The last couple of years have brought about a resurgence of the debate on race, caste distinctions and slavery within the US. Like colonialism or apartheid, just because a system has been legally abolished does not mean it stops existing. It takes centuries to recognize the trauma and to process its effects – and that, in turn, affects societies as a whole.

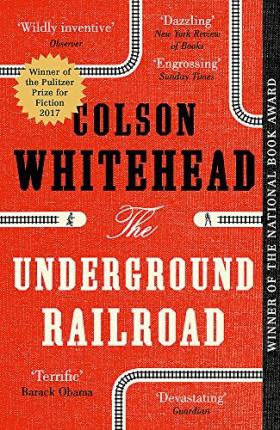

Over the summer, I had been reading Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer-winning Underground Railroad and also watched the accompanying series that has just been released on Amazon Prime. It was partly to understand American history and also as a way to delve into a world that is so different from our own.

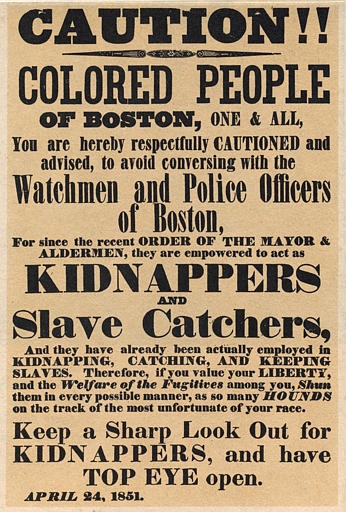

Story-telling is a unique way to confront otherwise difficult topics. Whitehead’s novel is a depiction of what existed in the Underground Railroad, an informal, loose network of abolitionists and safehouses that worked to help slaves escape from the horrors of their servitude. Whitehead’s version is a reconstruction of a metaphorical underground train that connects the US states. The timeline is set around 1850, coinciding with the Fugitive Slave Act, which sought to ensnare slaves that had run away. That led to a rise in bounty hunting across states as well as activity to help the underground effort. Each chapter showcases a different state and experience that slaves faced. The book is a depiction of what might have happened to African-Americans in the 1800s, rather than a narration of actual events.

Whitehead presents the network as an actual train, with underground stations staffed by activists serving to change the course of lives. This train network helps slaves who run away, moving north to freedom through various locations, states and characters.

Each station that Cora stops at shows a different aspect of racism and structural inequity. Though some of these are fantasy, they are based on real stories and historical anecdotes

Cora, the heroine of the book, is a young girl who escapes a plantation and life of servitude though time-space and her own struggle. During her journey, she is a witness to crime and horror – whether occasioned by segregation, violence or medical experimentation. She sees the unspeakable ways in which the African Americans were subjugated. At each station, an oral history is recorded which essentially serves as the history of their past, derived from real histories of famous slaves who had escaped successfully, such as Harriet Jacobs and Frederick Douglas. History documents that thousands of slaves did find their way to freedom, but almost 4 million men, women and children were still held in bondage at the beginning of the American Civil War in 1861.

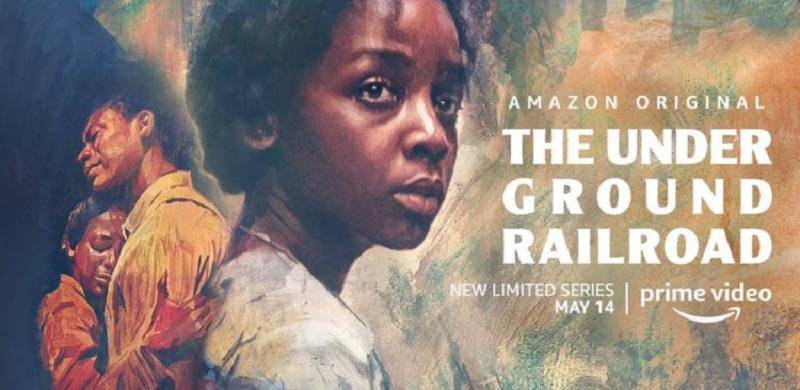

Barry Jenkins, the acclaimed director of the Oscar-winning film Moonlight chose to adapt Whitehead’s book for the screen – interspersing fiction with reality and created a spellbinding series of ten episodes. Each chapter is marked by mixing the old with the new, using contemporary rap and music by African-American musicians. Past and present are therefore one highlighting that some of the issues Cora faces are still unresolved in modern day America.

This series is not for the faint-hearted. Violence towards African-Americans is very graphic and disturbing. What is incredibly compelling, however, is the powerful narrative: the story of Cora’s struggle to be treated as human, aspire to a life of dignity and respect, to fulfil her desires and longings. It is a universal, timeless story.

The characters are not all black and white. Many are shown in a sympathetic light – the slave owner who traverses states to get Cora, or Caesar the handsome man that she runs away with when she begins her rail road adventure. The conductor gives her a taste of what is to come: “If you want to see what this nation is all about, I always say, you have to ride the rails. Look outside as you speed through, and you’ll find the true face of America.” Cora soon realises that this means darkness for mile after mile, state after state. Though she escapes places, she cannot escape her race or how she will be treated by others because of it. The illusion of a train to nowhere with no light at the end of the tunnel shows the hopeless struggle though she continues to rise and survive – despite it all.

This series is not for the faint-hearted

Each station that Cora stops at shows a different aspect of racism and structural inequity. Though some of these are fantasy, they are based on real stories and historical anecdotes. Caesar and Cora first escape from a Georgian plantation and alight into a fictional South Carolina world where blacks are actually treated fairly, given jobs and clothes. Here the world is an experimentation in cultural assimilation, where the future is seen through the urban dream of building skyscrapers and dignity for the workforce. It is only when Cora realises that there are no black children that Whitehead exposes the medical experiments and forced sterilization campaigns that were conducted on slaves, without their knowledge.

Each station that Cora stops at shows a different aspect of racism and structural inequity. Though some of these are fantasy, they are based on real stories and historical anecdotes. Caesar and Cora first escape from a Georgian plantation and alight into a fictional South Carolina world where blacks are actually treated fairly, given jobs and clothes. Here the world is an experimentation in cultural assimilation, where the future is seen through the urban dream of building skyscrapers and dignity for the workforce. It is only when Cora realises that there are no black children that Whitehead exposes the medical experiments and forced sterilization campaigns that were conducted on slaves, without their knowledge.

She then flees to North Carolina – a state which is being built on the principles of white supremacy, where slavery is not only outlawed but also its practice. In his book, Whitehead in his own words wanted to show the “truth of things, not facts.” Rather like Arthur Haley’s epic Roots, Whitehead’s work presents fictional characters facing fictional circumstances. In fact, each aspect of the systemic racism he writes about was a facet of the truth of African-American history. History merges between the past and present, with events that happened during the 1800s taking place through Cora’s eyes as the conductor of this virtual train.

Many of the issues that Cora confronts are still topical – caste divisions, rank racism, violence towards women, colonialist elitism, discrimination. Each is premised on the dehumanisation of others. It is fitting that much of the power of the series lies in the expressive eyes of the young South African actress, Thuso Mbedu. Her eyes speak to the horrors of what confronts her, yet like every tragic figure she remains human: when choosing to run after seeing a slave being burnt to death, during her harrowing journeys, or the suffering of living (like Anne Frank) in an attic for months on end. She never loses her humanity even though her experiences are traumatic and inhumane.

Story-telling can be the most powerful way to understand how others live. We are often reminded that those who forget history are condemned to relive it and that is the most gripping lesson that this novel and its series of stories teach us.

Whitehead’s novel is a reminder that the end of slavery does not mean the end of racism. The abolition of race laws does not prevent attacks upon a community. The past is repeated somewhere and everywhere across the globe.