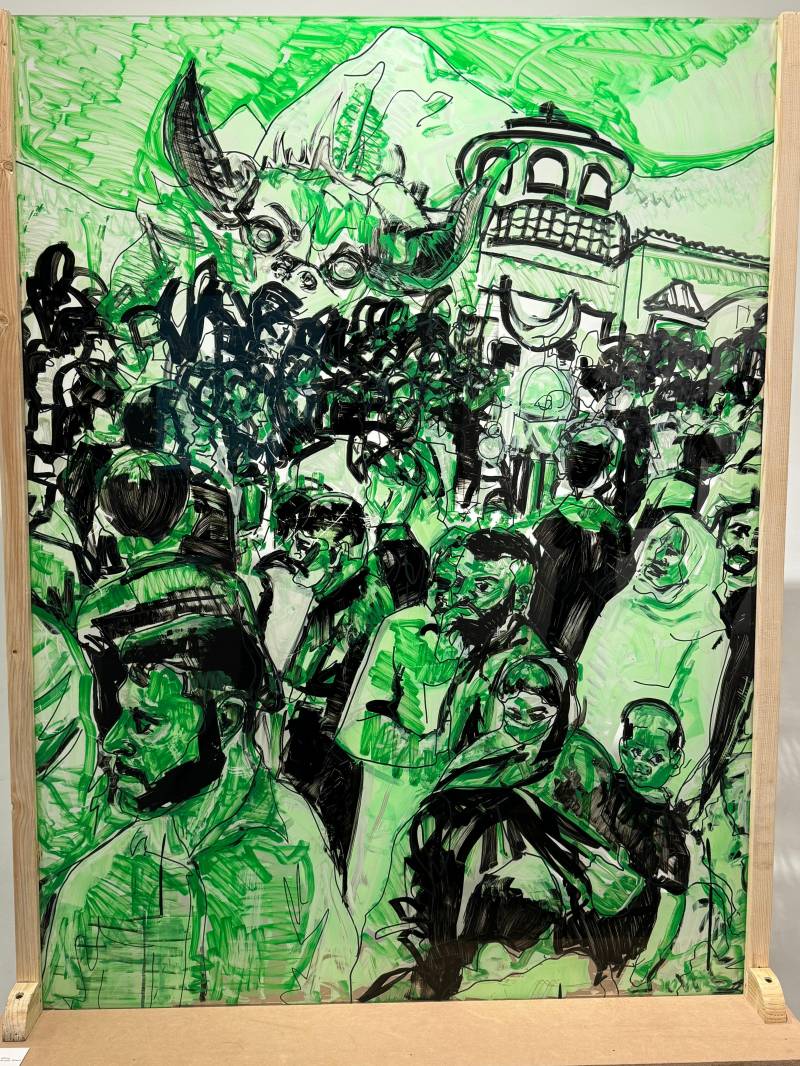

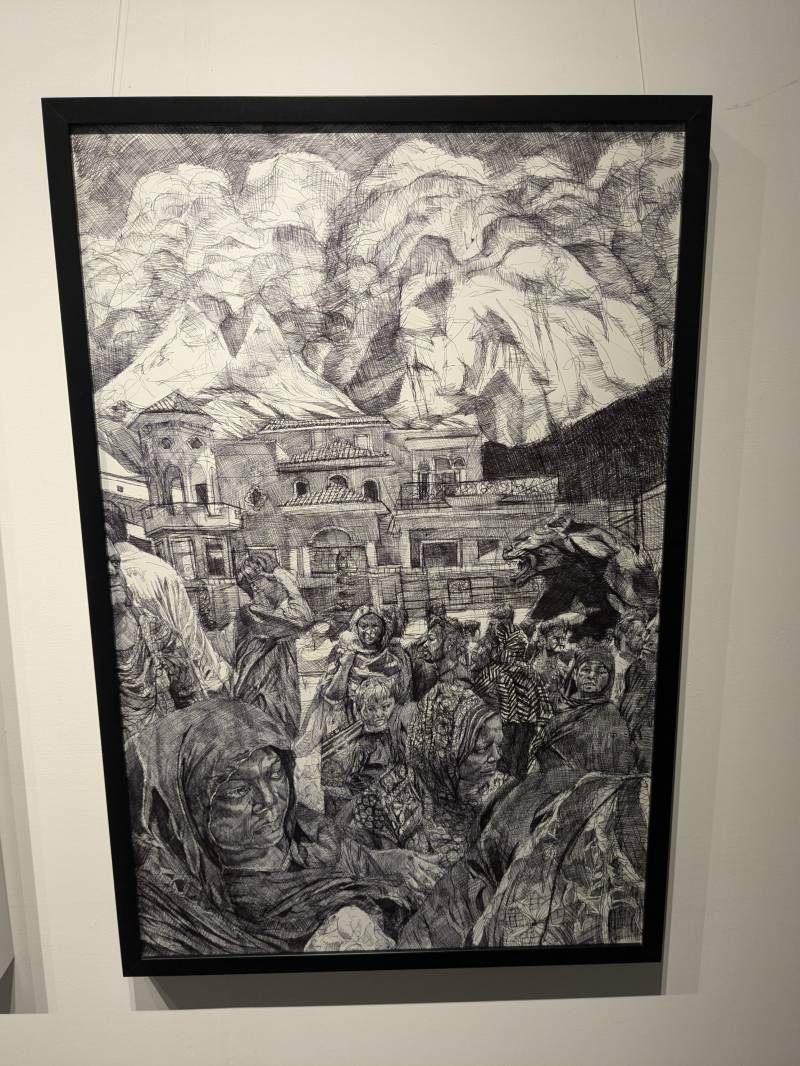

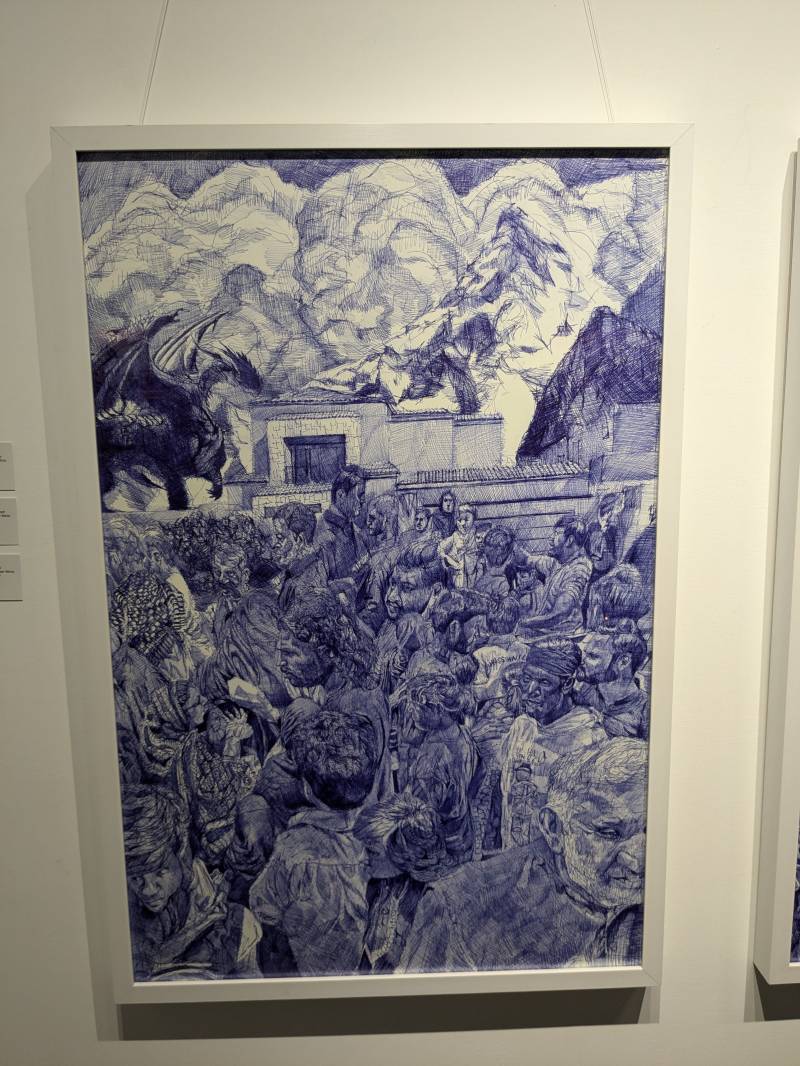

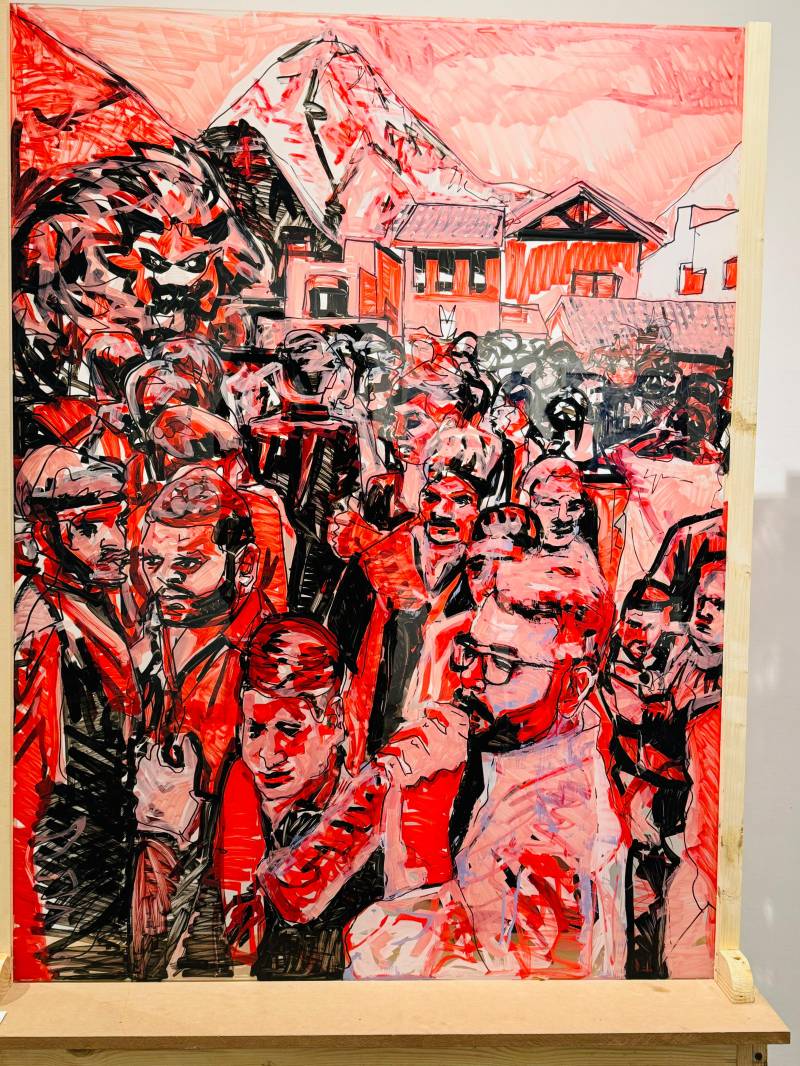

Mirza uses ballpoint, black or blue, to draw various scenes from the Juloos where the attendees are in motion, some are standing, some have their arms stretched either requesting from Sabeel or raising to do matam. He uses collages of photographs and his own memory to bring those moments to life, adding a colour or two through markers on acrylic.

Speaking about his work around religious rituals, Mirza recalls that as a part of a college assignment he was once asked to paint someone closest to his heart.

“I wanted to portray someone held in high reverence but could not due to obvious reasons. So then I gravitated towards the Juloos owing to the aesthetic of density, which I experienced yet again during the ninth Muharram and Ashura Juloos. For instance you are standing at the Sabeel, serving milk to the attendees while your family members are busy distributing food and other items to the crowds who keep on moving towards you, and there is a literal sea of humans, which presents a very dense, humanoid image.

Mirza’s art, although placed in the busy streets of urban Lahore, has mountain peaks and clouds as the background, which is an interesting juxtaposition for an architecturally rich city

One of the most humbling tenets of Juloos is how it presents everyone as one – blurring class, ethnicity bringing everyone on a level playing field. There are distortions as well which I like to experiment with,” he explains.

While looking at his work, the presence of nonhuman creatures, who can be dubbed as ‘beastly’ can invoke a sense of discomfort which can very soon also transform into curiosity as one wonders their placement leading to several questions. This aspect is intriguing because art is supposed to lead one there. The placement of these nonhuman is fascinating because they are activated, and do not hesitate in becoming part of the rituals. They are not passive, but at the same time cast no effect on the Juloos attendees signalling either the heightened grief or of course a zone where no one is barred and all are welcomed, in whichever form they may choose to appear in. Mirza leaves this interpretation open to the onlooker, and says that it is an amalgamation of the real and the mythical. The work does seem to embody the depiction of creatures in the western anthropomorphism as well.

The curator, Lak, finds the placement very intelligent: “There are so many faces and people and, because the work is monochromatic, he (Mirza) prefers using single shades. The creatures kind of blend into the people. It's not the first thing you see. It's one of the things you see in the paintings, so they don't really stand out until you really focus on them. Even then, they are convincing you that we are part of this world, that we belong here.”

Speaking more about Mirza’s work, Lak said that he first saw the work at Dominion Gallery because he does these massive murals on acrylic sheets: “It's very different in a way because he does tackle a very sensitive subject of religion and Ashura. But he does it in a way that it becomes relatable to a larger audience. What I personally find really fascinating is his ability to take such a humble pen and create something truly remarkable.”

Referring to the famous ballpoint pen, Mirza says that he uses a local Piano Crystal because the colour does not fade.

“My tutor used to have one and he would finish one pen fully before moving onto the next one and I think that really fascinated me. The sheets I have used are the 300g ones which I just got from Urdu Bazaar in Lahore,” he says.

Mirza’s art, although placed in the busy streets of urban Lahore, has mountain peaks and clouds as the background, which is an interesting juxtaposition for an architecturally rich city.

“Of course religious congregations are symbolic of the community but for me the sublime also stands out which I want to show through the mountains. The peak becomes a symbol, showing the presence of something bigger with grandeur. I could have also replicated the cityscape with the Bata shoe shop and frankly, I also tried that but it did not work for me so I decided to show let’s say a house with clouds emerging from behind which is more clear in the ballpoint ones,” he explains.

Commenting on the other pieces, which are in the hues of bright green, blue and pink, a departure from the solid ballpoint finish black and blue, Mirza feels that just like primary colours give birth to unlimited colours, and are thus omnipresent, the essence of Azaadari, commemoration of the grief of Karbala is the same and the choice of colours reflects this as well.