Yet again Urdu is being linked to one community. This flawed perception needs to be addressed for Urdu has no religion and it belongs to all those who understand and love it. “These thousands of excited men and women, mostly youth, tell you the reality that Urdu belongs to all and not Muslims only,” is how charming Bollywood star Waheeda Rehman opened Jashn-e-Rekhta’s season four in Delhi from December 8 to 10, 2017.

Celebrating Urdu as the organisers call it, the Jashn has in four years turned into a Junoon. The participation of Urdu lovers from across India belies the perception that the language is dying, but the perceived conformity continued to be discussed at the 4th edition as it was at the earlier ones. But the combinations and permutations that were the hallmark of the festival heralded a hope and that was the real take-away for thousands of people at the end of the three-day-long festival.

Besides Rehman another graceful addition at a panel discussion “Depiction of Urdu Culture in Muslim Social Films” was that of Shabana Azmi who again dispelled the notion that Urdu belonged to a particular religion. She cited Firaq Gorakhpuri and many others who made Urdu their love and wrote in the language all their lives. She was at pains to explain that Urdu represented a civilization that embodies everybody irrespective of religion, caste and creed. “Don’t link it to Muslims only; that is injustice. Do you think these thousands who are here to cherish its sweetness are all Muslims,” she pointed out to the crowd who responded with thunderous applause. Another filmmaker Muzaffar Ali too spoke on Urdu and the Muslim construct in the movies.

What is interesting is that Rekhta is growing, and its expansion and acceptability is something that even makes Sanjay Saraf nervous, the businessman-turned-Urdu evangelist who founded Rekhta in 2013. His objective was to make the riches of Urdu available to people online and he had 30,000 ghazals and nazams of around 2,500 writers uploaded with the meanings of complex words. Soon Rekhta replenished the language by reaching out to people with something that is in tune with demands of the new world. To many people’s delight, this Urdu “feast” included some surprising elements such as Tanya Wells who juggles a music career from Brazil to UK, the band Sukhan of Marathi-speaking youngsters and Parvaaz from Bengaluru. Wells mesmerized the audience with near-perfect diction and pronunciation. These talents attract youngsters who love Urdu poetry but may be handicapped as far as learning it goes. It was sad that no Pakistani artist or poet could come due to acrimony between the two countries but a befitting tribute to the legendary Jaun Elia directed by actor Fareed Kokab Fareed was something to relish. “Jannat se Jaun Elia ka Khat” depicts lives from Ghalib to Mir and Faraz in heaven and is written by Pakistani writer Anwar Maqsood. Fareed has reshaped it into a play.

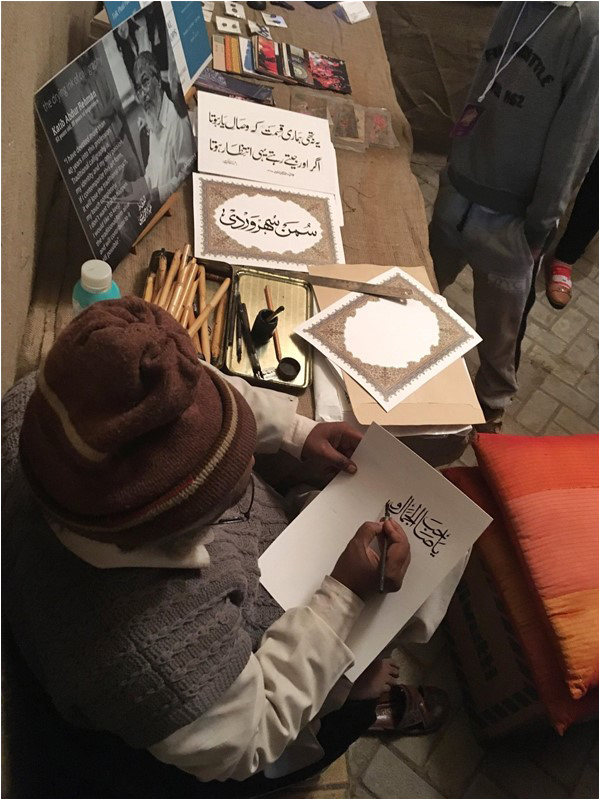

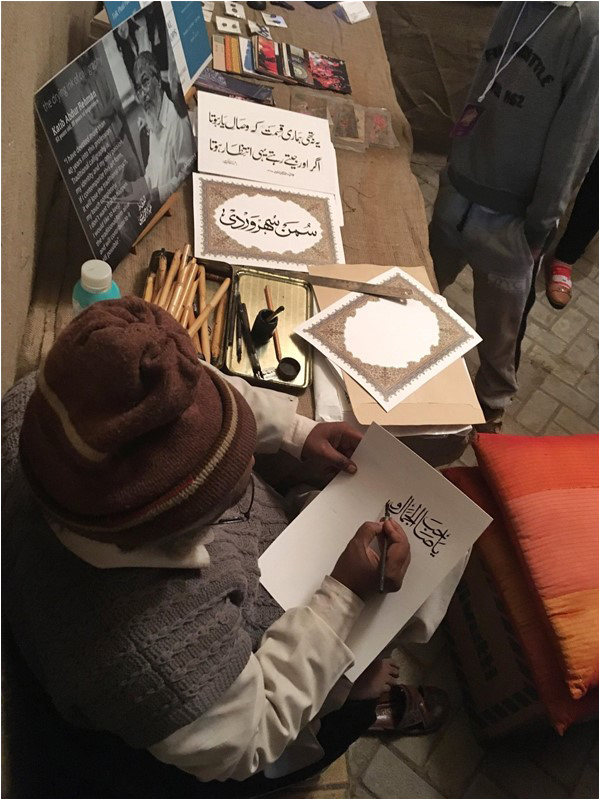

Not only is Rekhta a soothing treat for the eyes and ears with notable figures in Urdu but it is also an event that puts them in touch with the market for art. For example, the food court added to the flavours of Rekhta with creatives names such as Shaam-e-Awad, Litti, Kashmiri Wazwan and Ilham. In the crafts market, one could find Zarood, Ishq-e Urdu, Sufi Bazar and a perfect Urdu village where one can get closer to calligraphy. And of course, the books were a major attraction for those who mark the festival on their calendars.

Mantooyat

The highlight of this season’s Rekhta, however, was “Manto ke Rubaru”. Two popular stars of Bollywood known for their inimitable style were featured on the second day to rediscover legendary Saadat Hassan Manto. Nandita Das and Nawazuddin Siddiqui whose feature film “Manto” is soon hitting the screens spoke about the movie. Das was at her best as she deliberated on how she was convinced to have a movie on Manto.

“We need to know Manto if we are to serve and save our society, for one single fact that he was an embodiment of truth,” she said. She regretted that due to hostility between India and Pakistan she had to create “Lahore” in India rather than shoot the film in Lahore itself. The way she described Manto it was clear that she had absorbed him as a writer and was not wrong in coining an expression “Mantooyat” which she had imbibed. Nawaz admitted it was difficult to be Manto in the film as “he would always write truth in his stories”. “For me I had to be truthful and it is very difficult to be so in this world.” Both actors were acknowledged with resounding applause, proving what they said was well-received.

Conspiracy or trend

A common refrain about the decline of a language like Urdu is that it is facing a conspiracy to undermine it. But the fact is that Urdu is fighting for survival both in India and in Pakistan, although a majority of people in Pakistan speak, write and learn the language. In the absence of economic dividends even in Pakistan, where it is a national language, the younger generation is running away from it and adopting English. That is why the Pakistani government is contemplating replacing English with Urdu as an official language. However, there is resistance to that move from the Pakistani elite, who dominate the bureaucracy and policy-making. The real challenge to the language today is that it does not offer too many economic benefits, and those who relish and cherish it as a language to soothe their spirits are not to be found in large numbers.

In India too, where the language had been linked to Muslim identity, it does not have bright economic prospects. The number of people adopting it as a means to gain employment is dwindling. The policymakers ignore Urdu because it does not offer much in terms of economic progress, and all of this does not augur well for the future of the language.

Successive governments in India, though, have provided significant funds for the promotion of the language. While the total grant for promotion of Urdu language, provided by P.V. Narasimha Rao’s government was just Rs6 million, it saw a large increase during the NDA government led by A.B. Vajpayee. Under Murli Manohar Joshi as human resource development minister, the grant was increased to Rs50 million. In 2012-13 it was Rs400 million, and in the last budget it was increased further (although grants for the promotion of all Indian languages have been clubbed together). While the number of Urdu-medium schools has increased recently, and so has the financial support to them, the language is still facing challenges. Nevertheless, the trend among Muslims of India to identify with both Urdu and Hindustani is fast increasing. “The perception of Urdu as belonging to a larger community rather than just being identified with one particular religion is widespread and shared among Muslims and non-Muslims alike,” reveals a study ‘Whose Language is Urdu?’ conducted by Anvita Abbi, Imtiaz Hasnain and Ayesha Kidwai of the South Asia Institute at the Department of Political Science, University of Heidelberg. The trio conducted the study in Bihar, Lucknow, Mysore, Delhi and Simla.

No doubt, state patronage is necessary for a language as has been seen in past centuries when it came to Sanskrit and Persian. Although Urdu is the second official language in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi, challenges to its survival come from its original speakers, who feel that it is devoid of any benefit. A distinguished writer and poet Gopi Chand Narang may surely say that “Urdu is my identity,” but that does little to reassure the people of the viability of the language. Jammu and Kashmir is perhaps the only place where it does not face a threat despite being an alien language. But at the official level, it is true that the neglect is deep.

Notwithstanding these realities Rekhta has given rise to new hope. With more education young boys and girls are attracted to literature and Urdu provides a window to give vent to their feelings. That is perhaps what Rekhta is exploiting. While Saraf’s initiative should take a bow, it needs to be taken to different cities to make it pan-Indian and if political expediency is bulldozed, then to Pakistan as well.

The writer is a senior journalist based in Srinagar (Kashmir) and can be reached at shujaat7867@gmail.com

Celebrating Urdu as the organisers call it, the Jashn has in four years turned into a Junoon. The participation of Urdu lovers from across India belies the perception that the language is dying, but the perceived conformity continued to be discussed at the 4th edition as it was at the earlier ones. But the combinations and permutations that were the hallmark of the festival heralded a hope and that was the real take-away for thousands of people at the end of the three-day-long festival.

Besides Rehman another graceful addition at a panel discussion “Depiction of Urdu Culture in Muslim Social Films” was that of Shabana Azmi who again dispelled the notion that Urdu belonged to a particular religion. She cited Firaq Gorakhpuri and many others who made Urdu their love and wrote in the language all their lives. She was at pains to explain that Urdu represented a civilization that embodies everybody irrespective of religion, caste and creed. “Don’t link it to Muslims only; that is injustice. Do you think these thousands who are here to cherish its sweetness are all Muslims,” she pointed out to the crowd who responded with thunderous applause. Another filmmaker Muzaffar Ali too spoke on Urdu and the Muslim construct in the movies.

The highlight Rekhta was "Manto ke Rubaru". Two stars of Bollywood rediscovered legendary Saadat Hassan Manto. Nandita Das and Nawazuddin Siddiqui whose feature film "Manto" is soon hitting the screens spoke about the movie

What is interesting is that Rekhta is growing, and its expansion and acceptability is something that even makes Sanjay Saraf nervous, the businessman-turned-Urdu evangelist who founded Rekhta in 2013. His objective was to make the riches of Urdu available to people online and he had 30,000 ghazals and nazams of around 2,500 writers uploaded with the meanings of complex words. Soon Rekhta replenished the language by reaching out to people with something that is in tune with demands of the new world. To many people’s delight, this Urdu “feast” included some surprising elements such as Tanya Wells who juggles a music career from Brazil to UK, the band Sukhan of Marathi-speaking youngsters and Parvaaz from Bengaluru. Wells mesmerized the audience with near-perfect diction and pronunciation. These talents attract youngsters who love Urdu poetry but may be handicapped as far as learning it goes. It was sad that no Pakistani artist or poet could come due to acrimony between the two countries but a befitting tribute to the legendary Jaun Elia directed by actor Fareed Kokab Fareed was something to relish. “Jannat se Jaun Elia ka Khat” depicts lives from Ghalib to Mir and Faraz in heaven and is written by Pakistani writer Anwar Maqsood. Fareed has reshaped it into a play.

Not only is Rekhta a soothing treat for the eyes and ears with notable figures in Urdu but it is also an event that puts them in touch with the market for art. For example, the food court added to the flavours of Rekhta with creatives names such as Shaam-e-Awad, Litti, Kashmiri Wazwan and Ilham. In the crafts market, one could find Zarood, Ishq-e Urdu, Sufi Bazar and a perfect Urdu village where one can get closer to calligraphy. And of course, the books were a major attraction for those who mark the festival on their calendars.

Mantooyat

The highlight of this season’s Rekhta, however, was “Manto ke Rubaru”. Two popular stars of Bollywood known for their inimitable style were featured on the second day to rediscover legendary Saadat Hassan Manto. Nandita Das and Nawazuddin Siddiqui whose feature film “Manto” is soon hitting the screens spoke about the movie. Das was at her best as she deliberated on how she was convinced to have a movie on Manto.

“We need to know Manto if we are to serve and save our society, for one single fact that he was an embodiment of truth,” she said. She regretted that due to hostility between India and Pakistan she had to create “Lahore” in India rather than shoot the film in Lahore itself. The way she described Manto it was clear that she had absorbed him as a writer and was not wrong in coining an expression “Mantooyat” which she had imbibed. Nawaz admitted it was difficult to be Manto in the film as “he would always write truth in his stories”. “For me I had to be truthful and it is very difficult to be so in this world.” Both actors were acknowledged with resounding applause, proving what they said was well-received.

Conspiracy or trend

A common refrain about the decline of a language like Urdu is that it is facing a conspiracy to undermine it. But the fact is that Urdu is fighting for survival both in India and in Pakistan, although a majority of people in Pakistan speak, write and learn the language. In the absence of economic dividends even in Pakistan, where it is a national language, the younger generation is running away from it and adopting English. That is why the Pakistani government is contemplating replacing English with Urdu as an official language. However, there is resistance to that move from the Pakistani elite, who dominate the bureaucracy and policy-making. The real challenge to the language today is that it does not offer too many economic benefits, and those who relish and cherish it as a language to soothe their spirits are not to be found in large numbers.

In India too, where the language had been linked to Muslim identity, it does not have bright economic prospects. The number of people adopting it as a means to gain employment is dwindling. The policymakers ignore Urdu because it does not offer much in terms of economic progress, and all of this does not augur well for the future of the language.

Successive governments in India, though, have provided significant funds for the promotion of the language. While the total grant for promotion of Urdu language, provided by P.V. Narasimha Rao’s government was just Rs6 million, it saw a large increase during the NDA government led by A.B. Vajpayee. Under Murli Manohar Joshi as human resource development minister, the grant was increased to Rs50 million. In 2012-13 it was Rs400 million, and in the last budget it was increased further (although grants for the promotion of all Indian languages have been clubbed together). While the number of Urdu-medium schools has increased recently, and so has the financial support to them, the language is still facing challenges. Nevertheless, the trend among Muslims of India to identify with both Urdu and Hindustani is fast increasing. “The perception of Urdu as belonging to a larger community rather than just being identified with one particular religion is widespread and shared among Muslims and non-Muslims alike,” reveals a study ‘Whose Language is Urdu?’ conducted by Anvita Abbi, Imtiaz Hasnain and Ayesha Kidwai of the South Asia Institute at the Department of Political Science, University of Heidelberg. The trio conducted the study in Bihar, Lucknow, Mysore, Delhi and Simla.

No doubt, state patronage is necessary for a language as has been seen in past centuries when it came to Sanskrit and Persian. Although Urdu is the second official language in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi, challenges to its survival come from its original speakers, who feel that it is devoid of any benefit. A distinguished writer and poet Gopi Chand Narang may surely say that “Urdu is my identity,” but that does little to reassure the people of the viability of the language. Jammu and Kashmir is perhaps the only place where it does not face a threat despite being an alien language. But at the official level, it is true that the neglect is deep.

Notwithstanding these realities Rekhta has given rise to new hope. With more education young boys and girls are attracted to literature and Urdu provides a window to give vent to their feelings. That is perhaps what Rekhta is exploiting. While Saraf’s initiative should take a bow, it needs to be taken to different cities to make it pan-Indian and if political expediency is bulldozed, then to Pakistan as well.

The writer is a senior journalist based in Srinagar (Kashmir) and can be reached at shujaat7867@gmail.com