Knowing that Pakistan had made it to the 2009 T20 World Cup finals, I had bought cheap tickets to attend the big match at the Lords cricket ground with the hopes of seeing Pakistan close out the tournament with a bang. For reference: this match was against Sri Lanka; and I found myself in a noisy stand with hundreds of other euphoric Pakistanis cheering our team to an easy victory. It was not hard, amalgamating myself into the jubilant sea of green that spilled into the streets of London, reverberating with dhol, dhamaka and bhangra. Amidst the festive cacophony, one chant which stood out was the ‘Dil Dil Pakistan’ (henceforth: DDP), an indie pop song done by Pakistan’s very own Vital Signs in 1987.

Ironically, the song brought back two extremely distinct memories: Dil Dil Pakistan reverberating at the Australian cricket ground when Pakistan won the 1992 Cricket World Cup; and news of Pakistani hackers forcing airborne Indian pilots to listen to DDP. Occurrences like these underscore the emotive value of DDP – that (in due course) unassumingly, unknowingly and unofficially became Pakistan’s second national anthem.

Let’s momentarily take one step back.

DDP is a simple song: a low-budget amateur video shot in the very scenic Islamabad. The video features the four band members riding bikes, driving around in an open jeep and playing their instruments in parks. All of us would agree that DDP: with its with keyboards, synthesizers, and guitars had a very 80s feel; combined with its very patriotic lyrics, DDP strikes a major chord in Pakistanis’ hearts. Maybe this is why it shouldn’t come off as a surprise that the song once came off as the world’s third most favourite song in 2002 by a BBC World Services poll.

Recall that DDP was released during the times of dictator Ziaul Haq, whose regime orchestrated the Islamisation of Pakistan. The hallmark of his rule included fundamentalism, prohibition, militarization and censorship. This austere period ironically provided very fertile grounds for Pakistani popular culture to thrive – where Pakistan Television gave a platform to artists such as Nazia Hassan, Vital Signs and Hasan Jehangir. At the same time, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan exploded on to the international scene with his Urdu/Punjabi qawalli; he regularly performed to packed houses in auditoriums, political gatherings and celebrity weddings across the world. Pakistani dramas like Dhoop Kinare and Tanhaiyan were smuggled on pirated video cassettes across borders and were wildly popular with viewers for reasons we all know. Comedians like Umar Shareef and Moin Akhtar performed stage shows in the UAE; these performances can be said to be precursors to Kapil Sharma’s situational skits. And around the same time, Imran Khan was curating a world-beating cricket team with monstrously talented players like Wasim Akram, Waqar Younis and Inzamamul Haq.

This was the Pakistan that generations above mine remember and love.

Let’s now look across Pakistan’s borders – during the same time-period. Bollywood was facing a lull: releasing multi-starrers with subpar scripts and forgettable music. Indian cricket was transitioning. Javed Miandad’s last ball six off Chetan Sharma at Sharjah in 1986 was a thing of legends and Gavaskar’s swansong at his last test match against Pakistan at home in 1987 turned out to be a thrilling victory for Pakistan. Two years later Pakistan defeated the mighty West Indies in the final at New Delhi to clinch the Nehru Cup. Rare visuals of Lahore, Karachi and Islamabad showed smooth roads, broad avenues and organised urbanisation with imported cars and buses.

Now let’s trace the lives of two of the protagonists of DDP over the years; this discourse would reveal a lot about the trajectory of Pakistan’s contemporary politics.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was increased radicalisation and overt religiosity in Pakistan – where generals, pop culture icons and cricketers like Inzamamul Haq, Mushtaq Ahmed, Saeed Anwar and Mohammed Yousuf started growing beards and openly offered their namaz to demonstrate their piety. Post Zia’s mysterious death, there has been a constant musical chairs over the “throne” – with little (if any) regard for a steady national policy on the economy and strategic affairs. The rest, as they say, is history: beggaring the exchequer, weakening institutional autonomy and fueling political corruption.

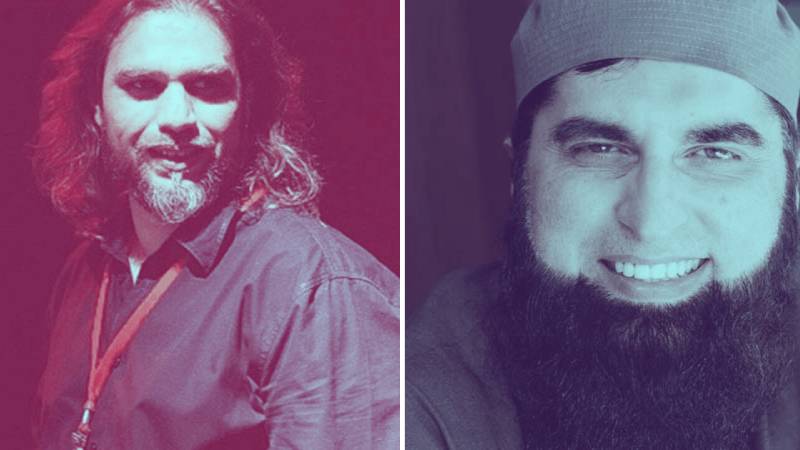

In the backdrop of this growing fundamentalism, Junaid Jamshed (the lead singer of Vital Signs) adopted a religious persona. He grew his beard long, shunned his heartthrob image, and later joined the Tablighi Jamaat: a puritan Deobandi group, that claims to be an apolitical organisation. Many Pakistanis say that the Tablighi Jamaat gives ideological impetus to most extremist / militant religious organisations in Pakistan, including the Taliban. Recall that Junaid Jamshed had also started his clothing line for men and women, although as a preacher he continued sermonising against women's driving and their equal rights. Would it then be correct to say that the pop-singer-turned-preacher was the perfect embodiment of Pakistan's multiple contradictions:

- its movement between a moderate and a religious extremist country,

- its generosity and hypocrisy, and

- its love for music and equal contempt for culture and diversity.

At the other polar end of the spectrum was Rohail Hyatt, the founder of Vital Signs and the creator of Coke Studio – a brilliant innovation launched in 2008 that served as a spectacular renaissance in the Pakistani music scene. He redid traditional qawwalis, folk songs and ghazals through state-of-the-art equipment, modern aesthetics and fused them with cross-border influences. In multiple senses, he represents the emergence of a more liberal elite: younger Pakistanis aligned with their indigenous culture but brimming with multiple creative inspirations.

And he did this, from behind the scenes. This inconspicuousness has, somehow, been a constant in his life: from the heydays of Vital Signs: when all eyes would inevitably veer towards the eye candy that Junaid Jamshed was; to the Coke Studio (CS) era: where Rohail’s brilliance was known – but the toast of the season would, of course, be the singer; to the present day: where he is now quietly puppeteering the Velo Sound Station (VSS) platform while ensconced away in his home. It would then be fair enough to assume Rohail Hyatt ardently advocates multiculturalism.

Their disparate paths signify the deep split in our Pakistani society: a conflict between Pakistan’s dated forces of nature versus those striving for a more inclusive and aspirational future. And this is where the irony lies, because only time will tell whether Pakistani civic society chooses Junaid's conservatism or Rohail’s multiculturalism.