John Butt is an Englishman who arrived in Pakistan in the 1970s, working and living in the Pakhtun regions. John learned Pashto by asking people words that he did not understand. Working on a farm with a demanding workload, scrutinised by the farm owner, John complained to a fellow farm hand, who said “Babji der Zalim Saray de” (the landowner, Babji is a cruel man). John did not know the meaning of the word Zalim. Therefore John asked the landowner’s relative:

“‘Who did you hear it from?’ he asked. I told him Faqir Mohammad had called Babji a zalim saray. ‘It means cruel,’ Majeed’s brother replied, clearly not best pleased with Faqir Mohammad, effectively his family’s servant.”

John’s example shows how some effort to learn can pay dividends in picking up fluency in a language.

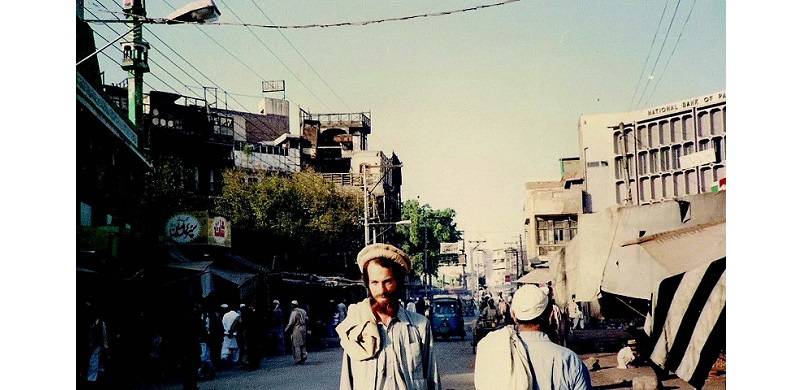

He embraced Islam in Swat after being touched by the generosity of a fellow traveller on a coach during Ramazan, who bought him some Iftari. John was impressed by the dynamism and confidence of the people of the Swat Valley, who were proud of their values and promoted Islam amongst Westerners who arrived there on the hippie trail. The tradition in Swat was that when a Westerner embraced Islam, they would be paraded down the main bazaar and everyone would offer them gifts of money. Butt tells us of another Briton who converted to Islam in Swat and this convert later established a mosque with mainly British Sufi converts in Norwich.

In 1974, Mr. Butt spent “considerable time in jail in Kabul, in reprisal for the suggested role of the British in the fall of Amir Amanullah himself. It is not history that has become the baggage in Afghanistan, it is people’s false and fanciful notion of history. For Pashtoons, Amanullah has become the hero. For Tajiks, Habibullah Kalakani is the one they look up to. In fact there were both Tajiks and Pashtoons who supported Amanullah in his modernising reforms in the country, just as there were huge and eventually dominant forces of reaction amongst both ethnic groups that either caused or benefitted from Amanullah Khan’s downfall. One only has to look at the edicts issued by Habibullah as king in Kabul. They were remarkably similar to the writ of the Taliban more than six decades later. The only difference was that Habibullah was a Tajik, the Taliban were Pashtoon. The difference is not ideological but ethnic.”

Butt further writes, “If there is a clash of ideas, one can discuss things, come to some accommodation and take things forward. If differences are interpreted as ethnic, then they become fixed, with no give or take. That is what has happened in Afghanistan. In 1974, amongst the nascent progressive, left-wing forces that wrested control in the new government of Daud Khan, the prevalent thinking was that Amanullah Khan had been deposed by an unholy alliance of the British and the mullas. Who better to blame than me: English and a mulla rolled into one?“

“I am indebted to the fast-talking lean-looking Ghulam Rasool. He was serving in the Ministry of Interior when I was taken there from Jalalabad […] He explained to me the reason for the antipathy amongst Afghan progressives to mullas, in particular why they were especially allergic to English mullas, in other words me. .Later others were to give me one famous example […] of a so-called English spy who came to serve in the Pul-e Khisti mosque in the centre of Kabul. I was told how he had led the prayers there for eighteen years. His purpose, so I was told was to topple Amir Amanullah Khan. Once (he) had achieved, in 1929, so the story goes, he returned to Great Britain, famously writing a letter to his congregation that they would have to say their prayers of eighteen years again, since he had been a British spy all along.”

John provides interesting anecdotes on what Afghans thought of their ‘national hero’:

“Amanulah Khan, hailed as a hero by the progressive, nationalist, more secular lobby of Pashtoon society, vilified by the more conservative, religious sections of society is arguably the most divisive figure in modern Afghan history. Progressive Pashtoon nationalists like Ghulam Rasool in the Ministry of Interior glorified him. On the other hand, I heard one maulvi I was in jail with say, probably too loudly for his own good: “Screw the wife of whoever calls him a ghazi (a holy warrior)!”

Butt expresses the view that, “It was in the time of Amanullah Khan that the fault lines emerged in Pashtoon society with progressives on one side, conservatives on the other, Pashtoon society has been grappling unsuccessfully with this division ever since.”

However, it is open to question whether any politician in the region has been ‘progressive’ during the twentieth century since otherwise Pashtun society would not be in the mess it is today.

Butt continues “Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan […] the leading Pashtoon nationalist […] is one who glorifies the role of Amanullah Khan and talks in his book, My Life and Struggle (Zama Jhwand au Jadd o-Jahd), about how the Pashtoons were united in joining their campaign in support of Amanullah Kahn. “There have been many kings of the Afghans he writes but they did not hold any of them so dear as they did Amanullah Khan”. That may have been true of the Pashtoons with whom Ghaffar Khan was associated. However it was also true that a good number of the Pashtoon tribes responded to the cry of their ulema and rose up against Amanullah Khan.”

The author describes a cleavage in Pashtun society between nationalists and those with a religious mindset, which he dates to the fall of Amanullah. In his time, Amanullah had faced two big tribal uprisings from Pashtun tribes led by religious leaders.

Butt sees Abdul Ghaffar Khan as being symptomatic of this rift: until the collapse of Amanullah Khan, Abdul Ghaffar Khan was cooperating with the ulema. Thereafter he pulled his son Ghani out of madrassah education. Khan blamed the ulema for the failure of Amanullah’s reforms.

Any initiative, Butt writes, that does not have the support of the ulema is doomed to fail. It is a lesson Butt states “the next great leader of the Pashtuns” Dr Najib Ullah would experience in seeking to socially transform Afghanistan into a socialist utopia. Butt is silent on the human rights abuses committed by Najib personally and his regime, contributing to millions of dead and displaced – giving rise to a global Afghan diaspora. Many of those who were in jail with Butt in 1974, including the Ustad who taught him Dari, met a bloody fate at the hands of the communists. Whitewashing the deeds of human rights abusers can never be positive.

John had little luck journeying in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In Tirah, he was detained by the Afridis for perceived Wahhabi leanings. While in a guest house/hujra with his Afridi custodians, John Butt may have had reason to think of Molly Ellis, his countrywoman detained by the Afridis in 1923. Later in England, he would meet Molly Ellis, but does not tell us what Ellis made of John’s two incarcerations.

If John had looked further back into history, then In the 19th century, a British soldier had been captured by the Afridis and held prisoner. During the military campaigns of 1897 against the Afridis, the British destroyed most Afridi dwellings and food stocks in a scorched earth campaign.

For those who enjoy good travel writing, Butt’s book can be rewarding. He offers a vision of what people in Pakistan can do. If a foreigner like John Butt can take an interest in Pashto and learn the language, what stops any Pakistani from learning a regional language?

John can read classic poetical works such as those by Rehman Baba. While many of us may read Shakespeare, can we say that we can read Rehman Baba? If we cannot read the poet of the Pakhtuns, are we not the poorer for it?

In the age of the internet, people can aspire to learn many more languages at a much deeper level than was possible in earlier ages.

“‘Who did you hear it from?’ he asked. I told him Faqir Mohammad had called Babji a zalim saray. ‘It means cruel,’ Majeed’s brother replied, clearly not best pleased with Faqir Mohammad, effectively his family’s servant.”

John’s example shows how some effort to learn can pay dividends in picking up fluency in a language.

He embraced Islam in Swat after being touched by the generosity of a fellow traveller on a coach during Ramazan, who bought him some Iftari. John was impressed by the dynamism and confidence of the people of the Swat Valley, who were proud of their values and promoted Islam amongst Westerners who arrived there on the hippie trail. The tradition in Swat was that when a Westerner embraced Islam, they would be paraded down the main bazaar and everyone would offer them gifts of money. Butt tells us of another Briton who converted to Islam in Swat and this convert later established a mosque with mainly British Sufi converts in Norwich.

In 1974, Mr. Butt spent “considerable time in jail in Kabul, in reprisal for the suggested role of the British in the fall of Amir Amanullah himself. It is not history that has become the baggage in Afghanistan, it is people’s false and fanciful notion of history. For Pashtoons, Amanullah has become the hero. For Tajiks, Habibullah Kalakani is the one they look up to. In fact there were both Tajiks and Pashtoons who supported Amanullah in his modernising reforms in the country, just as there were huge and eventually dominant forces of reaction amongst both ethnic groups that either caused or benefitted from Amanullah Khan’s downfall. One only has to look at the edicts issued by Habibullah as king in Kabul. They were remarkably similar to the writ of the Taliban more than six decades later. The only difference was that Habibullah was a Tajik, the Taliban were Pashtoon. The difference is not ideological but ethnic.”

Butt further writes, “If there is a clash of ideas, one can discuss things, come to some accommodation and take things forward. If differences are interpreted as ethnic, then they become fixed, with no give or take. That is what has happened in Afghanistan. In 1974, amongst the nascent progressive, left-wing forces that wrested control in the new government of Daud Khan, the prevalent thinking was that Amanullah Khan had been deposed by an unholy alliance of the British and the mullas. Who better to blame than me: English and a mulla rolled into one?“

Title: A Talib's Tale: The Life and Times of a Pashtoon Englishman

Author: John Butt

Publisher: Kube Publishing Ltd, 2021

“I am indebted to the fast-talking lean-looking Ghulam Rasool. He was serving in the Ministry of Interior when I was taken there from Jalalabad […] He explained to me the reason for the antipathy amongst Afghan progressives to mullas, in particular why they were especially allergic to English mullas, in other words me. .Later others were to give me one famous example […] of a so-called English spy who came to serve in the Pul-e Khisti mosque in the centre of Kabul. I was told how he had led the prayers there for eighteen years. His purpose, so I was told was to topple Amir Amanullah Khan. Once (he) had achieved, in 1929, so the story goes, he returned to Great Britain, famously writing a letter to his congregation that they would have to say their prayers of eighteen years again, since he had been a British spy all along.”

John provides interesting anecdotes on what Afghans thought of their ‘national hero’:

“Amanulah Khan, hailed as a hero by the progressive, nationalist, more secular lobby of Pashtoon society, vilified by the more conservative, religious sections of society is arguably the most divisive figure in modern Afghan history. Progressive Pashtoon nationalists like Ghulam Rasool in the Ministry of Interior glorified him. On the other hand, I heard one maulvi I was in jail with say, probably too loudly for his own good: “Screw the wife of whoever calls him a ghazi (a holy warrior)!”

Butt expresses the view that, “It was in the time of Amanullah Khan that the fault lines emerged in Pashtoon society with progressives on one side, conservatives on the other, Pashtoon society has been grappling unsuccessfully with this division ever since.”

However, it is open to question whether any politician in the region has been ‘progressive’ during the twentieth century since otherwise Pashtun society would not be in the mess it is today.

Butt continues “Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan […] the leading Pashtoon nationalist […] is one who glorifies the role of Amanullah Khan and talks in his book, My Life and Struggle (Zama Jhwand au Jadd o-Jahd), about how the Pashtoons were united in joining their campaign in support of Amanullah Kahn. “There have been many kings of the Afghans he writes but they did not hold any of them so dear as they did Amanullah Khan”. That may have been true of the Pashtoons with whom Ghaffar Khan was associated. However it was also true that a good number of the Pashtoon tribes responded to the cry of their ulema and rose up against Amanullah Khan.”

The author describes a cleavage in Pashtun society between nationalists and those with a religious mindset, which he dates to the fall of Amanullah. In his time, Amanullah had faced two big tribal uprisings from Pashtun tribes led by religious leaders.

Butt sees Abdul Ghaffar Khan as being symptomatic of this rift: until the collapse of Amanullah Khan, Abdul Ghaffar Khan was cooperating with the ulema. Thereafter he pulled his son Ghani out of madrassah education. Khan blamed the ulema for the failure of Amanullah’s reforms.

Any initiative, Butt writes, that does not have the support of the ulema is doomed to fail. It is a lesson Butt states “the next great leader of the Pashtuns” Dr Najib Ullah would experience in seeking to socially transform Afghanistan into a socialist utopia. Butt is silent on the human rights abuses committed by Najib personally and his regime, contributing to millions of dead and displaced – giving rise to a global Afghan diaspora. Many of those who were in jail with Butt in 1974, including the Ustad who taught him Dari, met a bloody fate at the hands of the communists. Whitewashing the deeds of human rights abusers can never be positive.

John had little luck journeying in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In Tirah, he was detained by the Afridis for perceived Wahhabi leanings. While in a guest house/hujra with his Afridi custodians, John Butt may have had reason to think of Molly Ellis, his countrywoman detained by the Afridis in 1923. Later in England, he would meet Molly Ellis, but does not tell us what Ellis made of John’s two incarcerations.

If John had looked further back into history, then In the 19th century, a British soldier had been captured by the Afridis and held prisoner. During the military campaigns of 1897 against the Afridis, the British destroyed most Afridi dwellings and food stocks in a scorched earth campaign.

For those who enjoy good travel writing, Butt’s book can be rewarding. He offers a vision of what people in Pakistan can do. If a foreigner like John Butt can take an interest in Pashto and learn the language, what stops any Pakistani from learning a regional language?

John can read classic poetical works such as those by Rehman Baba. While many of us may read Shakespeare, can we say that we can read Rehman Baba? If we cannot read the poet of the Pakhtuns, are we not the poorer for it?

In the age of the internet, people can aspire to learn many more languages at a much deeper level than was possible in earlier ages.