In most South Asian literature, ranging from pre-Mughal accounts to pre-Partition ones, Punjab figures as a land of ampleness and immense natural wealth. Folk tales and Punjabi literature are littered with accounts of romances, myths and legends emerging from the banks of its several large rivers. Heroes and heroines in these tales have crossed onto the other side of the banks to be reunited with their beloved after long struggles that involved suspicion, betrayal and elopement. That Punjab is synonymous with the land of plenty is no new fact, but with the changing times it risks becoming a land of scarcity; one not envisioned in the romantic literature of earlier periods.

Urbanisation has led to a vastly changing landscape. Green tracts of land are marred by brick kilns sprouting seemingly everywhere, which hope to meet the increasing demands of the construction industry. Lands where cattle once grazed have turned into drab and colourless sand banks. Lahore, at the heart of the province, is now home to over 10 million people.

As the majority of city dwellers cannot afford bottled water, their risk of contracting waterborne diseases is at 50% according to a study by the Punjab EPD

And in such a landscape, Pakistan faces impending water crises both in terms of scarcity and contamination.

In Pakistan, Karachi is considered to have the worst urban water scarcity problem. When asked whether the situation in Lahore has reached a similar critical level, Tauqeer Ahmad Qureshi, Director Implementation at the Punjab Environment Protection Department states: “The problem of water contamination in Lahore has exceeded critical levels. This is clear from the increased purchase of bottled water; anyone who can afford it has switched.”

As the majority of city dwellers cannot afford bottled water, their risk of contracting waterborne diseases is at 50% according to a study by the Punjab EPD.

In Lahore, the primary source of water is groundwater boring, which has depleted natural water aquifers to alarming levels; bringing down the ground water level by 2 feet annually. According to WWF Pakistan, all of Lahore’s water is supplied by 480 tube wells that extract water from a depth of 120 to 200 meters at an approximate amount of 160 million gallons per day.

Spokesperson from WASA Lahore Imtiaz Mujtaba Ghauri comments on how the impending crises go far beyond contamination – as there is widespread ignorance about the scarcity of water resources themselves. “Water is considered a cheap resource as tariffs have not increased since 2004. A monthly water bill is about Rs. 300. So, when compared to electricity, people take it for granted.” He further noted: “City government has ordered no standing water in the city. This means that most water is let out into the sewerage drains and clean rainwater is wasted. Urban planning has not taken into account how concrete roads and pavements do not allow for groundwater recharge when it rains.”

The sight of throngs of people jumping into the canal is as obvious today as it would have been many years ago, but it does not conceal that fact that there is a dangerous future to behold here. Owing to a lack of knowledge regarding scarcity, there is a prevalent callous attitude about water amongst city dwellers.

The Ravi

The river Ravi is of primary importance when examining the state of water resources in Lahore. The entire municipal waste from Lahore city is collected through a network of 14 main drains and discharged into the Ravi River without any treatment. As a result, according to a study by Environment Protection Department (EPD) Punjab, the Ravi river is now termed ‘biologically dead’ as it is devoid of dissolved oxygen along much of its 520 kilometre length. The areas it supports are some of the biggest economic centres of the country, including Lahore, Faisalabad and Sahiwal – whose industrial, agricultural and household waste are the main cause of its abysmal condition.

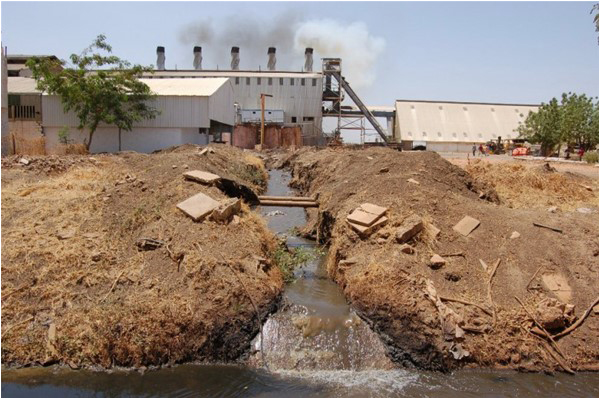

The practices employed at the countless industrial and agricultural stations in these cities are the main reason for water pollution in the Ravi today. According to a study by EPD, Punjab hosts over 48,000 industrial units, of which 90% are qualified as SMEs (Small and Medium Enterprises). The onus for treating their waste water is on the local governments as costs for such practices are exponential for small scale industries. Depending on where these enterprises are located, they are monitored by the Water and Sanitation Agencies (WASAs) or the District Government or Tehsil Municipal Administrations. However, none of the cities or towns in Punjab have sewerage treatment systems for their waste water. WASA Faisalabad is an exception as a reported 20 percent of its generated sewage is treated through water filtration plants created through collaboration with local stakeholders.

A fleeting sight of the Ravi as you enter Lahore is perhaps most illustrative of its severely polluted condition. Its width is light grey in colour and shows no evidence of agriculture that once thrived. It is lined instead with sandbanks and derelict lands that host brick kilns and small industries. Upstream and downstream on the outskirts of Lahore, the Ravi hosts sporadic farming land that little resembles that of days gone by. Cows munch on patches of grass while dark smoke bellows out of brick kilns alongside. Modern agricultural practices with excessive use of pesticides and fertilisers leach into groundwater and wash into the Ravi during the rainy season. In the dry season, with scarce glaciers melting and adding water to the river, the Ravi is considered a mere “dumping pit” for sewerage and a general depository of Lahore’s municipal waste.

Pollutants in the Ravi deteriorate the ground water quality in Lahore as they seep into the earth. This has led to an alarming increase in arsenic concentration in the ground water to 40-80 ppb; a critically high level by WHO standards. With water resources being essential to daily life, perhaps even more than electricity, the current government’s neglect for raising awareness and implementing policies will prove to be a major error in hindsight.

Recent Developments

The Centre for Water Infomatics and Technology Institute at LUMS (WIT-LUMS) has been involved in events and upcoming research regarding water sustainability in Lahore. They are involved in devising methods for water filtering in pilot projects which can be upscaled for commercial purposes. WIT-LUMS is important for creating a climate for alternative and goal-based thinking when it comes to managing water in Lahore.

Director WIT Dr. Abubakr Muhammad, explains how WIT is helping to bridge the gap between academia and industry on one hand, and academia and government on the other.

“The Centre works with important government institutions – including Pakistan Commission for Indus Waters, Punjab Irrigation Department and Planning and Development Department Punjab – to find efficient solutions to current water management issues using state-of-the-art technology. The Centre has also established industry affiliate programs in which it works with leading private sector entities such as Nestle-Pakistan and others to work towards minimising industrial and on-farm water footprints and introduce precision agriculture technologies within their farmer networks.”

With alternative practices, problem-solving methodologies, and effective partnerships such as those devised at WIT-LUMS, the path for mitigating some of the existing threats to water in Punjab could be viable.

But all of this can only happen once the authorities and the general public begin to fathom the scale of the crisis that we face.