Pakistan is facing difficult times. Our economic performance has been dismal, with GDP growth rates slower than almost all Asian countries. In recent months high food price inflation has hammered the poor. And now the COVID-19 pandemic is playing its own peculiar havoc causing immense problems for everyone, but particularly for small businesses and daily wage workers. Across the border, a Hindu-first narrative is being pushed which portrays Muslims, and by implication Pakistanis, as uncultured and aggressive invaders of an ancient and peaceful Hindu motherland. At the same time, the USA and China are jostling each other for our loyalty.

We must make some tough decisions on the economic front to catch up with other countries, and on the political and foreign policy front to find a stronger and better role in the region and the world. This means some hard decisions need to be made on policy and programmatic fronts. But implementing policies and programs means that we must come together as a nation, putting aside our differences. For this to happen, it is imperative that we build a strong inclusive narrative about what it means to be Pakistani; who we are and where do we come from; and what are our rights and obligations towards each other. Only then will we be able to move ahead turning our backs on the tendency to blame other for our problems; and from the divisive ethnic, linguistic and religious politics that has been so characteristic of the past decades.

This is going to be hard as recent history had not been kind to us. Over the last 70 years Pakistan has lived through highly traumatic events that have shaken out our ability to think positively about ourselves and our future. Amongst these events, maybe the most difficult was in 1971 when East Pakistan seceded. At that time, the area that became Bangladesh was poorer and considered to have little growth potential. Many Pakistanis were even of the view that West Pakistan, being richer and better endowed with natural resources, would be better off without East Pakistan. However, Bangladesh’s better performance with regard to economic growth, education and health has highlighted Pakistan’s poor management on these crucial fronts. This has certainly eroded national confidence in our leadership and intellectuals who are responsible for policies and programs. Other difficult events we have lived through are related to the war in Afghanistan which brought us 4 million refugees, gun culture and drugs; and terrorism which caused 65,000 deaths and economic losses worth US$70 billion.

But we need to recall that many other countries have lived through traumatic times. At the end of the Second World War in 1945, much of Europe, as well as Russia and Japan, had suffered huge destruction with cities razed to the ground and their economies shattered. Similarly, China at the time of its independence in 1949 was in economic and social ruins. However, a strong national spirit and a shared commitment helped these countries rebuild their economies, as well as their social and institutional structures.

So how does one build a renewed “national spirit,” where the common good is seen as more important than self-interest? While exhorting speeches by charismatic leaders will do much to create such a national spirit, a better understanding of history is also critical. History gives us a sense of identity. It tells us where we came from and, most importantly, it helps us come together. A good knowledge of history is critical for any country and particularly so for countries like Pakistan, founded not on the basis of language, ethnicity or geography, but on the basis of ideologies and ideas.

Much of the history currently taught in schools starts from the Arab and Mongol invasions which brought Islam to the subcontinent. This is certainly an important part of our history and national identity. However, our history goes back much further. The land that is now Pakistan was the heartland of the Indus Valley Civilization and its precursor civilizations. Our history dates back to at several thousand years B.C. - and possibly predates even those that of Mesopotamia. We Pakistanis are also a product of this “deeper history” and we need to draw strength from this.

So what are some of the main milestones in our deeper history? Archaeological work performed at Mehrgarh in Balochistan shows settlements dating back to over 7,000 B.C. This was likely the earliest centre of agriculture in South Asia. There have been findings of sea shells and lapis lazuli that show trading links with far flung areas. Incredibly some skulls dating back to this period show evidence of primitive dentistry!

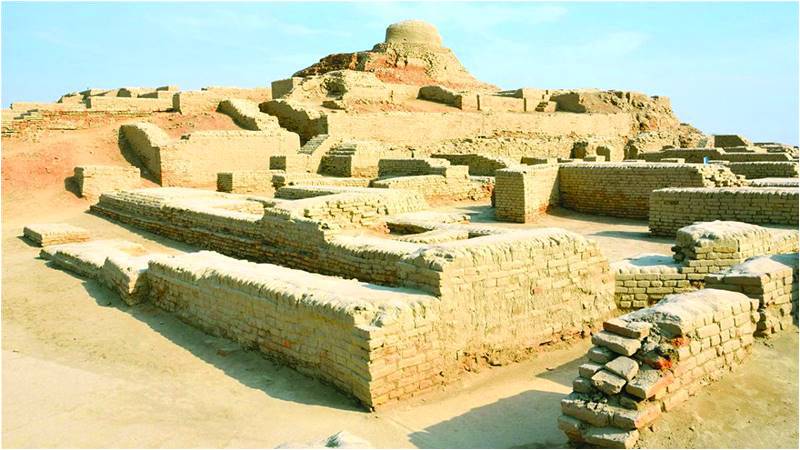

Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro, and other cities of the Indus Valley civilization were technologically, economically and socially advanced societies with much of the population living in large, well-planned cities with straight streets, well laid-out houses, public water supply, good sewage, and waste collection points at every street corner. There is evidence of trade links as far as Mesopotamia and Egypt. They also appear to be highly democratic and egalitarian societies as evidenced by the fact that archeologists have not found many magnificent palaces and temples where the social or political elites would have lived.

At Taxila we have a settlement whose history is as fascinating as those of Mehrgarh or Mohenjo-Daro. As a city it dates back to 1,000 B.C. and its location, on the on the great trade routes of the ancient world, gave it tremendous cultural, social and economic importance. The Mahabarata was apparently first recited at Taxila. One of the earliest, or possibly even the earliest, universities in the world was located there. Ancient Hindu and Buddhist texts attest to its wealth and its importance as a center of learning.

This deeper history certainly helps explains many of the characteristics which make us Pakistanis - characteristics such as tolerance and kindness; love of music, poetry and dance; and altruism and generosity. It also explains our tendency to build syncretic, as opposed to exclusive, belief systems ranging from Sufi traditions of Sindh and southern Punjab, to the gentle and peaceful Nurbakshis in Baltistan.

There are two concrete steps we need to take in order to create a more positive narrative about our cultural identity as Pakistanis.

Firstly, we need this “deeper history” to become mainstreamed into our national self-image. This can be done by intellectuals and media that could bring this topic into focus and introduce it within the national discourse. An essential aspect is greater attention being given in the education system. The school curricula are being currently revised and this is an excellent time to ensure that the study of our history, starting from the Neolithic, should be prioritized.

Secondly, we need to make much bigger investments of time and money to discover more about the above mentioned civilizations. The major excavations and discoveries have been done in British times using the techniques and technologies of the time; today we have more advanced tools and knowledge. We need to re-launch this work and historians, archaeologists and economists need to work much more closely with each other to help us understand who we are.

Daud Khan is an ex-UN staff member who lives between Rome and Pakistan.

Leila Yasmine Khan is an independent writer and editor based in the Netherlands.

We must make some tough decisions on the economic front to catch up with other countries, and on the political and foreign policy front to find a stronger and better role in the region and the world. This means some hard decisions need to be made on policy and programmatic fronts. But implementing policies and programs means that we must come together as a nation, putting aside our differences. For this to happen, it is imperative that we build a strong inclusive narrative about what it means to be Pakistani; who we are and where do we come from; and what are our rights and obligations towards each other. Only then will we be able to move ahead turning our backs on the tendency to blame other for our problems; and from the divisive ethnic, linguistic and religious politics that has been so characteristic of the past decades.

This is going to be hard as recent history had not been kind to us. Over the last 70 years Pakistan has lived through highly traumatic events that have shaken out our ability to think positively about ourselves and our future. Amongst these events, maybe the most difficult was in 1971 when East Pakistan seceded. At that time, the area that became Bangladesh was poorer and considered to have little growth potential. Many Pakistanis were even of the view that West Pakistan, being richer and better endowed with natural resources, would be better off without East Pakistan. However, Bangladesh’s better performance with regard to economic growth, education and health has highlighted Pakistan’s poor management on these crucial fronts. This has certainly eroded national confidence in our leadership and intellectuals who are responsible for policies and programs. Other difficult events we have lived through are related to the war in Afghanistan which brought us 4 million refugees, gun culture and drugs; and terrorism which caused 65,000 deaths and economic losses worth US$70 billion.

This deeper history certainly helps explains many of the characteristics which make us Pakistanis - characteristics such as tolerance and kindness; love of music, poetry and dance; and altruism and generosity

But we need to recall that many other countries have lived through traumatic times. At the end of the Second World War in 1945, much of Europe, as well as Russia and Japan, had suffered huge destruction with cities razed to the ground and their economies shattered. Similarly, China at the time of its independence in 1949 was in economic and social ruins. However, a strong national spirit and a shared commitment helped these countries rebuild their economies, as well as their social and institutional structures.

So how does one build a renewed “national spirit,” where the common good is seen as more important than self-interest? While exhorting speeches by charismatic leaders will do much to create such a national spirit, a better understanding of history is also critical. History gives us a sense of identity. It tells us where we came from and, most importantly, it helps us come together. A good knowledge of history is critical for any country and particularly so for countries like Pakistan, founded not on the basis of language, ethnicity or geography, but on the basis of ideologies and ideas.

Much of the history currently taught in schools starts from the Arab and Mongol invasions which brought Islam to the subcontinent. This is certainly an important part of our history and national identity. However, our history goes back much further. The land that is now Pakistan was the heartland of the Indus Valley Civilization and its precursor civilizations. Our history dates back to at several thousand years B.C. - and possibly predates even those that of Mesopotamia. We Pakistanis are also a product of this “deeper history” and we need to draw strength from this.

So what are some of the main milestones in our deeper history? Archaeological work performed at Mehrgarh in Balochistan shows settlements dating back to over 7,000 B.C. This was likely the earliest centre of agriculture in South Asia. There have been findings of sea shells and lapis lazuli that show trading links with far flung areas. Incredibly some skulls dating back to this period show evidence of primitive dentistry!

Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro, and other cities of the Indus Valley civilization were technologically, economically and socially advanced societies with much of the population living in large, well-planned cities with straight streets, well laid-out houses, public water supply, good sewage, and waste collection points at every street corner. There is evidence of trade links as far as Mesopotamia and Egypt. They also appear to be highly democratic and egalitarian societies as evidenced by the fact that archeologists have not found many magnificent palaces and temples where the social or political elites would have lived.

At Taxila we have a settlement whose history is as fascinating as those of Mehrgarh or Mohenjo-Daro. As a city it dates back to 1,000 B.C. and its location, on the on the great trade routes of the ancient world, gave it tremendous cultural, social and economic importance. The Mahabarata was apparently first recited at Taxila. One of the earliest, or possibly even the earliest, universities in the world was located there. Ancient Hindu and Buddhist texts attest to its wealth and its importance as a center of learning.

This deeper history certainly helps explains many of the characteristics which make us Pakistanis - characteristics such as tolerance and kindness; love of music, poetry and dance; and altruism and generosity. It also explains our tendency to build syncretic, as opposed to exclusive, belief systems ranging from Sufi traditions of Sindh and southern Punjab, to the gentle and peaceful Nurbakshis in Baltistan.

There are two concrete steps we need to take in order to create a more positive narrative about our cultural identity as Pakistanis.

Firstly, we need this “deeper history” to become mainstreamed into our national self-image. This can be done by intellectuals and media that could bring this topic into focus and introduce it within the national discourse. An essential aspect is greater attention being given in the education system. The school curricula are being currently revised and this is an excellent time to ensure that the study of our history, starting from the Neolithic, should be prioritized.

Secondly, we need to make much bigger investments of time and money to discover more about the above mentioned civilizations. The major excavations and discoveries have been done in British times using the techniques and technologies of the time; today we have more advanced tools and knowledge. We need to re-launch this work and historians, archaeologists and economists need to work much more closely with each other to help us understand who we are.

Daud Khan is an ex-UN staff member who lives between Rome and Pakistan.

Leila Yasmine Khan is an independent writer and editor based in the Netherlands.