The experts say the water supply in Lahore is dying. A half-full canteen, cap open, dissolving in the desert heat. A glacial stream, bogged down by biscuit wrappers and bottled water six-packs, giving itself over to the scorching sun. I think of the Indus.

When I was trapped an ocean away in Texas, I thought of it often. The Indus used to beat a lovesick refrain in the back of my head. I dreamt of returning, one day, to a homeland, Roots-style, reverse-exodus. In elementary school, I would come excited to “show and tell” and I would tell about the pink dolphins in the Indus, the ones I’d seen in patriotic picture books, swishing and splashing through our land of beauty. How exciting for a young girl - dolphins! And pink! Pakistan seemed like a land of endless adventure then. But the pink dolphins, now endangered by decades of water mismanagement and pollution, don’t come up for air any more, and the river is losing its grasp. Those things I dreamt of returning to are half gone already, and the other half are disappearing fast.

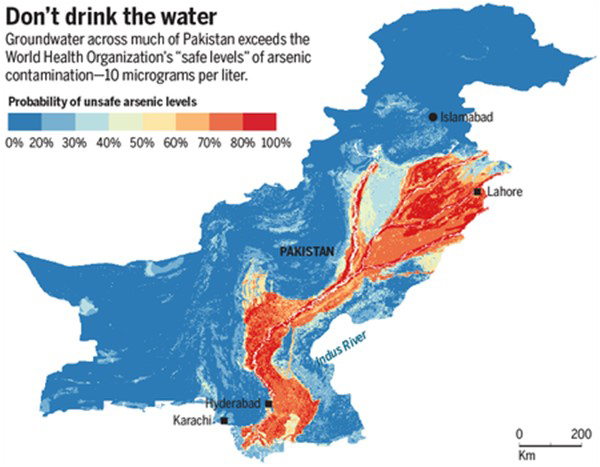

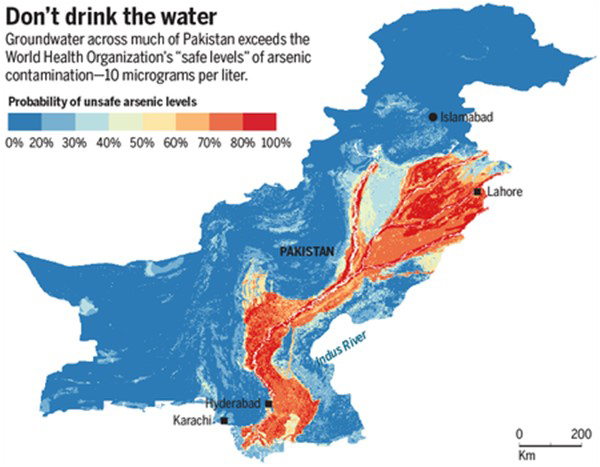

What ails the water? First there is the utter failure of governance when it comes to proper management and distribution of our water supply, manifested in various ways: widespread illegal ground water boring/pumping, near total dependency on groundwater for domestic/industrial uses and depleting aquifers. Due to lax and unenforced environmental regulation as well as cultural mores, direct dumping of toxic products into the water supply is common. Stats say that polluted water may cause up to 40% of all the deaths in Pakistan – as bacteria, nitrates, fluoride and even arsenic find their way into the country’s drinking water supply. Then looms the spectre of global warming, affecting us more acutely than most. The Himalayan glaciers supply our rivers and cause intermittent floods as they melt. But as the glacier ice sheet recedes more and more, so will our rivers.

That is what the experts say.

And then there is what my friends say: Pani ka masla? Kya masla? Nestle ke bottle peete rehna! (Water problem? What problem? Just keep drinking Nestle bottled water)

So what if the canals are dirty, reeking of typhoid, the poor man’s lungs shirking back and leaping out of his body? We don’t have a problem. Tumhe kya? And it is a sentiment certain parts of Lahore – the parts which are cloistered, arrogant, reeking of wealth – echo in droves. They haven’t realised yet that wealth, while an incredible insulator from many social ills, cannot protect them from environmental destruction. Yes, we can live in our enclaves safe from terrorism and homeless people, but pollution doesn’t know to show its ID at Cantt. checkpoints. It simply floats on through. When the country rots, we all rot with it. When the shoe drops, we all fall with it. Even Nestle cannot save us.

Some say it’s easy: just use less water! These are the posts which have been circulating on social media lately. Suddenly, it appears, someone cares about water, or cares very much about Kalabagh Dam, a few weeks before the election. Take shorter showers, don’t water your grass, people have been echoing. You know, they say, if people in this country weren’t so jahil (ignorant) we wouldn’t have a water overuse problem. This is an interesting supposition – because we don’t actually have a water overuse problem. We have a water mismanagement problem, a water contamination problem, a water-screwed-by-government-institutions-and-big-business problem.

I ask one of the prominent water experts in Punjab: if I take shorter showers will it all be fixed? He says that if every single person in the country does their individual parts, it will fix 1% of the problem. Which, as you can surmise, will do jacks**t!

The odd transplantation of responsibility for environmental damage caused by institutions onto the average person is a worldwide phenomenon. Take the American ‘Go Green’ movement: we presuppose if each one of us composts and lives trash-free, everything will be solved. But the average citizen’s habits didn’t cause environmental devastation, and they cannot reverse it. It is industry – the great big smoking shadow of it – which has ruined our crops and fields, dumped arsenic in our freshwater streams, and cut our country off at the knees. It is government, bloated, content, and too willing to close its eyes and ears, which has twiddled its thumbs and let it happen. We can take short showers all we want; it still won’t make a difference. The change we need is too massive for our individual contributions to make a difference. Our individual contributions need to be directed, instead, towards forcing the large-scale polluters in our country and government regulators to change.

Still, there are those who find this entire conversation hogwash. Environmental concerns? Those are for trust-fund babies in Portland and American hippies: we simply do not have the time. When a land’s systems are crumbling, indeed, who has time for the land? In 10 or 20 years the system, a new one, will still be crumbling, and we will be facing a reckoning with the land which cares not for our political intrigues. Soon we might be faced with a Lahore that is scorched earth, where the very soil repels us and our countrymen fall like flies to the plagues of heatstroke and waterborne illnesses.

What can be more of a pressing concern?

When I was trapped an ocean away in Texas, I thought of it often. The Indus used to beat a lovesick refrain in the back of my head. I dreamt of returning, one day, to a homeland, Roots-style, reverse-exodus. In elementary school, I would come excited to “show and tell” and I would tell about the pink dolphins in the Indus, the ones I’d seen in patriotic picture books, swishing and splashing through our land of beauty. How exciting for a young girl - dolphins! And pink! Pakistan seemed like a land of endless adventure then. But the pink dolphins, now endangered by decades of water mismanagement and pollution, don’t come up for air any more, and the river is losing its grasp. Those things I dreamt of returning to are half gone already, and the other half are disappearing fast.

What ails the water? First there is the utter failure of governance when it comes to proper management and distribution of our water supply, manifested in various ways: widespread illegal ground water boring/pumping, near total dependency on groundwater for domestic/industrial uses and depleting aquifers. Due to lax and unenforced environmental regulation as well as cultural mores, direct dumping of toxic products into the water supply is common. Stats say that polluted water may cause up to 40% of all the deaths in Pakistan – as bacteria, nitrates, fluoride and even arsenic find their way into the country’s drinking water supply. Then looms the spectre of global warming, affecting us more acutely than most. The Himalayan glaciers supply our rivers and cause intermittent floods as they melt. But as the glacier ice sheet recedes more and more, so will our rivers.

That is what the experts say.

And then there is what my friends say: Pani ka masla? Kya masla? Nestle ke bottle peete rehna! (Water problem? What problem? Just keep drinking Nestle bottled water)

So what if the canals are dirty, reeking of typhoid, the poor man’s lungs shirking back and leaping out of his body? We don’t have a problem. Tumhe kya? And it is a sentiment certain parts of Lahore – the parts which are cloistered, arrogant, reeking of wealth – echo in droves. They haven’t realised yet that wealth, while an incredible insulator from many social ills, cannot protect them from environmental destruction. Yes, we can live in our enclaves safe from terrorism and homeless people, but pollution doesn’t know to show its ID at Cantt. checkpoints. It simply floats on through. When the country rots, we all rot with it. When the shoe drops, we all fall with it. Even Nestle cannot save us.

I ask one of the prominent water experts in Punjab: if I take shorter showers will it all be fixed? He says that if every single person in the country does their individual parts, it will fix 1% of the problem

Some say it’s easy: just use less water! These are the posts which have been circulating on social media lately. Suddenly, it appears, someone cares about water, or cares very much about Kalabagh Dam, a few weeks before the election. Take shorter showers, don’t water your grass, people have been echoing. You know, they say, if people in this country weren’t so jahil (ignorant) we wouldn’t have a water overuse problem. This is an interesting supposition – because we don’t actually have a water overuse problem. We have a water mismanagement problem, a water contamination problem, a water-screwed-by-government-institutions-and-big-business problem.

I ask one of the prominent water experts in Punjab: if I take shorter showers will it all be fixed? He says that if every single person in the country does their individual parts, it will fix 1% of the problem. Which, as you can surmise, will do jacks**t!

The odd transplantation of responsibility for environmental damage caused by institutions onto the average person is a worldwide phenomenon. Take the American ‘Go Green’ movement: we presuppose if each one of us composts and lives trash-free, everything will be solved. But the average citizen’s habits didn’t cause environmental devastation, and they cannot reverse it. It is industry – the great big smoking shadow of it – which has ruined our crops and fields, dumped arsenic in our freshwater streams, and cut our country off at the knees. It is government, bloated, content, and too willing to close its eyes and ears, which has twiddled its thumbs and let it happen. We can take short showers all we want; it still won’t make a difference. The change we need is too massive for our individual contributions to make a difference. Our individual contributions need to be directed, instead, towards forcing the large-scale polluters in our country and government regulators to change.

Still, there are those who find this entire conversation hogwash. Environmental concerns? Those are for trust-fund babies in Portland and American hippies: we simply do not have the time. When a land’s systems are crumbling, indeed, who has time for the land? In 10 or 20 years the system, a new one, will still be crumbling, and we will be facing a reckoning with the land which cares not for our political intrigues. Soon we might be faced with a Lahore that is scorched earth, where the very soil repels us and our countrymen fall like flies to the plagues of heatstroke and waterborne illnesses.

What can be more of a pressing concern?