Since I wrote my last article, President-elect Donald Trump has continued to make headlines which either frightened half of the US population, or caused it to snicker out loud. The other half of the US voting public appeared to remain comfortable with their strongman-elect. The headlines mainly concerned foreign relations either directly or indirectly. The news was generated by either telephone conversations he had with foreign leaders, his constant tweeting or from his defensive tweeting after a scary or humorous telephone conversation with a foreign leader.

Let’s start with what may be the most humorous episode of the transition: the conversation he is alleged to have had with the prime minister of Pakistan. I have to be careful with this because the only readout we have is from the Pakistani Ministry of Information. It published what appears to be a near verbatim transcript of the conversation, in which Trump was apparently effusive in his praise of Sharif and Pakistan. Trump headquarters has been mum. I have to rely on a column by Dana Milbank in the Washington Post, who reasoned that not only did it read like an authentic record of the talk, but given the lack of any push back from the Trump camp it must be so. Milbank notes that the conversation, as it was reported, contradicted a Trump campaign representative visiting India a few days earlier who promised the new administration would seek to have Pakistan named a state sponsor of terror. But the humorous part is the fantasy conversations Milbank constructs between Trump and other world leaders, in all of which he has Trump saying what a particular leader would most wish to hear, followed with a conversation with another world leader saying exactly what that leader would wish to hear, but which directly contradicts what he had said to the previous leader. Milbank’s imaginary conversations were hilarious, but also scary to many Americans who worry that the pattern is more real than imaginary, and we see in it the makings of a major, perhaps irreparable loss, in US international credibility.

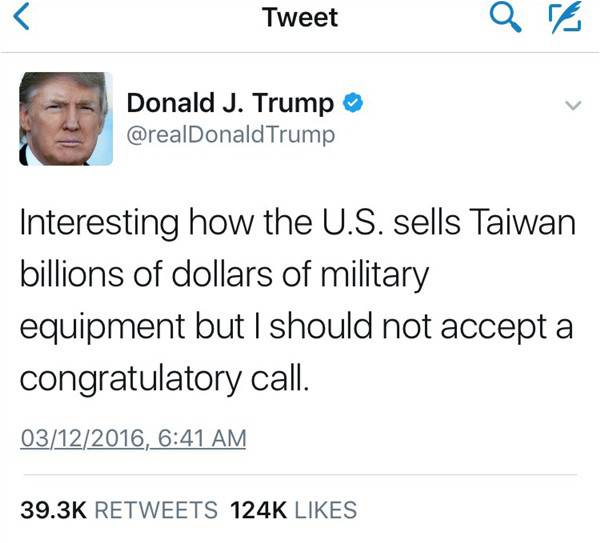

Of course, the major uproar was over the phone conversation Trump had with the president of Taiwan. It was not clear in the first few days of the aftermath of that call whether Trump accepted it without understanding the 40-year-old thick pattern of diplomatic protocol that overlay US relations with Taiwan. These were worked out at the start of the Nixon Administration (by Henry Kissinger) and were seen through then by the Carter Administration to enable the US to have an active and fruitful relationship with Taiwan, thought to be a domestic political imperative at the time, and a full diplomatic and political relationship with China. A US president hasn’t spoken to a president of Taiwan in this public context since 1979. If Trump took the call out of ignorance, it would reflect a problem as large as, if not larger than, him knowing what he was doing.

Most experts now believe it was deliberate, a planned charade to signal to China that he means what he says about being tougher toward its trade, investment, intellectual property, and currency policies. While some people may exhale with relief that Trump acted deliberately, not out of ignorance, many China experts believe his act is just another kind of ignorance. China reacted in a very low-key professional manner, without the bombastic rhetoric which it often resorts to, but it sought to drive home the fact that it had ways of retaliating that Trump may not have thought of. They joined Russia in the Security Council to veto the resolution for a temporary humanitarian ceasefire in Aleppo (we now have the Syrian victims of a continued Russian and Assad government assault on our conscience—if only because Assad and Putin do not have consciences), and they are withholding cooperation on North Korea. While Chinese policies on some of the issues that concern Trump do impact the US economy, his complaint on trade is largely misplaced. And in particular, his charge that China is a currency manipulator is passé. China has let it currency drift down over several years to what may be a market rate, and then put a floor under it so it would not go much lower. That seems to have changed as the floor is, I am told, removed. In other words, China is preparing for a trade war.

In general, contradiction is the core of Trump’s foreign policy, as he described it (vaguely I admit) during the campaign. Of course this may be deliberate, as he said often that he would rely on unpredictability as his main principle of foreign policy. But unpredictability is not the same as contradiction, and to others, his policy pronouncements look to be contradictory and predictably counterproductive, as well as not thought through.

In the Middle East, he is constantly insisting that his administration will “stand up” to the Iranian regime and tear up the nuclear agreement with Iran. At the same time, he appears to want to let the Assad regime and the Russians do their dirty work in Syria and gain a military victory in that vicious civil war, which helps Iran accomplish its goals in the Middle East. His anti-Muslim feelings and pronouncements will undermine US relations with the Muslim world and alienate American Muslims, which will aggravate the struggle against terrorism around the world. It will, inter alia, feed the jihadist narrative and probably increase the flow of young Muslims toward extremist groups; I have seen at least one expert on terrorism predict that this will result in a major terrorist strike in the US in 2017. Worse still, this anti-Muslim rhetoric gives the extremists even more incentive to carry out a domestic attack, as it would cause the administration to elevate the anti-Muslim rhetoric, and perhaps even take anti-Muslim measures, which ISIS and Al Qaeda would dearly love to see happen. And none of this will be helped by Trump’s decided leaning toward Russia, despite its egregious aggression against Ukraine, threats to the Baltic states, and the bitter disappointments of two serious attempts by two presidents (Bush and Obama) to “reset” relations with Putin and the Russians.

The list of names added to Trump’s cabinet gives no reason to hope that these policies will somehow be put aside as simple campaign rhetoric and that more pragmatic and fact-driven policies will be adopted. As this was written, the leading contender for Secretary of State was said to be Rex Tillerson, the CEO of Exxon, who for 30 years has been “doing deals” with the Russians and is a buddy of Putin. (He has since been nominated). He has no government or diplomatic experience, which seems to be a common characteristic of Trump’s cabinet. And he has named to several cabinet posts men and one woman who are devoted to the abolition of the agencies they will be in charge of.

In fact, it is clear that with a willing Republican Congress, this Trump Administration could turn the US radically to the right in the next four years. Ironically, Ronald Reagan came to the presidency in 1980 having won 489 electoral votes with a popular vote majority over 13 million, promising less government and, he left office in 1988 with a government larger than he found it. Trump lost the popular vote by about 2.7 million votes, but won 306 electoral votes because he won three mid-western states by 140,000 more votes than Ms. Clinton. He won the election because of 0.0333 of the popular vote in three depressed states, and yet he seems determined to turn the country in a very different direction. The Republican Congress just can’t wait to get started on its “revolution,” bugger the foreign policy consequences as well as the lack of mandate.

The author is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC, and a former US diplomat who was Ambassador to Pakistan and Bangladesh

Let’s start with what may be the most humorous episode of the transition: the conversation he is alleged to have had with the prime minister of Pakistan. I have to be careful with this because the only readout we have is from the Pakistani Ministry of Information. It published what appears to be a near verbatim transcript of the conversation, in which Trump was apparently effusive in his praise of Sharif and Pakistan. Trump headquarters has been mum. I have to rely on a column by Dana Milbank in the Washington Post, who reasoned that not only did it read like an authentic record of the talk, but given the lack of any push back from the Trump camp it must be so. Milbank notes that the conversation, as it was reported, contradicted a Trump campaign representative visiting India a few days earlier who promised the new administration would seek to have Pakistan named a state sponsor of terror. But the humorous part is the fantasy conversations Milbank constructs between Trump and other world leaders, in all of which he has Trump saying what a particular leader would most wish to hear, followed with a conversation with another world leader saying exactly what that leader would wish to hear, but which directly contradicts what he had said to the previous leader. Milbank’s imaginary conversations were hilarious, but also scary to many Americans who worry that the pattern is more real than imaginary, and we see in it the makings of a major, perhaps irreparable loss, in US international credibility.

Contradiction is the core of Trump's foreign policy, as he described it during the campaign. This may be deliberate, as he said often that he would rely on unpredictability as his main principle of foreign policy. But unpredictability is not the same as contradiction, and to others, his policy pronouncements look to be contradictory and predictably counterproductive, as well as not thought through

Of course, the major uproar was over the phone conversation Trump had with the president of Taiwan. It was not clear in the first few days of the aftermath of that call whether Trump accepted it without understanding the 40-year-old thick pattern of diplomatic protocol that overlay US relations with Taiwan. These were worked out at the start of the Nixon Administration (by Henry Kissinger) and were seen through then by the Carter Administration to enable the US to have an active and fruitful relationship with Taiwan, thought to be a domestic political imperative at the time, and a full diplomatic and political relationship with China. A US president hasn’t spoken to a president of Taiwan in this public context since 1979. If Trump took the call out of ignorance, it would reflect a problem as large as, if not larger than, him knowing what he was doing.

Most experts now believe it was deliberate, a planned charade to signal to China that he means what he says about being tougher toward its trade, investment, intellectual property, and currency policies. While some people may exhale with relief that Trump acted deliberately, not out of ignorance, many China experts believe his act is just another kind of ignorance. China reacted in a very low-key professional manner, without the bombastic rhetoric which it often resorts to, but it sought to drive home the fact that it had ways of retaliating that Trump may not have thought of. They joined Russia in the Security Council to veto the resolution for a temporary humanitarian ceasefire in Aleppo (we now have the Syrian victims of a continued Russian and Assad government assault on our conscience—if only because Assad and Putin do not have consciences), and they are withholding cooperation on North Korea. While Chinese policies on some of the issues that concern Trump do impact the US economy, his complaint on trade is largely misplaced. And in particular, his charge that China is a currency manipulator is passé. China has let it currency drift down over several years to what may be a market rate, and then put a floor under it so it would not go much lower. That seems to have changed as the floor is, I am told, removed. In other words, China is preparing for a trade war.

In general, contradiction is the core of Trump’s foreign policy, as he described it (vaguely I admit) during the campaign. Of course this may be deliberate, as he said often that he would rely on unpredictability as his main principle of foreign policy. But unpredictability is not the same as contradiction, and to others, his policy pronouncements look to be contradictory and predictably counterproductive, as well as not thought through.

In the Middle East, he is constantly insisting that his administration will “stand up” to the Iranian regime and tear up the nuclear agreement with Iran. At the same time, he appears to want to let the Assad regime and the Russians do their dirty work in Syria and gain a military victory in that vicious civil war, which helps Iran accomplish its goals in the Middle East. His anti-Muslim feelings and pronouncements will undermine US relations with the Muslim world and alienate American Muslims, which will aggravate the struggle against terrorism around the world. It will, inter alia, feed the jihadist narrative and probably increase the flow of young Muslims toward extremist groups; I have seen at least one expert on terrorism predict that this will result in a major terrorist strike in the US in 2017. Worse still, this anti-Muslim rhetoric gives the extremists even more incentive to carry out a domestic attack, as it would cause the administration to elevate the anti-Muslim rhetoric, and perhaps even take anti-Muslim measures, which ISIS and Al Qaeda would dearly love to see happen. And none of this will be helped by Trump’s decided leaning toward Russia, despite its egregious aggression against Ukraine, threats to the Baltic states, and the bitter disappointments of two serious attempts by two presidents (Bush and Obama) to “reset” relations with Putin and the Russians.

The list of names added to Trump’s cabinet gives no reason to hope that these policies will somehow be put aside as simple campaign rhetoric and that more pragmatic and fact-driven policies will be adopted. As this was written, the leading contender for Secretary of State was said to be Rex Tillerson, the CEO of Exxon, who for 30 years has been “doing deals” with the Russians and is a buddy of Putin. (He has since been nominated). He has no government or diplomatic experience, which seems to be a common characteristic of Trump’s cabinet. And he has named to several cabinet posts men and one woman who are devoted to the abolition of the agencies they will be in charge of.

In fact, it is clear that with a willing Republican Congress, this Trump Administration could turn the US radically to the right in the next four years. Ironically, Ronald Reagan came to the presidency in 1980 having won 489 electoral votes with a popular vote majority over 13 million, promising less government and, he left office in 1988 with a government larger than he found it. Trump lost the popular vote by about 2.7 million votes, but won 306 electoral votes because he won three mid-western states by 140,000 more votes than Ms. Clinton. He won the election because of 0.0333 of the popular vote in three depressed states, and yet he seems determined to turn the country in a very different direction. The Republican Congress just can’t wait to get started on its “revolution,” bugger the foreign policy consequences as well as the lack of mandate.

The author is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC, and a former US diplomat who was Ambassador to Pakistan and Bangladesh