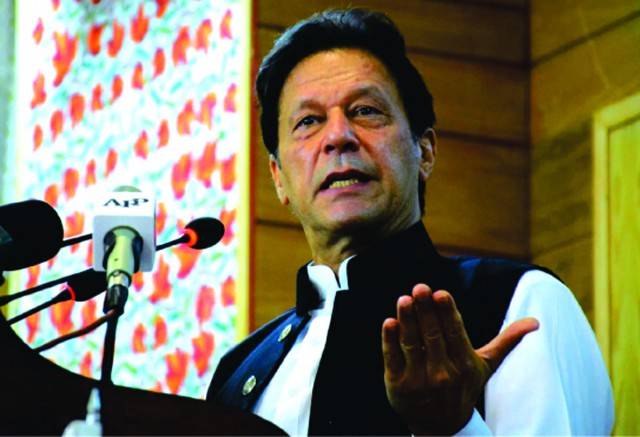

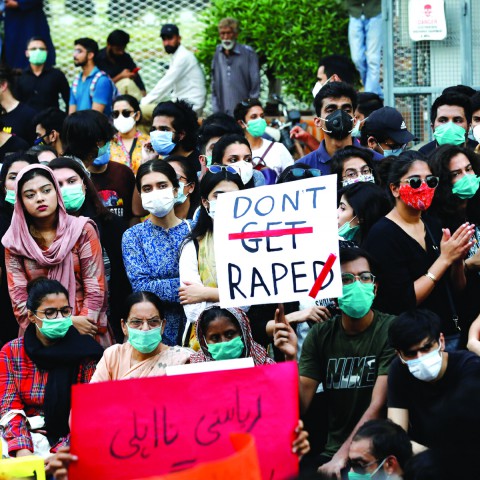

The Economic Times, the New York Times, Al Jazeera, Sky News, The Indian Express, Gulf News, The Business Standard, The Telegraph, CBS, the Daily Mail, BBC and the Hindu Times reported that during his public question-and-answer session on national TV, Imran Khan, the Prime Minister of Pakistan, victim-blamed an entire generation of Pakistanis regarding rape culture.

The international outbreak – that wrecked more havoc on my Twitter than my home – made me curious as to what Khan really said in his causal Sunday Q&A.

Seemingly, Arshad Khan from Latifabad, Hyderabad, had asked Khan about his government’s policies and actions regarding the rise in rape cases throughout Pakistan.

While answering his question, Khan made citizens aware of the newly revised Rape Ordinance that was passed last December, which aims to create a national sex offenders register, protect the identity of the survivor and allow chemical castration as a punishment to some extent. Khan also made sure to reiterate how exceedingly common yet under-reported rape cases have become due to the cultural taboo surrounding sexual violence in Pakistan. Citing the nature of corruption, Khan emphasized how rape, too, due to laws prohibiting it, has become a major offence. Hence, he called on Pakistani citizens to come together and make changes within their public sphere to eradicate this crime. By calling out media channels and production houses that use a male’s gaze to depict women’s bodies, Khan urged the country to put a stop to an increasingly Westernized understanding of liberation.

Now, Khan’s words that have caused anger within the national and diaspora Pakistani community stem from this particular unanimous calling that urges Pakistanis to stop ‘fahaashi’ (vulgarity) and adopt ‘pardah’ (concealment). Culturally and linguistically, the two practices and words: ‘fahaashi’ and ‘pardah,’ have been associated with women in Pakistan. Although Khan did not point to women or blame them in the sort of singular way that he was once accustomed to expressing, he did linguistically make a remark that pointed to women having – if not equal – some hand in provoking the rapist, while not once mentioning the responsibility of the state that is incumbent in harbouring, creating and manifesting an attitude that promotes rape culture. It may have been Khan’s aim to call out the entire nation and, more so, even men creating and consuming sexualized media. However, his choice of language – given the context – quite brutally targeted the female body, that has time and again been blamed for the violence it has endured.

What the international media lacks in their reportage of this incident is Khan’s silence on naming the rapist who commits the crime as a predator, a violent perpetrator and a threat to Pakistanis. By contouring the entire conversation into a sermon for the nation, Khan’s first failure becomes his inability to recognize the criminal.

During the conversation, Khan also turns a blind eye to the entire issue of trans and male rape, which is not only ignorant, but also dangerous to the fabric of this nation. His negligence to recognise rape as a crime that is equally incurred by men not only disassociates them from the conversation, rather depicts them as felons and grievers. They are either beasts who are only capable of carrying out these crimes or fathers and brothers who mourn their women-folk’s violated bodies. By failing to mention how men are also prone to sexual abuse, Khan’s dialogue further distances men from accessing this conversation as healers and survivors. Regarding trans-folk, who suffer rape most silently, this exchange not only diminishes their already marginalized position in our society but also pushes them out of the narrative.

The distance created from these gendered conversations within our communities has been boding ill for our nation and will only worsen if we and our political leaders discuss sexual violence as a feminine issue that emasculates men and is limited to heterosexual relationships. More importantly, it makes it harder for us to find solutions as Pakistanis who share a common loss of safety and security within our country, our home. The gendering of this conversation makes it harder for us to find a common ground because we begin aligning with our politically designated roles.

Imran Khan might have meant to call on the nation, as he most promisingly does in everything that the state should take direct action for, but he evidently got called out. I believe he should be, but not entirely for his political language, rather for his silence and his failure to recognize every facet of one of the fastest growing national issues. Consequently, as Pakistani, we should be mindful about the conversations that we have about rape. We cannot just think about its repercussions and dangers for young women. We have to think about the boys, men, old men, old women, hermaphrodites and trans folk who are affected just as much.

Here the numbers may not tell the full story. Statistical data collections are carried out by people who have access to people who can talk to people. They are many who can’t.

The international outbreak – that wrecked more havoc on my Twitter than my home – made me curious as to what Khan really said in his causal Sunday Q&A.

Seemingly, Arshad Khan from Latifabad, Hyderabad, had asked Khan about his government’s policies and actions regarding the rise in rape cases throughout Pakistan.

While answering his question, Khan made citizens aware of the newly revised Rape Ordinance that was passed last December, which aims to create a national sex offenders register, protect the identity of the survivor and allow chemical castration as a punishment to some extent. Khan also made sure to reiterate how exceedingly common yet under-reported rape cases have become due to the cultural taboo surrounding sexual violence in Pakistan. Citing the nature of corruption, Khan emphasized how rape, too, due to laws prohibiting it, has become a major offence. Hence, he called on Pakistani citizens to come together and make changes within their public sphere to eradicate this crime. By calling out media channels and production houses that use a male’s gaze to depict women’s bodies, Khan urged the country to put a stop to an increasingly Westernized understanding of liberation.

Now, Khan’s words that have caused anger within the national and diaspora Pakistani community stem from this particular unanimous calling that urges Pakistanis to stop ‘fahaashi’ (vulgarity) and adopt ‘pardah’ (concealment). Culturally and linguistically, the two practices and words: ‘fahaashi’ and ‘pardah,’ have been associated with women in Pakistan. Although Khan did not point to women or blame them in the sort of singular way that he was once accustomed to expressing, he did linguistically make a remark that pointed to women having – if not equal – some hand in provoking the rapist, while not once mentioning the responsibility of the state that is incumbent in harbouring, creating and manifesting an attitude that promotes rape culture. It may have been Khan’s aim to call out the entire nation and, more so, even men creating and consuming sexualized media. However, his choice of language – given the context – quite brutally targeted the female body, that has time and again been blamed for the violence it has endured.

It may have been Khan’s aim to call out the entire nation and, more so, even men creating and consuming sexualized media. However, his choice of language – given the context – quite brutally targeted the female body, that has time and again been blamed for the violence it has endured

What the international media lacks in their reportage of this incident is Khan’s silence on naming the rapist who commits the crime as a predator, a violent perpetrator and a threat to Pakistanis. By contouring the entire conversation into a sermon for the nation, Khan’s first failure becomes his inability to recognize the criminal.

During the conversation, Khan also turns a blind eye to the entire issue of trans and male rape, which is not only ignorant, but also dangerous to the fabric of this nation. His negligence to recognise rape as a crime that is equally incurred by men not only disassociates them from the conversation, rather depicts them as felons and grievers. They are either beasts who are only capable of carrying out these crimes or fathers and brothers who mourn their women-folk’s violated bodies. By failing to mention how men are also prone to sexual abuse, Khan’s dialogue further distances men from accessing this conversation as healers and survivors. Regarding trans-folk, who suffer rape most silently, this exchange not only diminishes their already marginalized position in our society but also pushes them out of the narrative.

The distance created from these gendered conversations within our communities has been boding ill for our nation and will only worsen if we and our political leaders discuss sexual violence as a feminine issue that emasculates men and is limited to heterosexual relationships. More importantly, it makes it harder for us to find solutions as Pakistanis who share a common loss of safety and security within our country, our home. The gendering of this conversation makes it harder for us to find a common ground because we begin aligning with our politically designated roles.

Imran Khan might have meant to call on the nation, as he most promisingly does in everything that the state should take direct action for, but he evidently got called out. I believe he should be, but not entirely for his political language, rather for his silence and his failure to recognize every facet of one of the fastest growing national issues. Consequently, as Pakistani, we should be mindful about the conversations that we have about rape. We cannot just think about its repercussions and dangers for young women. We have to think about the boys, men, old men, old women, hermaphrodites and trans folk who are affected just as much.

Here the numbers may not tell the full story. Statistical data collections are carried out by people who have access to people who can talk to people. They are many who can’t.