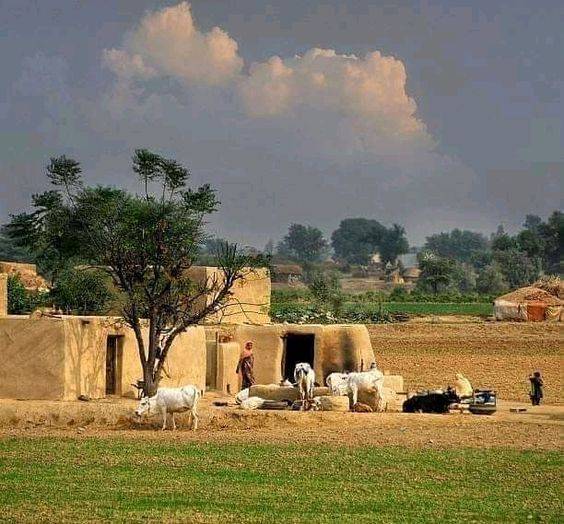

Nestled within the fertile agricultural landscape of Sindh, at the edge of a village or alongside a minor canal, tiny hamlets are commonly referred to in the Sindhi language as Pahenja Ghar (Our Own Houses). The establishment of these tiny villages presents a fascinating opportunity to learn about community dynamics and family structures. The formation of these hamlets often reflects deeper sociocultural processes, particularly among families that choose to separate from their extended kin to create distinct living spaces. The phenomenon of these spin-off villages highlights the interplay between tradition, family relationships, and the quest for autonomy.

When I spoke with the men who had distanced themselves from their familial roots to establish homes amidst agricultural lands or at a manageable distance from the main village, their responses were revealing and often pointed to a common refrain: “The women of the household always argued and fought among themselves, and the only solution was to create a separate space.” This perspective, while indicative of male viewpoints, raised important questions about the underlying dynamics at play. It suggested that the tensions within households were not just personal grievances but were rooted in larger social structures and expectations.

Intrigued by this narrative, I sought the perspectives of the women who accompanied their husbands in founding these new hamlets. Their narratives were rich and multifaceted, often revealing the complexities of household interactions that are typically overlooked by scholars. Notably, their responses were more process-oriented and detailed, albeit varied and sometimes contradictory, reflecting the deep realities of their daily lives.

From discussions with these women, several recurring themes emerged. For instance, many recall a time when family life was harmonious, particularly when only the elder son was married. During this period, the household operated smoothly, with clear roles and responsibilities. However, as younger brothers married and established their own families, the physical and emotional space within the household began to shrink, leading to increased tensions and competition for resources.

Conflicts often stemmed from underlying social hierarchies, with women from lower castes, those with unemployed husbands, or those who were orphaned frequently being targeted and blamed. Interestingly, the victim women expressed their frustrations through double-edged phrases

Reflecting on my old diaries, I recalled a particularly insightful conversation with a group of elder women from the Khairpur Mir’s district. They were the partners of husbands who had established a segregated hamlet on abandoned land—a decision born out of necessity rather than a mere desire for independence. Their stories highlighted how household work is interwoven and plays a significant role in family dynamics. They told that delays in household tasks—such as cleaning, washing dishes, milking buffaloes or cows, and preparing meals—became contentious issues among the women. Each woman had her own priorities, often overlooking the interconnectedness of these tasks. For instance, the timely preparation of breakfast depended on the previous night’s dishwashing activity. When tasks were not completed efficiently, it created a domino effect, leading to frustration and blame.

I was surprised to learn that some women employed delay tactics as a form of subtle revenge, creating awkward situations for others and exacerbating tensions. Conflicts often stemmed from underlying social hierarchies, with women from lower castes, those with unemployed husbands, or those who were orphaned frequently being targeted and blamed. Interestingly, the victim women expressed their frustrations through double-edged phrases, often intended to be overheard by their adversaries. Sentences like “Asan Ghareeban Te Sabhn Ji Kawarr Aa” (We poor folks bear the brunt), “Wazan Sedhi Kathe te Pawando Aa” (A straight wooden plank bears more weight), “Huje ko Wali Waris ta Asa Bhe Sat Surey’n Budhayoon” (I could rebuke them, but I have neither support nor a promoter), and “Sabhen Ji Kawarr ghareeb te” (Everyone shows anger at the poor) these monologues encapsulate feelings of victimized while simultaneously inviting sympathy or acknowledgment from others. However, such expressions rarely sparked constructive dialogue, as discussions about tensions seldom moved beyond domestic confines. Ultimately, these frustrated voices reached the ears of the mother-in-law, who believed that addressing these issues would disturb family harmony. Consequently, grievances were often silenced, as she feared that acknowledging them would upset her sons or invite gossip from the neighbours.

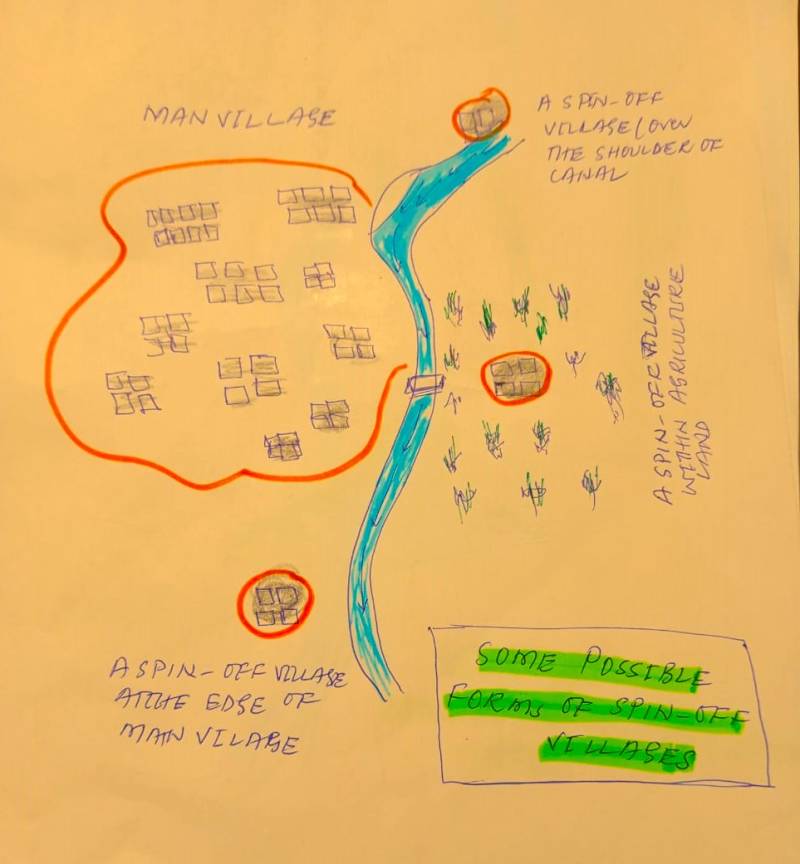

Despite these challenges, families continued to grow. However, unresolved tensions seeped into the brothers’ ears, where each wife interpreted familial disputes through her own lens. Miscommunication flourished: one brother perceived that his siblings are unsupportive, while another believed that he contributed more toward collective resources yet received less in return. This pervasive sense of inequity further fuelled resentment and discord among the brothers. Ultimately, a more industrious brother often emerged as a catalyst for change (separation), leading to the decision to spin off from the family. Initially, discussions about these issues took place in private, fostering the conditions necessary for the establishment of a new hamlet. Factors such as available land—whether at the village’s edge, in nearby fields, or along the watercourses—plays a crucial role, as did the absence of objections from local authorities, landlords, or family patriarchs.

In addition to these factors, other reasons for separation also exist. One of my old notebooks contains findings from a mini-workshop held at Ustad Khadim Talpur’s Otaq-cum-library in Talpur Wada (Taluka Kotdiji, Khairpur Mirs). During this workshop, we—Ashique Solangi, Nazir Ujjan, Jabbar Khaskhelly, Ustad Soomar Buriro, Ustad Khadim Talpur, and I—brainstormed and listed common reasons for the splitting of joint families and the subsequent establishment of new tiny villages or hamlets. We all agreed that families’ coherence or separation is shaped by their own realities and perspectives. However, we were agreed that are various reasons.

My notebook from those days detailed these reasons: conflict and tensions arising from frequent disagreements; marital strain due to siblings' marriages changing household dynamics; disparities in earning and resource allocation; cultural and social pressures to conform to traditional roles; the desire for independence as individuals grow; economic factors leading to new opportunities and employment; gender dynamics where male expectations placed on women clash with women’s aspirations; the absence of support systems—emotional, financial, or social—during adverse situations; emotional abuse manifesting as persistent criticism, manipulation, or targeted gossip; financial exploitation by family members who take advantage of others’ contributions; neglect of responsibilities by those who consistently fail to uphold their duties; cultural oppression through the imposition of rigid cultural or religious practices; betrayal and disloyalty stemming from infidelity that compromises family honour; differences in parenting styles leading to disagreements; interference from extended family members; substance abuse issues affecting a family member; mental health where an individual doesn’t receives adequate support; and long-standing unresolved grievances. I still remember, and my notebook entries confirm, that by the end of our discussions, we all agreed that injustice within families can take many forms. The cumulative effect of these unaddressed issues can push individuals to seek separation or establish a new home or hamlet. However, we also recognized that the decision to separate is often a response to a deep-seated desire for safety, respect, and personal fulfilment in one's life.

The social dynamics of decision-making within a newly established hamlet often rest solely with the elder, reflecting traditional hierarchies and cultural norms. Allow me to illustrate this with an example from my experience working as a social organizer for a development organization. My friend, Abid Chana, and I were tasked with introducing our organization’s programs to various villages. After some exploration, we discovered a small hamlet. Upon our arrival, we were greeted by a resident who inquired about the purpose of our visit. We explained our mission and outlined the potential benefits of our program. After about fifteen minutes of discussion, he paused and said, ‘Let me call Ada Wdo’ (elder brother). He then left to fetch an old brother. Upon his return, we recounted our presentation, reiterating the program’s objectives and advantages. When we finished, we sought the elder’s thoughts. He acknowledged that the program appeared beneficial but informed us that we would need to return the following day. His reasoning was clear: the decision regarding whether the hamlet would collaborate with the organization rested solely with Babo (father) he was not present at the time.

This interaction shows the importance of traditional authority structures in newly formed tiny village/ hamlet. In many such settings, the elder not only serves as a decision-maker but also as a custodian of cultural values and norms. Their authority is often respected and unquestioned, reflecting a deep-seated belief in the wisdom that comes with age and experience. In essence, the elder’s role in decision-making within the hamlet is emblematic of broader societal structures that prioritize collective consensus and respect for authority.

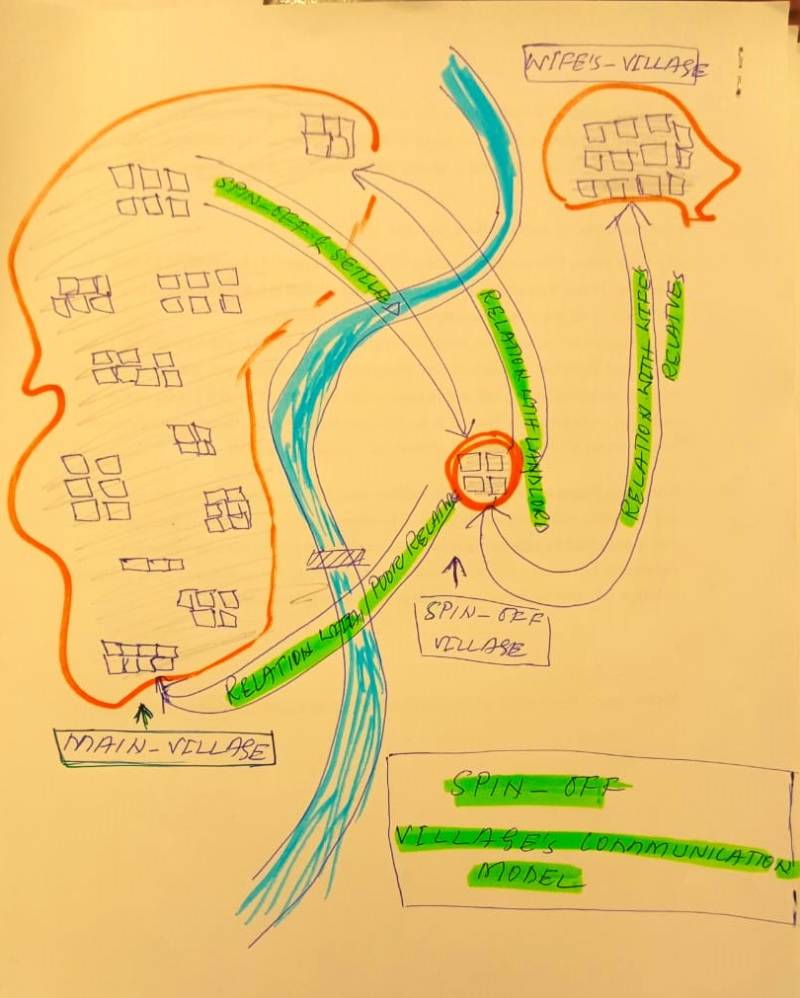

The communication between a newly established tiny village or hamlet, and family members residing in the main village is largely influenced by the reasons behind the separation. When the establishment of a new hamlet stems from issues of betrayal and disloyalty, such as infidelity, communication between the two groups tends to be severely limited. In these cases, the emotional fallout creates barriers that hinder interactions and foster estrangement.

Understanding the communication dynamics of these spin-off villages is a compelling topic within the fields of sociology and anthropology. In contrast to situations marked by betrayal, family members from the new hamlet often maintain connections with their relatives rather than family members. If, for example, the wife of the individual who founded the hamlet comes from a different caste or village—especially if that village is in close proximity—communication between the two families is likely to be frequent. This interconnectedness reflects the fluid social networks that can exist even amid separation.

Despite its status as an independent unit, the newly established hamlet continues to engage with neighbouring hamlets and other communities from the main village. This engagement is significant as it allows for the preservation of social ties and cultural continuity. Interestingly, the head of the new hamlet may still visit the landlord of the old village to address social issues or seek resolution to conflicts. This dynamic illustrates a deep relationship where the individual retains respect for traditional authority and acknowledges the existing power structures of the main village. In fact, these villages serve as microcosms of family complexities, where personal grievances can lead to social change and the formation of new villages/ hamlets. Ultimately, the dynamics of Pahenja Ghar demonstrate the resilience and adaptability of its inhabitants, symbolizing both change and enduring connections that enrich the social fabric of the rural area.