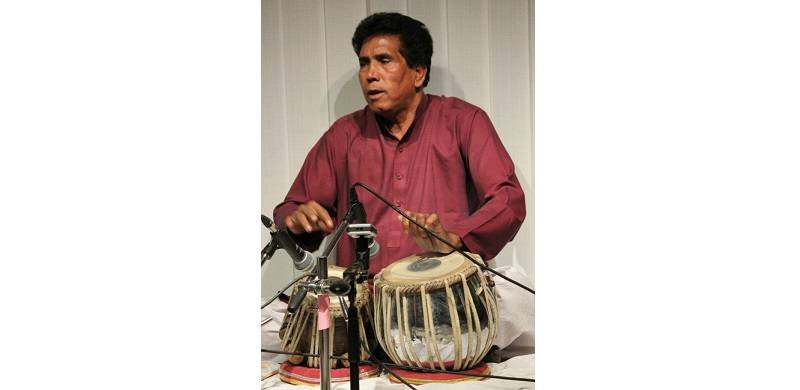

It seem that now and in the coming days, we will have nothing else to do except mourning the death of friends – not ordinary but rare in their renown, modesty and humanity besides art and skills. So today, the new year has condemned us to mourn the death of classical tabla in the Potohar region, for Ejaz Hussain Jajji is among us no more.

Ejaz – the sole exponent of classical tabla in Rawalpindi – was seriously ill for the past few months. I met him last summer at his small half-room music academy in Banni, Rawalpindi. He was very sad. He wanted to have a plot of five marla that was sanctioned by General Musharraf when he was in power. He struggled to get it for more than two decades. He begged every bigwig for it. He failed to get it, but he was successful in securing an important piece of land: two yards, in the form of a grave that a rich and powerful man like General Zia could never find.

Ejaz was around 72. He passed away on 13 January 2023 due to multiple organ failure. Diabetes had turned a huge and muscular Ejaz to a scrawny Jajji. In the same meeting, he wanted me to spend a full day with him so that he could teach me some rare compositions. I could never spare a day. And now I feel I committed a sin that is beyond repentance.

His friends won’t call him Ejaz but Jajji. He was teasing the late Shaukat Mirza in 1992 at Sur Sajjan (a weekly music soiree that the Pakistan National Council of Arts – PNCA – would hold). Mirza was singing a ghazal. Ejaz was disturbing him by playing too loud. I could have seen the annoyance on Mirza’s face. I was 23 then. I stood up and gave Jajji a piece of my mind, saying: “Play straight beat-cycle (theka) and don’t spoil the pathos of music.” I was quite rude, but Jujii was great. He kept the theka straight. Mirza sent a gesture of thanks from the stage. And we three became good friends. Mirza passed away after a few years, and Jajji has just joined him in the Hereafter.

Jajji had unique background. According to my friend Agha Khalid Zubair (a fine kathak dancer as well as a former PNCA director), Jajji was trained not only in tabla-playing but also in tabla-manufacturing. Sharif Saheb (Jajji’s father) was Rawalpindi’s best tabla-maker. And he was also the best in supardaari. If a musician teams up with tawaifs (dancing girls) and accompanies them on his instrument (tabla, sarangi, harmonium, etc), this trade in music parlance is called supardaari. Khan Sahebs (famed practitioners of classical music like Ustad Amir Khan, Ustad Vilayat Khan, etc) would look down on those in the field of supardaari.

Jajji made his name in supardaari. He was tall and robust like a wrestler. He could play tabla vigorously for hours non-stop, without any sound system. The tabla in dance is always loud and played with open hands. Thus, his tonal quality became very powerful – which was not good if he had to accompany a classical vocalist or an instrumentalist. A time came soon when kotha (dancing girls’ music hall where listeners would come, watch them dancing and throw money generously) culture was replaced by General Zia’s Islam. Jajji had no difficulty in accompanying vocalists, instrumentalists or ghazal/qawwali/geet singers. According to Agha saheb, dance-tabla is the most difficult to master. Once it has been learnt, any other form of sangat can be learnt easily. Jajji was mentored in vocal sangat by Ustad Salamat Ali Khan and in light music sangat by the violinist Rais Khan. Jajji was the most favourite tabla accompanist of Pakistan’s sole sarod player Asad Qazilbash. The latter taught him how to accompany a sarod player. Jajji’s tabla would sound extremely soft and yet sonorous when he would accompany Asad.

Jajji was an exponent of the famous Punjab gharana. He learned tabla from Ustad Akthar Hussain Shera, who was a disciple of Ustad Alla Ditta Biharipur. The latter was the student of Ustad Nabi Baksh Kalray Wale – a unique world in the realm of tabla. Like any renowned artist, Jajji made a lot of money and spent it all the same day. With the demise of classical vocalists and ghazal singers, he was left with no work. For years, he would not play in concerts but small wedding functions that barely ensured him bread and butter.

After the death of ustads, Pindi was left with just two artists who could have played classical-style tabla. One was Mohammad Ajmal who passed away on 18 December 2019. Jajji’s death is the death and burial of classical tabla in Rawalpindi. If you have to base your compositions on intricate rhythmic cycles like talwara, jhoomra, aada chautala or odd beats like 9, 11, 13, 15 or their halves or quarters or three-fourths, you will have to import a tabla player from Lahore or Karachi. One option will be the Peshawar-based brilliant tabla player Sabz Ali. And if these tabla players are unable to come to Islamabad due to any reason, then you will have to invite someone from India!

Jajji’s ustad was able to produce one Jajji but he could not produce another Jajji. Ironic! Not because he was not sincere in teaching tabla. For, nobody would like to work so hard. Look at me. He wanted to gift me some rare compositions if I gave him a day. I could never visit him. So, the culprit is not the ustad but the lazy shagird like myself.

Ejaz – the sole exponent of classical tabla in Rawalpindi – was seriously ill for the past few months. I met him last summer at his small half-room music academy in Banni, Rawalpindi. He was very sad. He wanted to have a plot of five marla that was sanctioned by General Musharraf when he was in power. He struggled to get it for more than two decades. He begged every bigwig for it. He failed to get it, but he was successful in securing an important piece of land: two yards, in the form of a grave that a rich and powerful man like General Zia could never find.

Ejaz was around 72. He passed away on 13 January 2023 due to multiple organ failure. Diabetes had turned a huge and muscular Ejaz to a scrawny Jajji. In the same meeting, he wanted me to spend a full day with him so that he could teach me some rare compositions. I could never spare a day. And now I feel I committed a sin that is beyond repentance.

His friends won’t call him Ejaz but Jajji. He was teasing the late Shaukat Mirza in 1992 at Sur Sajjan (a weekly music soiree that the Pakistan National Council of Arts – PNCA – would hold). Mirza was singing a ghazal. Ejaz was disturbing him by playing too loud. I could have seen the annoyance on Mirza’s face. I was 23 then. I stood up and gave Jajji a piece of my mind, saying: “Play straight beat-cycle (theka) and don’t spoil the pathos of music.” I was quite rude, but Jujii was great. He kept the theka straight. Mirza sent a gesture of thanks from the stage. And we three became good friends. Mirza passed away after a few years, and Jajji has just joined him in the Hereafter.

Jajji was an exponent of the famous Punjab gharana. He learned tabla from Ustad Akthar Hussain Shera, who was a disciple of Ustad Alla Ditta Biharipur. The latter was the student of Ustad Nabi Baksh Kalray Wale – unique in the realm of tabla

Jajji had unique background. According to my friend Agha Khalid Zubair (a fine kathak dancer as well as a former PNCA director), Jajji was trained not only in tabla-playing but also in tabla-manufacturing. Sharif Saheb (Jajji’s father) was Rawalpindi’s best tabla-maker. And he was also the best in supardaari. If a musician teams up with tawaifs (dancing girls) and accompanies them on his instrument (tabla, sarangi, harmonium, etc), this trade in music parlance is called supardaari. Khan Sahebs (famed practitioners of classical music like Ustad Amir Khan, Ustad Vilayat Khan, etc) would look down on those in the field of supardaari.

Jajji made his name in supardaari. He was tall and robust like a wrestler. He could play tabla vigorously for hours non-stop, without any sound system. The tabla in dance is always loud and played with open hands. Thus, his tonal quality became very powerful – which was not good if he had to accompany a classical vocalist or an instrumentalist. A time came soon when kotha (dancing girls’ music hall where listeners would come, watch them dancing and throw money generously) culture was replaced by General Zia’s Islam. Jajji had no difficulty in accompanying vocalists, instrumentalists or ghazal/qawwali/geet singers. According to Agha saheb, dance-tabla is the most difficult to master. Once it has been learnt, any other form of sangat can be learnt easily. Jajji was mentored in vocal sangat by Ustad Salamat Ali Khan and in light music sangat by the violinist Rais Khan. Jajji was the most favourite tabla accompanist of Pakistan’s sole sarod player Asad Qazilbash. The latter taught him how to accompany a sarod player. Jajji’s tabla would sound extremely soft and yet sonorous when he would accompany Asad.

Jajji was an exponent of the famous Punjab gharana. He learned tabla from Ustad Akthar Hussain Shera, who was a disciple of Ustad Alla Ditta Biharipur. The latter was the student of Ustad Nabi Baksh Kalray Wale – a unique world in the realm of tabla. Like any renowned artist, Jajji made a lot of money and spent it all the same day. With the demise of classical vocalists and ghazal singers, he was left with no work. For years, he would not play in concerts but small wedding functions that barely ensured him bread and butter.

After the death of ustads, Pindi was left with just two artists who could have played classical-style tabla. One was Mohammad Ajmal who passed away on 18 December 2019. Jajji’s death is the death and burial of classical tabla in Rawalpindi. If you have to base your compositions on intricate rhythmic cycles like talwara, jhoomra, aada chautala or odd beats like 9, 11, 13, 15 or their halves or quarters or three-fourths, you will have to import a tabla player from Lahore or Karachi. One option will be the Peshawar-based brilliant tabla player Sabz Ali. And if these tabla players are unable to come to Islamabad due to any reason, then you will have to invite someone from India!

Jajji’s ustad was able to produce one Jajji but he could not produce another Jajji. Ironic! Not because he was not sincere in teaching tabla. For, nobody would like to work so hard. Look at me. He wanted to gift me some rare compositions if I gave him a day. I could never visit him. So, the culprit is not the ustad but the lazy shagird like myself.